A Cruel and Shocking Act: The Secret History of the Kennedy Assassination (37 page)

Read A Cruel and Shocking Act: The Secret History of the Kennedy Assassination Online

Authors: Philip Shenon

Belin had always known how to satisfy an audience. Raised in a music-loving home in Sioux City, he was a violin prodigy who was so talented that he won admission to New York’s Juilliard School of Music. His family had little money, however, and he bypassed Juilliard to join the army; he planned to take advantage of the GI Bill to pay for college later. He brought his violin with him and performed at military hospitals in the Far East and on armed forces radio; for the radio performances, he always preferred compositions by Dvořák, which he thought he played particularly well.

Another letter to Des Moines followed on February 11. As an Iowan, he mocked the inability of the city government in Washington to plow the streets after what was, by the standards of the Hawkeye State, a mild dusting: “Washington is completely disorganized today, for overnight there has been three inches of snow.” He then went on to share details of the recent closed-door testimony by Oswald’s mother. “One of the more cynical of the lawyers here has suggested that Marguerite be nominated for ‘Mother of the Year’ in light of her great protestations in defense of her offspring,” he wrote, adding that Warren had demonstrated remarkable patience in sitting and listening to her babble. “If some of us had gambling instincts, which of course I do not, we would start a pool in an effort to determine how long the Chief Justice will sit back and listen to all of the irrelevancies that are coming forth.”

*

By late winter, Belin had read through most of the hundreds of witness statements gathered in Dallas by the FBI, the Secret Service, and the Dallas police. He had never worked in law enforcement, but he had plenty of experience in cross-examining witnesses, and he insisted to colleagues on the commission’s staff that he was not worried about the many discrepancies he noted in the witness accounts of what had happened at Dealey Plaza and at the scene of the murder of Officer J. D. Tippit. Discrepancies among important, well-meaning witnesses were common in the civil cases he handled back in Des Moines, and so it was here. “When there are two or more witnesses to a sudden event, you will always get at least two different stories about what happened.”

Some of the discrepancies from Dallas were almost funny. For instance, Oswald’s fellow workers at the book depository—although clearly trying to testify honestly—could not agree on even the most basic details about his appearance. Asked how Oswald dressed, one coworker, James Jarman Jr., swore that he always wore a T-shirt. Another, Eugene West, said exactly the opposite: “I don’t believe I ever seen him working in just a T-shirt.” Belin thought both men were telling what they believed was the truth, even if one of them had to be wrong. There were far more jarring discrepancies elsewhere, especially in the witness statements of the two Secret Service agents who were in the president’s limousine in Dallas. Agent Roy Kellerman, who was riding in the front passenger seat, insisted that after the first shot, he heard Kennedy yell out, “My God, I am shot!” Kellerman was asked how he could be so certain it was Kennedy, not Connally, who shouted. “It was his voice,” Kellerman said. “There is only one man in that backseat that was from Boston, and his accent carried very clearly.”

Yet the agent who was driving the limousine, William Greer, insisted that Kennedy said nothing after the first shot. Connally and his wife, Nellie, also in the limousine, agreed with Greer: the president remained silent. (The commission’s staff determined that Greer and the Connallys were almost certainly right, since the first bullet passed through Kennedy’s voice box, making it impossible for him to say anything.) Yet while their accounts were completely contradictory, Belin asked, would anyone suggest that either Kellerman or Greer was lying?

Belin’s letters to his colleagues became more somber in March, when he and Ball made their first trip to Dallas. They saw Dealey Plaza for themselves and drove the length of the route of Kennedy’s motorcade. “I really was not prepared for the emotional experience of actually seeing the building for the first time,” Belin wrote, adding:

With a Secret Service man at the wheel, we drove the presidential parade route down Main Street in Dallas and followed it directly to Houston Street where the car turned to the right and there, one block ahead, standing in stark reality, was the TSBD Building, about which I had read so much over the past sixty days. In a matter of seconds, I put myself in the actual parade procession with the colored moving pictures that we actually have that were taken on the day of the assassination. The car drove slowly north on Houston Street one block to its intersection with Elm, and my eyes froze on the window at the southeast corner of the sixth floor. We turned to the left—a reflex angle of about 270 degrees, and we started down the diagonal entrance into the Expressway. This is where the shots struck the president.

It was at that moment, Belin wrote, that his mind was overcome with a “flash” of memories of the grisly evidence he had reviewed back in Washington—the autopsy report, the Zapruder film, the photographs of the bullet fragments and of bits of the president’s skull found in Dealey Plaza.

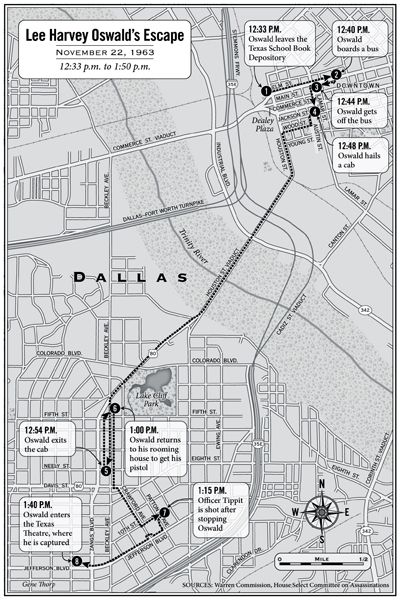

While in Dallas, Belin retraced what the FBI believed was Oswald’s journey, by taxi and then by foot, after the assassination—first, to his rooming house in the Oak Cliff neighborhood, and then to the scene of the murder of Officer J. D. Tippit. Belin thought it was cruel that Tippit’s name and his murder were often forgotten in discussions of the assassination, as if the policeman’s death had been an insignificant footnote to the events of that day. Friends on the police force described the thirty-nine-year-old Tippit—he told friends his initials, “J.D.,” stood for nothing in particular—as a fine man. An army paratrooper in World War II, he had participated in the Allied crossing of the Rhine in 1945 and earned a Bronze Star. In 1952, he was hired by the Dallas police as a $250-a-month apprentice. He left behind a wife and three children, the youngest of them five years old.

Belin thought the evidence that Oswald had killed Tippit was incontrovertible. Driving in his patrol car, the officer had noticed Oswald walking on the side of the road; Tippit tried to stop and question him, thinking he matched the description of the president’s assassin that had just been broadcast on the police radio. As he stepped from his car, Tippit was hit by four bullets—three in his chest, one in his head—and cartridge cases found at the scene were a precise match for Oswald’s Smith & Wesson pistol, purchased from the same Chicago mail-order house that sold him the Mannlicher-Carcano rifle.

As part of his tour, Belin also visited the Texas Theatre (its owners preferred the European spelling of “theatre”) on West Jefferson Boulevard, a few blocks away from the scene of Tippit’s murder. Oswald had been arrested in the movie house—initially for Tippit’s murder, not the president’s—after he ducked past the ticket booth without paying and tried to hide in the darkened audience. Belin told his colleagues back in Iowa that he made a special point of plopping himself down “in the seat where Oswald was apprehended.”

Belin and Ball set aside hours to inspect the book depository and interview Oswald’s coworkers, including three men who said they had been on the fifth floor of the building, watching out the window as Kennedy’s motorcade passed by, when the shots rang out. The coworkers agreed in earlier police interviews that they had heard the bolt of a rifle moving back and forth just above them; they also said they had heard the sound of empty cartridge cases hitting the floor. Belin wanted to test out whether that could be true. The warehouse had cement floors that were thick enough to bear the weight of tons of school textbooks, and Belin wondered if it would really be possible for someone a floor below to make out the relatively subtle sound of a rifle bolt and of cartridges striking the floor above. Perhaps, he thought, Oswald’s coworkers had imagined what they said they heard.

For the test, Belin and Ball placed a Secret Service agent with a bolt-action rifle on the sixth floor, at the southeast corner window where Oswald had been seen. Ball stayed with the agent while Belin went downstairs to the fifth floor with Harold Norman, one of the depository employees. “I then yelled for the test to begin,” Belin wrote later. “I really did not expect to hear anything. Then, with remarkable clarity, I could hear the thump as a cartridge case hit the floor. There were two more thumps as the two other cartridge cases hit the floor above me.” He said he could also hear the Secret Service agent move “the bolt of the rifle back and forth—and this too could be heard with clarity.”

“Joe, if I had not heard it myself, I would never have believed it,” Belin told Ball.

Belin conducted another test designed to see how quickly Oswald could have gotten from the sixth floor to the second floor, where Oswald had encountered his supervisor, Roy Truly, and Dallas police officer Marrion Baker within seconds of the shots. Baker said he had stopped his motorcycle and run into the building when he heard the gunfire because he believed it had come from the book depository. Belin ran behind Baker with a stopwatch as Baker re-created his movements, jumping again from his motorcycle outside the depository and then rushing in and climbing to the second floor. The test left Belin panting for breath. (In joining the commission, “no one told me that there would be physical exertion involved,” he joked to his friends in Iowa.) The test proved to Belin that Oswald had the time to descend to the second floor before the police officer arrived there.

Belin was surprised that he was the first investigator to conduct these tests. For all their claims of an exhaustive investigation in Dallas, the FBI, the Secret Service, and Texas authorities had left gaping holes in the record. He was astonished to come across an important witness who had been all but ignored by other investigators: Domingo Benavides, an auto repairman who stopped his 1958 Chevy pickup when he saw Tippit gunned down near the corner of Tenth and Patton Streets. “I could hardly believe what the man was telling me,” Belin said. Benavides said he had not only witnessed the policeman’s murder, he had then gone to Tippit’s car and tried desperately “to use the police radio to tell the department that an officer had been shot.” He found two empty cartridge shells that the man he identified as Oswald had thrown into the bushes, and he turned them over to police.

Yet while Belin had managed to track down Benavides easily enough, his name did not appear in any of the witness statements prepared by the FBI and the Dallas police on the day of the assassination. The police had not bothered to take Benavides to police headquarters on the afternoon of Tippit’s murder to identify Oswald, as they did with other witnesses. Why, Belin asked, was it being left to the commission to discover such a critical witness?

*

After the Dallas trip, Belin returned to Washington to begin taking formal, sworn testimony from some of the same witnesses he had met in Texas. Among them was the man he considered to be “the single most important witness” at Dealey Plaza—Howard Brennan, the forty-four-year-old steamfitter who had been sitting on a wall at the corner of Houston and Elm Street, directly across the street from the book depository, when the shots rang out. Brennan’s spot on the wall was only about 110 feet from the sixth-floor window. Other, highly credible witnesses said they saw a rifle pointing out of one of the upper windows, including a photographer for the

Dallas Times-Herald

who was riding in the motorcade and who, after hearing the first shot, pointed up and yelled out to his colleagues, “There is the gun!” Brennan, however, provided by far the most detailed account, including a clear physical description of the shooter. In the minutes before the shots, he said, he had looked up at the windows of the book depository and “observed quite a few people in different windows” who seemed to be eagerly awaiting the chance to see the president. “In particular, I saw this one man on the sixth floor.”

A moment after the president’s limousine passed by, Brennan said, “I heard this crack that I positively thought was a backfire”—from a motorcycle engine, he thought. Then, Brennan said, he heard a second noise that sounded like a firecracker being thrown from the book depository. “I glanced up. And this man—that I saw previously—was aiming for his last shot.” The man held “some type of a high-powered rifle” and was “resting against the left window sill, with the gun to his right shoulder, holding the gun with his left hand and taking positive aim and fired his last shot.” That was the third shot, the one that hit the president in the head, Brennan said. The assassin, Brennan said, was white, about 160 to 170 pounds and wearing light-colored clothes—a reasonably accurate description of Oswald. In the chaos after the shots, Brennan approached police officers and told them what he had seen. Minutes later, police radios across town crackled with the department’s description of the gunman, apparently based on Brennan’s account.

That afternoon, a shaken Brennan was taken to police headquarters and shown a lineup that included Oswald. At that instant, Brennan admitted later, he made a decision to lie. Although he later said he knew the president’s assassin was standing right in front of him, he looked over the lineup and claimed he could not pick out the gunman. He lied, he said later, because he feared that Kennedy had been killed as part of a foreign conspiracy—“a Communist activity”—and that he might be next to die. “If it got to be a known fact that I was an eyewitness, my family or I, either one, might not be safe.”