A Cruel and Shocking Act: The Secret History of the Kennedy Assassination (60 page)

Read A Cruel and Shocking Act: The Secret History of the Kennedy Assassination Online

Authors: Philip Shenon

*

Marina Oswald returned to the commission’s offices on Thursday, June 11. This time, there was no statement from Warren to welcome her or to express gratitude for her testimony. There was no grandfatherly concern for her welfare and that of her children. The questioning, led by Rankin, often bordered on hostile.

Rankin: “Mrs. Oswald, we would like to have you tell about the incident in regard to Mr. Nixon.”

Marina seemed to understand how much trouble she was in. “I am very sorry I didn’t mention this before,” she began, speaking through a Russian translator. “I had forgotten entirely about the incident with Vice President Nixon when I was here the first time. I wasn’t trying to deceive you.”

Ford pressed her: “Can you tell us why you didn’t mention this incident?”

Marina: “I was very tired and felt that I had told everything.”

She then offered what she said was the full story about the Nixon threat—how in mid-April 1963, several days after her husband’s assassination attempt on Walker, Oswald told her that he was about to go to the street in search of Richard Nixon. Oswald, she said, claimed that Nixon was visiting Dallas that day. He grabbed the pistol he kept in the house and said, “I will go out and have a look and perhaps I won’t use my gun. But if there is a convenient opportunity, perhaps I will.” She said she was terrified by the threat and attempted to lock her husband in the bathroom to prevent him from leaving. “We actually struggled for several minutes and then he quieted down,” she said. “I remember that I told him that if he goes out, it would be better for him to kill me.”

Even as she tried to explain away the gaps in her earlier testimony, Marina was creating new confusion, especially since the commission’s staff determined that Nixon did not visit Dallas in April 1963. Some of the commissioners questioned whether she was confusing former vice president Nixon with then vice president Lyndon Johnson, who had been in Dallas that month. She was certain she was not confused, however. “I remember distinctly the name Nixon,” she said. “I never heard of Johnson before he became president.”

Allen Dulles put the question to her: If her husband had tried to kill Walker and threatened to kill Nixon, “didn’t it occur to you then that there was danger that he would use these weapons against someone else? He never made any statement against President Kennedy?”

“Never,” she replied. “He always had a favorable feeling about President Kennedy.”

She made a new plea for the commission’s sympathy. She tried to explain away her failure to warn the police—or anyone else—that her husband was capable of political violence. She had remained silent, she said, because she had been terrified that her husband might someday be arrested and jailed, abandoning her in a country in which she had no family and few friends. She wanted to remain in the United States and worried that she might be deported to Russia if she turned her husband in. “Lee was the only person who was supporting me,” she said. “I didn’t have any friends, I didn’t speak any English and I couldn’t work and I didn’t know what would happen if they locked him up.”

Her husband had been taunting her for months with the possibility that she would be forced to return to Russia without him, she said. He had a “sadistic” streak and made her “write letters to the Russian embassy stating that I wanted to go back to Russia,” she said. “He liked to tease me and torment me in this way.… He made me several times write such letters.” Over her protests, he then mailed the letters. She said she had resigned herself to the possibility of a bleak return to her homeland. “I mean if my husband didn’t want me to live with him any longer and wanted me to go back, I would go back,” she said. “I didn’t have any choice.”

*

By Thursday, July 2, the date of Mark Lane’s second and final appearance before the commission, he was as well known to the American public as most of the commissioners. At the age of thirty-seven, Lane was now a celebrity, with admirers around the world eager to hear him explain how Lee Harvey Oswald had been framed and how the chief justice was covering up the truth. When the commission forced Lane to return to Washington under threat of a subpoena, he had to cut short a tour of Europe, where he was giving speeches and raising money.

The commission’s stated reason for calling him to testify a second time was to demand that he reveal the source of some of his more shocking allegations, especially his claim of a meeting in Ruby’s Carousel Club a week before the assassination that was attended by Officer J. D. Tippit and a prominent anti-Kennedy activist. The commission’s staff had found nothing to back up the rumor, nor had any of the reporters in Dallas who had all heard it from the same drunken Texas lawyer who had been peddling the story for months. The commission was also still trying to resolve the confusion over Lane’s claim that Dallas waitress Helen Markham, one of the witnesses to Tippit’s murder, had backed away from her identification of Oswald as the killer.

After taking his seat at the witness table, Lane wasted no time: he made it clear that he would answer none of the commission’s central questions and declared that there was no way to force him to.

Warren appeared to struggle to contain his anger. Unless Lane offered up his sources, “we have every reason to doubt the truthfulness of what you have heretofore told us,” the chief justice told Lane, effectively accusing the young lawyer of perjury. Lane felt free to conduct his own “inquisition” into the assassination and repeat any outrageous rumor he came across, Warren said. “You have done nothing but handicap us.”

Lane was defiant: “I have not said anything in public, Mr. Chief Justice, that I have not said first before this commission.… When I speak before an audience, I do hold myself out to be telling the truth, just as when I have testified before this commission, I have also told the truth.” With Lane, the commission would get no further.

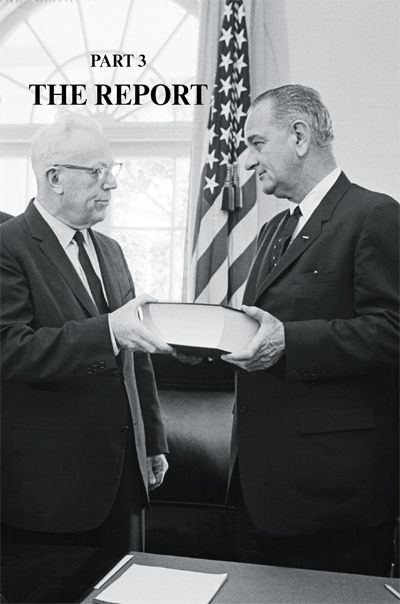

Chief Justice Warren delivers the commission’s report to President Johnson, September 24, 1964

44

THE HOME OF EARL AND NINA WARREN

SHERATON PARK HOTEL

WASHINGTON, DC

JUNE 1964

Warren’s devoted wife, Nina, worried most of all. She said that the chief justice, who had turned seventy-three in March, was working so hard that he had put his health at risk. Through the spring, the commission’s work had soaked up every free minute of his day and night away from the court. Late each evening, before sleeping, he sat up in bed and tried to make his way through a growing stack of transcripts of the testimony of recent witnesses before the commission.

In the decade since he had arrived in Washington, Warren tried to stay in good shape. He liked to swim for exercise. Drew Pearson thought the beefy, white-haired chief justice resembled an aging but contented sea lion as he glided through the water. For most of 1964, though, Warren had to give up his late-afternoon visits to the pool at Washington’s University Club; there was simply no time. “The Warren Commission was a drag on him,” said Bart Cavanaugh, the former city manager of Sacramento, California, and one of Warren’s closest friends. “It was an awful strain.” Cavanaugh visited the Warrens in Washington that spring. “Mrs. Warren said he was awfully worn down, that he’d lost considerable weight.” She urged Cavanaugh to help take her husband’s mind off his work by getting him out of town. “Mrs. Warren said, ‘Why don’t the two of you sneak off and go to New York for the weekend?’ and we did,” Cavanaugh said. “We drove up to New York, went to the ball game.” But the next week, back in Washington, the pressure of Warren’s two full-time jobs returned.

His aggravation rose as each of the deadlines he set for the commission’s work slipped. He had begun to worry that he would not get any summer vacation at all that year. As of early June, only the ever-efficient Arlen Specter—operating without help or hindrance from his long-departed senior partner, Francis Adams—had finished a draft of his portion of the report, outlining the events of the day of the assassination. Most of the other teams had known for weeks that the deadlines were hopeless.

The chief justice had stopped hiding his anger over the delays. Slawson remembered Warren’s fury when his initial June deadlines were not met. On May 29, the last Friday in May, Rankin realized that Warren would have to be told, once and for all, that the staff would fail to meet the deadline the following Monday—June 1—for completing draft chapters of the report. As Rankin prepared to go home for the weekend, he asked Willens to break the news: “You had better tell the chief it won’t be ready.” The chief justice was “furious,” Slawson recalled. Willens said he thought Warren’s anger was understandable. For most of his life, after all, the chief justice had controlled his own schedule, as well as the schedule of the people who worked for him. Now, his schedule was at the mercy of a group of young lawyers, most of whom he barely knew. He felt he was “a prisoner of the staff,” Willens said.

Warren, who normally escaped Washington every July and August to avoid the capital’s swamp-like heat, shortened his vacation to a month. He planned to leave on July 2 to go fishing in his beloved Norway, his family’s ancestral home, and to return in early August, in time to oversee the final writing of the report. Before departing, he got around to answering some of the scolding letters he had been receiving all year from prominent lawyers around the country who wanted to tell him how wrong he had been to accept the job of running the commission. In his belated replies, Warren told his critics that they were right and that he had taken the assignment only because President Johnson insisted. “I share your view that it is not the business of members of the Court to accept outside assignments,” Warren wrote to Carl Shipley, a Washington securities lawyer. “I had expressed myself both in and out of Court circles to that effect.” In explaining why he had taken the job, Warren cited a favorite quotation from President Grover Cleveland: “Sometimes, as you know, we are faced with—as Grover Cleveland said—a condition and not a theory. In this situation, the President so impressed me with the gravity of the situation at the moment that I felt in good conscience I could not refuse.”

The Supreme Court had just completed another eventful term, with the justices deciding several landmark cases, including

New York Times v. Sullivan

, a unanimous decision announced in March in which the court struck a blow for both free speech and civil rights. The ruling weakened the ability of public officials to use libel laws to punish journalists; at the time, the laws were being used to bankrupt news organizations reporting on civil rights abuses in the South. On June 22, in

Escobedo v. Illinois

, the court held that criminal suspects had a right to counsel during police interrogations—an extension of the protections granted to criminal defendants in the unanimous

Gideon v. Wainwright

decision the year before. Unlike the Sullivan and Gideon cases, Escobedo had been a close call: the ruling had a bare 5-4 majority. The one-vote margin suggested to some lawyers that Warren’s campaign to expand the rights of criminal defendants was losing momentum.

Warren said later that he had always understood it would be difficult to achieve unanimity on the commission—to bridge differences among seven men who, in other circumstances, would agree on almost nothing. “Politically, we had as many opposites as the number of people would permit,” he recalled. “I am sure that I was anathema to Senator Russell because of the court’s racial decisions.” He was struck by how much hostility there was between Democratic congressman Boggs and Republican congressman Ford: “They were not congenial—there was no camaraderie between them.” The chief justice had much more respect for Boggs than for Ford, even if Boggs was far less active in the investigation. “Boggs was a good commissioner,” the chief justice said. “He approached things objectively. I found him very helpful.” Boggs also had the nicer disposition, he thought. “Boggs was friendly and Ford was antagonistic.” Warren said he came to have great respect for the common sense of John McCloy, who seemed always to rise above partisanship. “He was objective and extremely helpful.” And despite Allen Dulles’s eccentricity and tendency to nap during meetings, he was “also very helpful … he was a little bit garrulous, but he worked hard and was a good member.”

By late spring, Warren thought he had won over most of the commissioners to his conviction that Oswald acted alone. “The non-conspiracy theory was probably the basic decision of the case.” The most outspoken holdout, he said, was Ford, who continued to suggest the possibility that Oswald had been part of a conspiracy, probably somehow involving Cuba. “Ford wanted to go off on a tangent following a Communist plot,” Warren remembered. He also could not be sure where Russell would come out, given how little the senator had been involved in the investigation.

*

The work of drafting the report was left almost entirely to the staff, which was typical for a federal blue-ribbon commission. Warren and the commissioners decided they would weigh in after they were presented with draft chapters. As he had long planned, Redlich, now secure in his job thanks to the chief justice, assumed the role of the report’s central editor, working with Willens and Alfred Goldberg. Rankin reserved for himself the final decisions about the editing, at least until the drafts reached the commissioners. His goal, he said, was to edit the report for a uniform, sober style and to stick as much as possible to the facts of the case against Oswald, without overstating them. “I wanted everything to be as precise as possible,” he recalled. Staff members who wanted to complain about the way their chapters had been rewritten would automatically be granted an audience, Rankin announced.