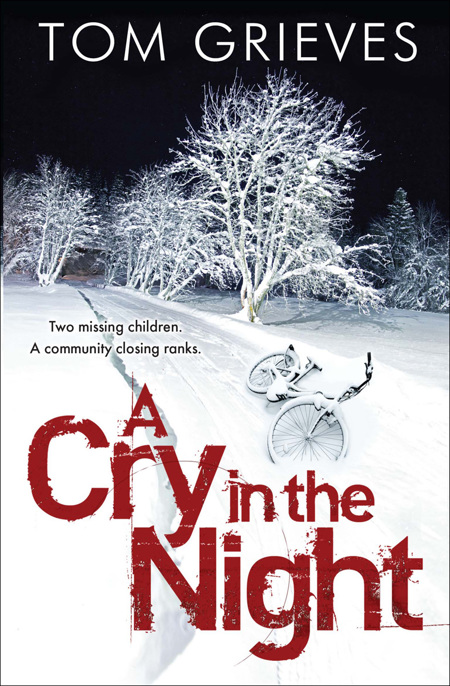

A Cry in the Night

Read A Cry in the Night Online

Authors: Tom Grieves

First published in Great Britain in year of 2014 by

Quercus Editions Ltd

55 Baker Street

7th Floor, South Block

London

W1U 8EW

Copyright © 2014 Tom Grieves

The moral right of Tom Grieves to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 85738 985 5

Ebook ISBN 978 0 85738 986 2

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organisations, places and events are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

You can find this and many other great books at:

www.quercusbooks.co.uk

Also by Tom Grieves

Sleepwalkers

Tom Grieves has worked in television as a script editor, producer and executive producer, as well as a writer.

A Cry in the Night

is his second novel. Tom lives in Sussex with his wife and three sons.

This is for my parents, John and Ann, who would take me and my sister to the Lake District every Easter. This book grew out of every peak we climbed, every rainstorm we survived and every last corner of Kendal mint cake over which we fought.

Although the water is cold and clear, it still has its secrets. The pebbles in the shallows are easy to see, but beyond, a good mile from land where the wind buffets the surface, the water is so deep that the view below is impenetrable. From here, looking up and back at the shore, the steep fells rise majestically into tumbling clouds. Chunky rocks spew out from the slopes like angry welts, sheep dot the fields, and ancient stone walls cut and divide the land. The view remains unchanged over centuries.

It was the same sight that greeted the small village of Lullingdale in 1604. Its inhabitants were honest, God-fearing men and women who made their meagre living off the land. Among them was a pretty young girl called Catherine Adams. Catherine was the eldest daughter of seven and had inevitably grown up quickly. Her status as the eldest had led to her helping with children and then to midwifery. This began when she was only nine years old, and

she soon became something of a good luck charm. Margaret Gifford, the skinner’s wife, swore that she would never have survived the birth of her first were it not for Catherine, and, remarkably, no baby had ever died under her watch. Catherine would blush and stammer when praised, and it certainly wasn’t her who mentioned miracles. But the word was used nonetheless and, in time, carried over the fells and across rivers until it reached the court of King James I.

King James was also a God-fearing man. Having survived a plot to kill him by some three hundred witches in 1590, he was determined to rid the country of their curse. This determination became an obsession, and the monarch was soon an expert on the subject. Witches, he decided, danced with the devil, and where one was discovered, more would be found. He also decreed that it was possible to discover them in actions that might initially seem benign. The act of healing might not be what it seemed. Nor, it could be assumed, might the ability to deliver babies without ever suffering an accident or stillbirth.

Catherine Adams would shrug bashfully when reminded of her feats. She had no idea that her good fortune and skill would speed John Stern into the village, with his team of men who watched her and every woman with mistrust.

Until John arrived, it had been thought inevitable that Catherine would marry the bashful shepherd Robert Cox. The village would have celebrated their union with a single,

delighted voice. But John Stern was not fooled by a sweet disposition. Once he had set his eye on Catherine, it was only a matter of time before he exposed her.

Catherine was stripped naked, and although no mark of the devil was found on her, John Stern was undeterred. Witches, he told the cowed villagers, were cunning and deceitful. He then used his pricking stick, poking young Catherine in the back without warning. She did not react at first, and John claimed that this inability to feel pain was proof of her wickedness. Her fate was sealed.

The girl was dragged away, condemned as guilty. Now she was important only for one thing – to find and expose the others. John served the King and did God’s work. He beseeched the villagers to help him exorcise this evil and save their souls from the danger that swirled invisibly around them.

Perhaps Catherine had danced too gaily at the May Fayre. Had her mother not been so distracted with her wayward brothers, she might have warned Catherine not to laugh so easily with the men. And had she been less pretty, then perhaps the villagers might not have let John drag her away.

The next morning, the mud-stained, beaten and bloodied figure was paraded in chains before the village. She was a harlot, a witch, a partner of the devil, and she had betrayed them all. It is not clear whether it was Catherine who mentioned Lucy Darwent’s name or whether John had seen the girl staring at him, but his finger pointed to her. No one

stopped his men from throwing her to the ground, ripping her skirt up to her waist and declaring that the mole on her thigh was the mark of the devil. Angry and fearful, she spat in John Stern’s face and screamed at the men as they shaved her head, cutting her scalp and breaking her teeth. Only minutes before, she had been rather beautiful, but in their arms she was branded dangerous, and her appearance proved their words.

A herd of sheep had died earlier that spring, and at the time it was blamed on bad fortune and the shepherd’s foolhardiness – letting them graze too high on the fells when the weather was still so bitter. But now, with John’s expert eye on matters, it became clear that the animals’ deaths were a result of curses and spells. And the only woman who could have put such a hex on so many animals was Elinor Sibbell, a hunchbacked grandmother who had never spent a single day outside of the village. Elinor’s age and physical weakness earned her no favours with John’s men, and she was bound and broken with the others.

When he had six, John was satisfied. Some might say that his work proved unprofitable until he reached this number, but their voices are not recorded. Instead, John was able to rely on the fear of the male villagers, desperate to rid themselves of the wickedness among them, angry that they had not seen it themselves, fearful that their inability to spot it might turn eyes onto them.

It is unclear what happened that night. The witches were taken away to a hut at the edge of the village where they confessed their wrongdoing and repented of their sins. The husbands were told that they were not at fault. The devil was to blame and all that the men could do was pray to God that he would deliver them from the women’s black hearts. The men took comfort from John’s words. They agreed that a woman’s guile was like no other and swore that they would not be fooled again. They retired in each other’s company and felt safer for it. Perhaps it was the darkness that made this possible. Ghost, ghouls and gremlins are easily conjured against the eternal black canvas of a starless night.

The next morning, the witches were paraded before the village. They were spat at and cursed as brave John Stern delighted the crowd by announcing their confessions. They had admitted to the murder of farmer Francis Clifford’s prize bull, which everyone had previously assumed to have died of old age. They had confessed to dancing naked with the devil by firelight near the lake while the menfolk slept, and admitted to future plans of evil. John Stern was good at his job and he controlled his crowd with the skills of a master showman. No one, it seemed, noticed that the women remained silent. But who would deny the words of good John Stern, servant of King James I and the Lord God Almighty?

Seven-year-old William Henshaw was only too happy to offer up his father’s boat for the final proof and purification of the witches. The villagers came to watch as John and two of his men rowed the women out on the water. And there, with their hands tied behind their backs and their legs in hastily made shackles, the witches were thrown into the lake. All sank without a trace. This, good John said, was proof that their sins were finally purged. Had they floated and survived, then the devil’s powers still flowed unabated through their hearts. The silence of the water was proof that good had won out. The witches were gone. The village was once again safe and John Stern could leave them to continue lives of prosperity and obedience.

While John Stern had stood among them on the land, the men had cheered with an impassioned zeal. Even the usually taciturn William Cox had shouted and spat against fair Catherine. But watching the action unfold out on the lake, the crowd’s fervour faded. As the women plunged into the water, the men’s voices were replaced with the tremulous wail of sisters, mothers and daughters who mourned their own with powerless, desolate grief. The men could not look at them.