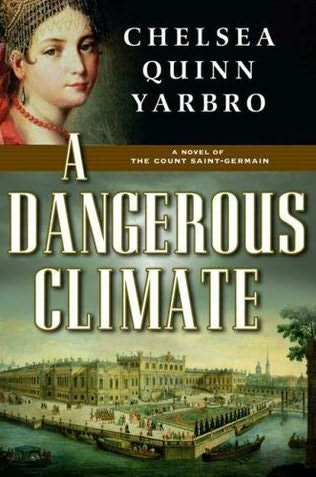

A Dangerous Climate

Read A Dangerous Climate Online

Authors: Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

Tags: #Fiction, #Horror, #Fantasy, #Historical, #Dark Fantasy

By Chelsea Quinn Yarbro from Tom Doherty Associates

Ariosto

Better in the Dark

Blood Games

Blood Roses

Borne in Blood

A Candle for D'Artagnan

Come Twilight

Communion Blood

Crusader's Torch

A Dangerous Climate

Dark of the Sun

Darker Jewels

A Feast in Exile

A Flame in Byzantium

Hotel Transylvania

Mansions of Darkness

Out of the House of Life

The Palace

Path of the Eclipse

Roman Dusk

States of Grace

Writ in Blood

DANGEROUS

CLIMATE

N

OVEL OF THE

C

OUNT

S

AINT-

G

ERMAIN

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously.

A DANGEROUS CLIMATE

Copyright (c) 2008 by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

All rights reserved.

A Tor Book

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, LLC

175 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10010

[http://www.tor-forge.com] www.tor-forge.com

Tor(r) is a registered trademark of Tom Doherty Associates, LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

First Edition: October 2008

Printed in the United States of America

0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For

Gaye Raymond

Author's Notes

terem,

the women's quarters where children were raised, he was active; he much preferred his time in the country, where he organized his friends into a kind of semi-military, semi-courtly group, which later not only formed the heart of the Russian army, it also provided many of his closest advisors. Known as the

poteshnye

(meaning roughly those with whom one is entertained/has adventures), they were as crucial to Piotyr's achievements as any single factor in his life.

provided the labor force for the first year of city-making, a number that in time increased to 150,000, or as high a number as 200,000 by some estimates. Criminals were sent by the thousands to do the grueling work of draining the marshes and building first wooden and then stone embankments to shore up the banks of the Neva River, as well as to sink piles into the boggy soil to provide a foundation for the buildings to come. The first year, 1703--04, deaths among laborers were high: living in the open with bad water and poor food, occasional outbreaks of Swamp Fever (probably caused by giardia) as well as typhus, two epidemics of influenza, and a persistent form of what seemed to have been ringworm, to say nothing of accidents on the job and raids by outlaw gangs, soon reduced the number of laborers by as much as 15 percent. Yet the work went on, and more workers arrived to augment the forces already there. Within two years, more conscripted laborers were put to the task of planting trees and turning the wooden walkways into stone sidewalks and paved streets. Piotyr was determined to create a Baltic Amsterdam, another symbol of Russia's becoming part of Europe. During these first five years, Piotyr summoned many European diplomats as well as engineers and architects to Sankt Piterburkh; many interested governments sent residents and envoys to the new city in order to keep an eye on what was going on. As workers strove to put up houses and barracks to the Czar's order for accommodation of the newcomers, foreign residents came in ever-increasing numbers to the newly founded city. In conditions that resembled a survival camp in a construction zone, these foreigners were expected to carry on as if they were at court at Versailles or Berlin, making for difficult social conditions for everyone, though Piotyr saw it as a validation of his European ambitions for Russia.

have been impossible had he not been an absolute monarch. But that didn't mean he was all affability and progress; from time to time he succumbed to severe panic attacks, during which he would flee any perceived danger. In addition to these occasional outbursts of cowardice, he had a fearsome temper and in his rages was known to wreck whole houses. While in the throes of these episodes only his second wife, Ekaterina, could deal with him--everyone else was too terrified to approach him. She had been his mistress for many years before they married, a Livonian orphan named Martha or Marfa Skavronskaya, who took the name Ekaterina at her wedding and official conversion to the Russian Orthodox faith. Eventually Martha/Marfa/Ekaterina and Piotyr had twelve children, only two of whom--both daughters--survived beyond childhood.

expanded the number of foreigners in his new city by hiring additional architects from Italy; teachers from Holland, Switzerland, and Austria; artists from France and Italy; anatomists from Holland, Switzerland, and Italy; city designers (civil engineers) from Scotland and Ireland; structural engineers from Scotland, Ireland, and Holland; shipbuilders from Holland, Denmark, and England; and musicians from all over. He also encouraged the foreign diplomats to bring accomplished men with them--at their own expense, of course--to help in creating Sankt Piterburkh. The rest of the city gained much of its Russian population from Piotyr's orders personally issued to merchants, artists, writers, artisans of all sorts, bankers, mercers, horticulturalists, builders, and others he deemed necessary to create the new city, compelling them to move to Sankt Piterburkh and to remain there until such time as he would release them. To refuse was tantamount to treason, and leaving the city could only be done by securing the written permission of the Czar.