A Deeper Blue (27 page)

Townes, Jeanene, and Will Van Zandt, 1983.

PHOTO BY JIM MCGUIRE, COURTESY OF NASHVILLEPORTRAITS.COM.

Townes with Royann and Jim Calvin at the Old Quarter, Galveston,

Texas, 1996.

COURTESY OF ROYANN CALVIN.

Claudia Winterer, Nashville,

Tennessee, 1996.

COURTESY OF ROYANN CALVIN.

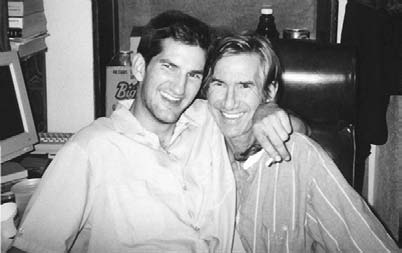

Father and son: Townes and J.T., back room, Cactus Café, Austin,

Texas, 1996.

COURTESY OF ROYANN CALVIN.

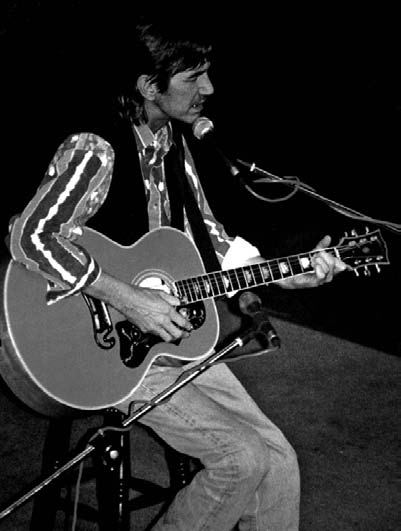

Townes performing in Glasgow, Scotland, 1995.

COURTESY OF THE PHOTOGRAPHER, GRAHAM STEWART.

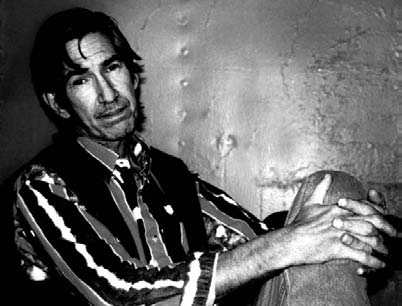

Backstage, Glasgow, Scotland, 1995.

COURTESY OF THE PHOTOGRAPHER, GRAHAM STEWART.

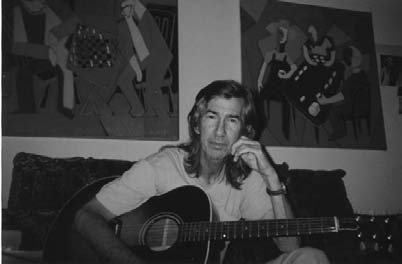

Townes with guitar and Bo Whitt paintings at Rex Bell’s house near

Galveston, Texas, 1996.

COURTESY OF ROYANN CALVIN.

12

Still Lookin’ For You

A

S VAN ZANDTTOUREDTHEclub circuit throughout 1979, he repeatedly circled back to his old stomping grounds in Houston and Austin, where he revived some old friendships and fell into some new business relationships. John Cheatham had been part of the Clarksville scene a few years before, and Townes often stayed at his house in north Austin when he was in town. At some point, they decided that it would be mutually advantageous for Cheatham—who had some funding and an entrepreneurial bent—to take on some management duties for Townes, at least as far as getting some bookings in Texas.

Townes had grown distant from Lamar Fike, and from Kevin Eggers, often informally landing gigs on his own, especially in Texas. “I don’t think he had a clue what to do,” John Lomax says of Cheatham, “but the vibe was good and they went with it.”1

Mickey White and Rex Bell had been playing gigs as the Hemmer Ridge Mountain Boys, and when Townes came to Texas they again accompanied him. The Hemmer Ridge Mountain Boys had increasingly become a novelty band, featuring comedy bits in their act and actually recording a single version of

173

174

A Deeper Blue: The Life and Music of Townes Van Zandt

“Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother” sung in pig latin. In late 1979 and early 1980, White and Bell were glad to have Townes back and to have the chance to develop a more serious outlet for their music. “I was making a living playing with the Hemmer Ridge Mountain Boys,” White recalls, “but I really felt that we’d shot our wad as far as having an opportunity to move up.”

In what turned out to be the group’s final project—and their most lasting—in early 1980, they worked with Louisiana singer Lucinda Williams on her second album. “She approached me and Rex and Mike, our drummer, about being her backup band,”

White says. “She had this whole slew of new songs, which became

Happy Woman Blues

.” Mickey and Rex—and Townes—

knew Lucinda from their days in Nashville, “from the big house with Rex and Rodney Crowell and Skinny Dennis and everybody,” White says. “She had recorded an album for Folkways, doing all those traditional blues songs, then she moved into the songwriting thing, which I think she always wanted to do.”

That spring, with uncertainty about Townes’ future with his touring band, Danny Rowland had backed away from playing to return to school, so Townes asked Mickey White to accompany him and Jimmie Gray on a brief Texas tour. “Lo and behold,”

White says, “the old double guitars were clicking pretty good.”2

In the early summer of 1980, John Cheatham offered White a long-term job with Townes on a “major tour” of New England and the Northeast, including New York City. In the past year, Townes had played some dates in Vermont booked by semi-professional promoter Ron McCloud, who had now called Cheatham about a four- to six-week tour package he was assembling for Townes. According to White, “Townes came down in the Colonel, his truck, which he and Ruester and Jimmie had traveled around in—the gray Chevy six-cylinder pickup with a camper on it. We played a couple more dates down in Texas, and then, me and Jimmie Gray drove the pickup up to Vermont.3 Townes had some other kind of obligation, so he was going to fly up there and meet us.” They met Townes at McCloud’s house, along with Billy Joe Shaver, who was headlining the tour Still Lookin’ For You

175

with Townes. “Townes was real enthusiastic about the whole thing,” White says. “Cheatham was there, so we had some management, and we go up to Vermont and we end up at this beautiful 130-year-old farmhouse out there in the hills, kind of right in the center of Vermont. We were there two or three days in advance of the first gig, just ready to go.”

The first gig of the tour was at a bar in an old house that had been converted to a bed-and-breakfast on the town square in the village of Royalton, Vermont. “There were maybe about a hundred and fifty people, about half full,” White says. “It was certainly not a bust. Eddy Shaver was playing with Billy Joe … and it was really cool to see this kid that had become really good very fast.” Shaver had known Townes and Mickey for some years, “so it was a great reunion,” White recalls. The next stop was to be “the big gig” of the tour, the one “that was supposed to pay for this whole thing,” according to White. McCloud had rented a small concert hall just over the border in New Hampshire with the intention of showcasing Townes and Shaver along with several local acts. “But there was no promotion, no nothing,” White says. “We had this big hall, and Ron McCloud had put every penny he had into this gig, and nobody showed. I mean, maybe twenty people showed up. It was just a total, total bust.”

October began to unfold in the New England hills, and the road-weary Texans took note of the changing leaves and of a disturbing trend. “We became more and more concerned about what was going on with this little tour, and we became more and more aware that we needed to play the next gig just to get the money to get out of there,” White recalls. In the meantime, McCloud tried to sustain the group “by cashing hot checks all over the area to keep us in whiskey and food … very little food, lots of whiskey. It was starting to get like ten days between dates, and we were getting really, really drunk.”

White co-wrote a song with Townes during this time called

“Gone, Gone Blues.” According to White, “We got into listening to Muddy Waters’

Hard Again

album, and I came up with

176

A Deeper Blue: The Life and Music of Townes Van Zandt

this riff, which is basically the old blues riff, kind of based on

‘Mannish Boy.’ I wrote a couple of verses, then I went to Townes and I said, ‘Hey Townes, let me show you this. Remember those verses you used to make up for “Come On in My Kitchen”?’ We could never understand the words, and Townes had just made stuff up. I said, ‘Do you mind if I use that, and we’ll kind of co-write this song?’ … And, on the spot, he just wrote the rest of the verses of the song. So we were doing some things. We were picking and trying to keep the best foot forward, but it deteriorated pretty fast.”

Besides the gaps between jobs, the lack of income, and the bad checks, the group were becoming aware of a disturbing pattern, in which McCloud would announce just before a scheduled engagement that the gig had suddenly been canceled. “We became suspicious that these gigs weren’t there in the first place,” White says. “But then, lo and behold, the minute we got kind of antsy, one of them would come through.” By far the most notable gig that came through during this stretch was an engagement at Gerde’s Folk City in Greenwich Village, New York City.

“We all climbed into the Colonel and drove down to New York City,” White remembers. “For me, man, this was it. Gerde’s is where Bob Dylan played, Simon & Garfunkel, John Hammond, Phil Ochs, the whole crew. The joint was absolutely jammed.”

Rex Bell and his new wife showed up at the gig, as did friends from all over the country. Townes rose to the occasion. “Townes, man, he was just on fire,” says White. “It was one of the best gigs I ever saw the guy play … really striking that perfect balance of having just enough whiskey to get loose and be very witty and spontaneous and not too drunk.” In addition, it seemed to the musicians that they were playing to a deeply appreciative audience. White believes that Townes was feeding off of the energy of the crowd in a way he had only rarely seen. “As many times as I’d played with Townes, I’d never really been in awe of what he was doing while I was up there on stage with him, because I was usually so involved, making sure I was in tune and knowing what song we were playing next, kind of watching the crowd, Still Lookin’ For You

177

feeling the pace. This time, I was just standing up there blown away by this guy.”

Encouraged by the success of the Gerde’s gigs, the musicians headed back to Vermont ready for a final round of New England shows. A late cancellation meant that there would be a week until the next gig, and, with Townes leading the parade, they all began drinking more heavily to fill the interim. Jimmie Gray became concerned that things would get out of hand, and he moved into another house nearby with some people he had met in town. Mickey White, who was still suffering through a recent breakup, started “stepping up” his drinking to an alarming degree. “Man, that’s all we had to do,” he says, “waiting for another gig to come along.” As White recalls, “The leaves started going from all these brilliant colors to just falling off one by one…. Then, all of a sudden the cops are at the door looking for Ron McCloud for the hot checks that he’d been writing.”