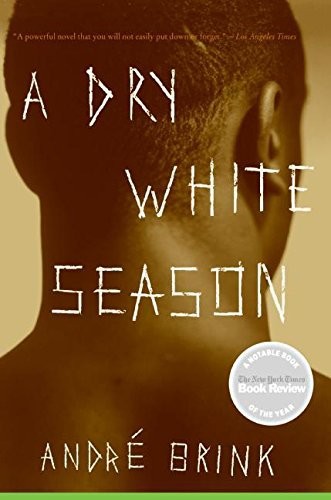

A Dry White Season

Read A Dry White Season Online

Authors: Andre Brink

A DRY WHITE

DRY WHITE

SEASON

ANDRÉ BRINK

For

ALTA

who sustained me in the dry season

Contents

Dedication

FOREWORD

ONE

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

TWO

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

THREE

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

FOUR

1

2

3

4

5

EPILOGUE

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Copyright

About the Publisher

I used to think of him as an ordinary, good-natured, harmless, unremarkable man. The sort of person university friends, bumping into each other after many years, might try to recall, saying: “Ben Du Toit?” Followed by a quizzical pause and a half-hearted: “Oh, of course. Nice chap. What happened to him?” Never dreaming that

this

could happen to him.

Perhaps that is why I have to write about him after all. I used to be confident enough that, years ago at least, I’d known him reasonably well. So it was unsettling suddenly to discover he was a total stranger. Or does that sound melodramatic? It isn’t easy to rid oneself of the habits of half a lifetime devoted to writing romantic fiction. “Tender loving tales of rape and murder.” But I’m serious. His death challenged everything I’d always thought or felt about him.

It was reported in a humdrum enough fashion – page four, third column of the evening paper. Johannesburg teacher killed in accident, knocked down by hit-and-run driver. Mr Ben Du Toit (53), at about 11 o’clock last night, on his way to post a letter, etc. Survived by his wife Susan, two daughters and a young son.

Barely enough for a shrug or a shake of the head. But by that time his papers had already been dumped on me. Followed by this morning’s letter, a week after the funeral. And here I’m stuck with the litter of another man’s life spread over my desk. The diaries, the notes, the disconnected scribblings, the old accounts paid and unpaid, the photographs, everything indiscriminately lumped together and posted to me. In our student days he constantly provided me with material for my magazine stories in much the same way, picking up ten

per cent commission on every one I got published. He always had a nose for such things, even though he himself never bothered to try his hand at writing. Lack of interest? Or, as Susan suggested that evening, lack of ambition? Or had we all missed the point?

Looking at it from his position I find it even more inexplicable. Why should he have picked on me to write his story? Unless it really is an indication of the extent of his despair. Surely it is not enough to say that we’d been room-mates at university: I had other friends much closer to me than he had ever been; and as for him, one often got the impression that he never felt any real need for intimate relationships. Very much his own man. Once we’d graduated it was several years before we met again. He took up teaching; I went into broadcasting before joining the magazine in Cape Town. From time to time we exchanged letters, but rarely. Once I spent a fortnight with him and Susan in Johannesburg. But after I’d moved up here myself to become fiction editor of the woman’s journal, we began to see less and less of one another. There was no conscious estrangement: we simply didn’t have anything to share or to discuss any longer. Until that day, that is, barely two weeks before his death, when he telephoned me at my office, quite out of the blue, and announced that he had to “talk” to me.

Now although I’ve come to accept this as an occupational hazard I still find it difficult to contain my resentment at being singled out by people who want to pour out their life stories on me simply because I happen to be a writer of popular novels. Young rugger buggers suddenly becoming tearful after a couple of beers and hugging you confidentially: “Jesus, man, it’s time you wrote something about a bloke like me.” Middle-aged matrons smudging you with their pale pink passions or sorrows, convinced that you will understand whatever their husbands don’t. Girls cornering you at parties, disarming you with their peculiar mixture of shamelessness and vulnerability; followed, much later, as panties are hitched up or a zip drawn shut, by the casual inevitable question: “I suppose you’re going to put me in a book now?” Am I using them – or are they using me? It isn’t me they’re interested in, only my “name", at which they clutch in the hope of a small claim on eternity. But one

grows weary of it; in the end you can hardly face it any more. And that is what defines the bleakness of my middle-aged writing career. It is part of a vast apathy which has been paralysing me for months. I’ve known dry patches in the past, and I have always been able to write myself out of them again. But nothing comparable to this arid present landscape. There are more than enough stories at hand I could write; it is not from a lack of ideas that I had to disappoint the Ladies’ Club of the Month. But after twenty novels in this vein something inside me has given up. I’m past fifty. I am no longer immortal. I have no wish to be mourned by a few thousand housewives and typists, rest my chauvinist soul. But what else? You cannot teach an old hack new tricks.

Was this one of the reasons why I succumbed to Ben and the disorderly documentation of his life? Because he caught me in a vulnerable moment?

The moment he telephoned I knew something was wrong. For it was a Friday morning and he was supposed to be at school.

“Can you meet me in town?” he asked impatiently, before I could recover from the surprise of his call. “It’s rather urgent. I’m phoning from the station.”

“You on your way somewhere?”

“No, not at all.” As irritably as before. “Can you spare me the time?”

“Of course. But why don’t you come to my office?”

“It’s difficult. I can’t explain right now. Will you meet me at Bakker’s bookshop in an hour?”

“If you insist. But—”

“See you then.”

“Good-bye, Ben.” But he’d already put down the receiver.

For a while I remained confused. Annoyed, too, at the prospect of driving in to the city centre from the journal’s premises in Auckland Park. Parking on Fridays. Still, I felt intrigued, after the long time we hadn’t seen each other; and since the journal had gone to press two days before there wasn’t all that much to do in the office.

He was waiting in front of the bookshop when I arrived. At first I hardly recognised him, he’d grown so old and thin. Not

that he’d ever been anything but lean, but on that morning he looked like a proper scarecrow, especially in that flapping grey overcoat which appeared several sizes too big.

“Ben! My goodness—!”

“I’m glad you could come.”

“Aren’t you working today?”

“No.”

“But the school vac is over, isn’t it?”

“Yes. What does it matter? Let’s go, shall we?”

“Where?”

“Anywhere.” He glanced round. His face was pale and narrow. Leaning forward against the dry cold breeze he took my arm and started walking.

“You running away from the police?” I asked lightly.

His reaction amazed me: “For God’s sake, man, this is no time for joking!” Adding, testily, “If you’d rather not talk to me, why don’t you say so?”

I stopped. “What’s come over you, Ben?”

“Don’t stand there.” Without waiting for me he strode on and only when he was stopped by the traffic lights on the corner I did catch up with him again.

“Why don’t we go to a café for a cup of coffee?” I suggested.

“No. No, I’d rather not.” Once again he glanced over his shoulder – impatient? scared? – and started crossing the street before the lights had returned to green.

“Where are we going?” I asked.

“Nowhere. Just round the block. I want you to listen. You’ve got to help me.”

“But what’s the matter, Ben?”

“No use burdening you with it. All I want to know is whether I may send you some stuff” to keep for me.”

“Stolen goods?” I said playfully.

“Don’t be ridiculous! There’s nothing illegal about it, you needn’t be scared. It’s just that I – “ He hurried on in silence for a short distance, then glanced round again. “I don’t want them to find the stuff on me.”

“Who are ‘they'?”

He stopped, as agitated as before. “Look, I’d like to tell you everything that’s happened these last months. But I really have

no time. Will you help me?”

“What is it you want me to store for you?”

“Papers and stuff. I’ve written it all down. Some bits rather hurriedly and I suppose confused. But it’s all there. You may read it, of course. If you promise you’ll keep it to yourself.”

“But—”

“Come on.” With another anxious glance over his shoulder he set off again. “I’ve got to be sure that someone will look after it. That someone knows about it. It’s possible nothing will happen. Then I’ll come round one day to collect it again. But if something does happen to me – “ He jerked his shoulders as if to prevent his coat from slipping off. “I leave it to your discretion.” For the first time he laughed, if one could call that harsh brief sound a laugh. “Remember, when we were at varsity, I always brought you plots for your stories. And you always spoke about the great novel you were going to write one day, right? Now I want to dump all my stuff on you. You may even turn it into a bloody novel if you choose. As long as it doesn’t end here. You understand?”

Other books

THAT MAN 5 (The Wedding Story-Part 2) by Nelle L'Amour

Girl Undercover 12: Showdown by Julia Derek

Hell on Heels by Victoria Vane

A Feral Darkness by Doranna Durgin

Cougar Needs [Cougarlicious 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) by Cooper McKenzie

Gene Mapper by Fujii, Taiyo

Blue Willow by Deborah Smith

Zika by Donald G. McNeil

Blood Song by Anthony Ryan

Righteous Lies (Book 1: Dancing Moon Ranch Series) by Watters, Patricia