A Grue Of Ice

Authors: Geoffrey Jenkins

1.

The Albatross' Foot

"

Drake Passage!"

I shook my head. Sailhardy was wrong. The thin, sharp

stiletto of wind did not even ruffle the surface of the sea, it was slight. It was there, though. Sailhardy unlashed the mainsail's crude fastening. His hands were as rough as the knotted wood of the whaleboat's ribs. The boom carrying the sail slatted untidily. Way dropped off the deep, thirty-foot craft. She

settled into her own reflection, yellow to yellow, blue to blue white to white. The islanders' garish sense of paint did nothing to conceal the sweet lines of the boat.

" South Shetlands," I countered.

Sailhardy didn't seem to hear me. He crooked

a

knee into the starboard forward rowlock. His action was unstudied,

but there was a pointer's tenseness in it. I found another lead sinker for my special net among the long oars on the gratings. I knotted it lazily to a hundred-fathom line coiled on the bottomboards. Sailhardy's taut caution seemed out of place. I suppose fishermen are fishermen the world over, and my enjoyment in sending down my special nylon net to the depths of the ocean here on the fringes of the Southern Ice Continent for tiny plankton sea-creatures was as keen as it would have been in casting a fly six thousand miles away in Scotland. Sailhardy's lean shoulders shrugged under the faded red-orange windbreaker. His was the inborn alertness which made

a

man survive the sea-enemy, in these Antarctic waters more pitiless than anywhere else in the world. I was fishing, and it lulled me out of feeling that I was a man with a mission, let alone a scientist of the Royal Society of London.

" No, Bruce . . ." he began.

I grinned at him as I dropped the heavy lead sinker over the side. The use of my Christian name still came a little hard off his tongue. After all, a lower-deck man does not call his captain by his Christian name. Not in the Royal Navy anyway. For two long, bitter years Sailhardy had been my leading torpedoman aboard H.M.S.

Scott

during the war. My job, as commander of His Majesty's South Shetlands Naval

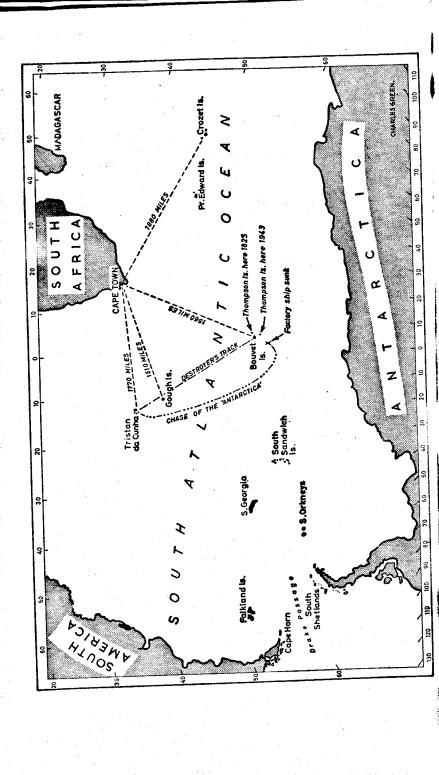

Force, based on Deception Island, five hundred miles south of the southernmost tip of South America, had been to guard the sea passage between the Pacific Ocean and the South

9

Atlantic—the Drake Passage. It was the favourite route for German-armed merchant raiders, U-boats and Japanese submarines. They chose it because its fog-bound waters, continually lashed by gales, made it impossible to find a ship, even if you were within five miles of it. I knew the Drake Passage —only too well. The name sang in my mind like a gale through the futtock shrouds of an old clipper. It was maybe fifteen years since I had last seen its wild waters from the bridge of my small destroyer, but its screaming hell-fiends of wind and ice still bit into my memory. Sailhardy's tenseness this quiet, sunny afternoon on the fringes of the wild ocean we had once guarded was a living memory, too, of the inborn sea-vigilance of a Tristan islander. Man against the sea. In these Southern

waters we both knew that the cards were stacked against the man.

I assumed my captain's voice. " Leading Torpedoman Sailhardy . . ."

I

couldn't help myself. I grinned at him again. His eyes were as far away as the horizon. " Relax," I said: " You look as if you were trying to see all the way to the South Pole."

"

I

wish

I could," he said. " Then I'd know what sort of

a

gale is due to hit us."

I gestured towards the quiet scene. The big island lay some miles astern of the boat, and two smaller ones were visible above the horizon ahead. They made a triangle with unequal sides roughly ten and twenty miles long. The big island was closest to us.

" Nothing is going to hit us," I said lazily. " Nothing at all." Sailhardy glanced back at the big island, his home, as if to take strength from its sombre cliffs.

" The watch never goes below on Tristan da Cunha," he said with a curious intonation. " That is why we islanders have survived. There's a great storm behind this little wind." I, too, turned and looked at the near-by island. A giant flock of Cape pigeons made a white socket of light against

its towering throne of darkness ; matching their whiteness, a crown of snow rimmed the island's 7,000-foot extinct volcano: Tristan da Cunha, the loneliest inhabited island in the world. It lies, with its two tiny neighbours whose summits I could just see ahead, midway between Africa and South America on a line between Cape Town and

Montevideo, and an almost equal distance of two thousand miles from the nearest tip of the Antarctic ice continent. Before and immediately after Napoleon's time Tristan da

10

Cunha was an important base for British and American sealing ships making for the hunting-grounds of the frozen South. Its first three permanent settlers, half a century before the Civil War, were, in fact, American sailors. During Napoleon's exile on St. Helena, 1,500 miles to the north-east, the British stationed a garrison on Tristan, and the remains of that garrison, plus the Americans, formed the stock from which the island's present inhabitants have sprung. For nearly a century and a half, the island remained cut off from the world, except for a rare visiting ship.

During the war I had brought to Tristan from Cape Town

a

force of Royal Navy and South African Air Force men to man a radio station. From Tristan I had taken my small task force under H.M.S.

Scott

two thousand miles to the south and had based in on Deception Island, a flooded volcanic crater on the edge of the ice continent. The two neighbours of Tristan I could see ahead now were Nightingale and Inaccessible Islands. In every direction beyond them, for thousands of square miles, lay completely empty sea.

The Cape pigeons, in splendid white resilience, made for the haven of Tristan da Cunha. Sailhardy unhooked the triangle of foresail forward of the mast, as if to emphasise the danger he feared.

I could not take his forebodings seriously. It was all too peaceful. I was to learn—soon—how much of my ice-lore I

had lost.

" I'm a scientist," I replied easily. " I've got a posh title to prove it—holder of the Royal Society's Travelling Studentship in Oceanography and Limnology. You do the sailing."

He caught my mood, and grinned back. " I remember I was nearly sick with fright when you took me aboard H.M.S.

Scott

from Tristan during the war. Naval captains were God to me."

" Who ever told you to address me

as

professor-captain that day?" I laughed.

" One of the midshipmen," he said. " He told me the captain had been a professor of science in peace-time before commanding the ship." He grinned at his own discomfiture. " So you had to be professor-captain."

" I wasn't a professor," I said. " Never have been. I'd merely made special studies in oceanography. I was too young anyway to be a professor."

" You were twenty-seven then," he said, " that makes you fortytwo now." 11

I remembered his hesitation a few minutes before about my Christian name. " I'll bet that the day you walked on to my bridge you never thought you would be calling me Bruce," I said.

" Bruce." He paused a moment, and then went on: " You would have remained Captain Wetherby to me all my life—

if it hadn't been for what you said that day you came back

to Tristan after the war. That's twelve years ago now. We

Tristan islanders live a hard life. We live off the sea, except for a couple of acres of potato patches and some apple trees, and maybe a hundred cattle and sheep. You had the world at your feet after the war. You'd had a brilliant war-time career, and a brilliant university career before that. I remember how you stepped off the freighter out in the roadstead. Mine was the first boat there. I didn't know you were coming. ' Captain Wetherby!' I said. I'll never forget your reply. ' No, Sailhardy. This is Bruce. Captain Wetherby went down with the raider. I've come back to the things I want—

Sailhardy, Tristan, the Southern Ocean.' "

I played it lightly. " You forget, I said I wanted your boat, too." I smiled.

He gave a low laugh. Tristan's long isolation from the world has left the islanders a curious heritage—even to-day, their speech is a strange mixture of English West Country speech shot through with the twang of long-dead New England whalermen, drawn out and enduring as the West Wind Drift.

" My boat," he said. " That is to ask everything from a Tristan islander. We are the poorest people in the world. A boat like this makes me one of the richest men on the island. A boat, you said: you would need a boat to try and find one of the greatest sea mysteries."

Sailhardy stowed the mainsail and his eye ran affectionately over the whaleboat, with its six long oars lashed to the bottom gratings. Just as the Viking long-boats gave Greenland the kayak, the New Bedford whalers left the secret of their fast, seaworthy chasers to Tristan. And the islanders, born and bred to the sea, added to that knowledge, until to-day the Tristan whaleboat is as indigenous to the lonely island as a Baldie to Leith or a Sixern to the Shetlands. There is almost no wood on Tristan, so the islanders make them of canvas. The wood for the ribs—

as precious and as scarce as fine gold—comes from the stunted, wind-lashed apple trees that cling for an existence 12

under walls alongside the stone houses, which are sunk half underground like Hebridean crofters' cottages to escape the gales. I noticed that the forward port-side strake of Sailhardy's boat was splintered ; it would remain so, just•

because there was no timber to spare for repairs. The boats are daubed—one can hardly call it painted—in bright, garish colours of yellow, blue and white. It is for a purely functional purpose, to waterproof the canvas, and they splash on whatever paint they can find, or beg from the occasional ship. The boats are the finest sea-going craft in the world. I would go anywhere with a crew of ten Tristan boatmen and a Tristan whaleboat. The boatmen have been apprenticed the

hard way by the great seas, and they have learned to bring

in the whaleboats to Tristan's rough shingle beaches and rockstrewn cliffs in a way which even

to

my sailor's eye

is

uncanny.

A hunk of kelp, as thick as a man's body, and perhaps twenty feet long, drifted past. We were about five miles from Tristan, which is ringed by a huge barrier of kelp. Inside that barrier the sea is tamed by the fronded fetters to a grey sullenness. Sea mystery! In that moment I wished that the drifting length of kelp was the pointer to the mystery I had come thousands of miles to try and find,