A Gull on the Roof (10 page)

Read A Gull on the Roof Online

Authors: Derek Tangye

It was not only for this reason that we decided to seek the advice of a second dowser. That evening we were in Jim Grenfell’s pub when someone said: ‘That fellow may be wrong . . . now the man you want is old John Henry. He’s never been wrong in his life and he’s nearly seventy . . . he’ll find you a spring if anyone can.’ I was still cautious and during the following few days I asked other people in the district. ‘Oh, yes,’ everyone said, ‘John Henry is the dowser you’re looking for.’ The Cornish, like the Irish, are adept at providing those remarks which, they sense, will bolster your personal hopes; and in this case no one wished to tell me that old John had given up regular professional dowsing and that, as he himself later put it: ‘I be afraid my sticks have lost their sap.’ It was so apparent I wanted our dowsing to be a success that to cast a doubt on my hopes would have been an offence.

The old man had kindly blue eyes wrinkling from his gnarled, weather-beaten face, a character who was so much the countryman that the mind, in his company, was blind to any conversation other than that which concerned the open air. I told him about the other dowser and pointed out the spot where the spring was supposed to be. ‘The trouble is,’ I said, ‘it’s so near the cottage that I don’t see how we could sink a well.’ The old man stared at the soil deep in thought, then pulled his forked hazel twig from his pocket, steadied himself as if he were trying to anchor his feet on the ground, and began to dowse. I looked at Jeannie and smiled. I felt I knew what was going to happen; and a moment later the old man swung round to me crossly. ‘Minerals,’ he snorted, ‘not water.’

For the next hour he wandered about while we followed as if we were in the wake of a sleepwalker. Sometimes he would stop and the stick would dip, but never, it seemed, in a way that satisfied him. ‘Look,’ I would cry out hopefully, ‘it’s dipping!’ But the old man only replied by smiling mysteriously. And then we went up to the crest of the hill above the cottage to a point a few yards from the wire netting of the chicken run. Once again he steadied himself, held out the stick horizontally, gripping it as if he were afraid it might catapult from him. It dipped . . . quickly, strongly, as if it were making a smart bow. The old man broke into smiles. ‘Here’s your spring!’ he cried out triumphantly, ‘come and feel for yourselves!’ I first held the twig by myself and nothing happened; but when he clasped my wrists a power went into that stick as if it were a flake of metal being sucked by a magnet. ‘Now there’s a strong spring,’ said John Henry, ‘and you won’t have to go more than fourteen or fifteen feet to find it. You can be sure of that.’

Fourteen or fifteen feet. It seemed simple. Jeannie gaily waved goodbye to the old man expecting the water to be gushing into a kitchen sink within a month.

Within a month – the chickens having been moved to a place of safety – there was a hole in the ground seventeen feet deep, eight feet square, and the bottom was as dry as soil in a drought. Its creators were two miners from the Geevor tin mines at St Just, Jack Tregear and Maurice Thomas, and they were as distressed as we were; while old John, hastily called in again by me when the fifteen-feet limit was reached, nervously scratched his head and said: ‘If you go another foot there’s sure to be water.’

It was all very well for him to lure us downwards, but for how long were we to pour money down a hole chasing a spring which might not be there? And yet we had gone so far that the tantalising prospect existed of a spout of water waiting to be released within a few inches of where we might stop. We were, of course, given plenty of advice. ‘Ah,’ said a neighbour, ‘you should have had Visicks the borehole drilling people. They reckon you have to bore one hundred feet to get a good supply. They charge thirty shillings a foot, but’ – looking lugubriously down our hole ‘ – they do get results.’

One hundred feet! And here we were at seventeen feet wondering whether to call a halt. The miners had hoped to complete the work within their fortnight’s holiday and at their charge of £2 a foot I had expected the well to cost £30. But from the beginning the plans went awry. Instead of being able to dig the first few feet with pick-axe and shovel, the miners came across solid rock within a foot of the surface. Dynamite had to be used and dynamite meant the laborious hammering of the hand-drills to make the holes in which to place the charges. Three or four times a day Jack and Maurice would shout ‘Fire!’ – and scamper a hundred yards to the shelter of a hedge while we ourselves waited anxiously in the cottage for the bangs. One, two, three, four, five, six . . . sometimes a charge would fail to explode and after waiting a few minutes the miners returned to the well to find out the reason; and there was one scaring occasion when Jack, at the bottom of the shaft, lit a fuse which began to burn too quickly. He started scrambling up the sides, pulling himself by the rope which Maurice held at the top. These events added to our distress. The well was a danger besides being a dry one.

I was now paying them by the hour instead of by the foot and the account had reached £50 without value for money except the sight of a splendid hole. It was a hole that taunted us. It laughed at us. It forced us to lean over the top peering down into its depths for hours every day. ‘Now let’s go and see how our hole’s getting on,’ Tommy Williams would say as often as he felt I would not mind him dropping the work he was doing. The miners had carved a rectangle and the point where John Henry’s stick had dipped was its centre; the sides were sheer, the slabs of granite cut as if by a knife. We would stare downwards and when our eyes had grown accustomed to the dark we would gaze at the veins which coursed between the dynamited rocks; the veins through which, if a spring was near, the water would flow.

The miners would make hopeful comments and Jack would shout up from the depths: ‘The rab here feels damp.’ By now the hole had become a talking point in the district and monotonously I would be asked, ‘Any luck yet?’ It became, too, the reason for a walk and in the evening or at the weekend neighbours and far neighbours would lope towards it and add their opinions as to its future. ‘Now I reckon you’ll have to go thirty feet before you strike water,’ said one. ‘My cousin Enoch found plenty at twenty,’ said another. ‘In Sancreed parish,’ said a third, ‘there are two wells within a mile of each other forty feet deep and never a drop of water from either.’ Tommy Williams would comment about these remarks with acid sharpness. ‘That fellow,’ said he about one who prophesied we were wasting our time, ‘is worried about his own water, he’s frightened we might drain his.’

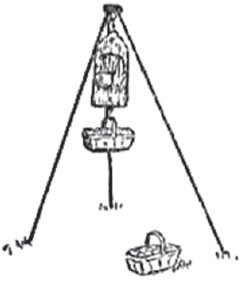

We were down twenty feet, then twenty-two, then twenty-five. By now, made frantic by the tortoise pace of the hand-drills, we had hired a compressor and the drills to drive into the rock. It speeded the blasting but there was still no sign of a thimbleful of water. Twenty-six feet. Our money was falling into that hole with the abandon of a backer doubling up on losing favourites; and sooner or later we would have to stop. But when? We now had planks across the top and a winch to pull up the debris after each blast; and back we brought old John Henry to stand on the planks so that we could see again the reaction of his hazel stick. Down it dipped, relentlessly, a powerful character staunch to its original opinion. ‘If you go another foot . . .’ said John.

It was that evening I met the manager of the Newlyn Quarry to whom I described the nightmare in which we were involved. He was a young, Rugby-three-quarter-type of man who considered my story as a challenge to himself and his organisation. ‘I have some compressor equipment and some new drills I want to try out,’ he said with a light in his eye, ‘we’ll bring them out next weekend and we’ll have a helluva bang.’ The following Saturday a caravan from Newlyn wormed its way through gates and across fields to within a few yards of the hole. A shiny new compressor with a tractor to power it, the manager and his foreman, two quarry men in snow-white overalls and polished black helmets who moved speedily about arranging the equipment with the expectant air of conjurers before a children’s party. By Monday, I said to myself, we will have water. By Monday the hole was thirty feet deep and my friend had offered to return the following weekend.

Down the hole the next Saturday went a quarry man, the compressor started up its whining roar, the drill spat like a machine-gun, and the dust began to rise, blanketing the bottom. I hung around with the others bemusedly chatting, dazed like a boxer after a fight. ‘When I was a child,’ I was saying to the foreman, ‘I started to dig my way to Australia . . .’

Suddenly from the murk below us was a shout. ‘Water! I’ve struck water!’ We let out a cheer which may have been heard across Mount’s Bay and I ran around shaking everyone by the hand like a successful politician after an election. Water! It was as if I had won a football pool. I ran down to the cottage where Jeannie was patiently kneading dough on the kitchen table. ‘They’ve found it!’ I cried. ‘Water! . . . old John Henry was right!’

But Jeannie was going to wait a year for her bath and her indoor wash-basin. For one thing our money had gone down the hole. For another, the water turned out to be a ‘weeper’ which seeped into the well at a gallon or two an hour. And the third reason was that the rains had come. The water butt was full.

Monty hated the proceedings of the well, and the bangs frightened him into remembering the bombs, flying bombs and rockets which were the companions of his youth; and into remembering the night when, the dust of the ceiling in his fur, he hid terrified in the airing cupboard at Mortlake while Jeannie and I frantically searched the neighbourhood believing he had bolted after a bomb had blown the roof off the house. Thus Jeannie, as soon as the miners shouted ‘Fire!’ always sat beside him, stroking him, until the bangs were over.

But his contentment, these events apart, was a delight to watch and as the months went by he quietly eased himself into the comfortable ways of a country gentleman. He hunted, slept, ate; then hunted, slept, ate. He never roamed any distance from the cottage, but sometimes he would disappear for hours at a time and we would walk around calling for him in vain. He was, of course, curled up in some grassy haunt of his own and he would reappear wondering what all the fuss was about; and although the reason for our searches was mainly due to the simple curiosity of wanting to discover the whereabouts of his hiding places, we also possessed secret fears for his safety. He was, after all, a London cat and therefore could not be expected to have the intuition of a countryman; and we were prepared to appear thoroughly foolish in any efforts we made to protect him. Our concern was due to three reasons – the fact that the colour of his fur made him look, from a distance, like a fox; rabbit traps; and because we knew that sometimes foxes kill cats. And if, by our behaviour, it looked as if we possessed neurotic imaginations, the future proved our fears were justified.

There was, for instance, the young man with an airgun whom I saw emerge from our wood and begin to stalk, the airgun at the ready, up the field at the top of which Monty was poised beside a hole in the hedge. ‘What are you doing?’ I yelled, running towards him; and the young man who, in any case, had no right to be there, halted for a moment, looking in my direction and began to make grimaces as if he were trying to tell me to shut up. Then crouching, he began to move forward again. ‘Stop!’ I shouted again, ‘what the hell are you up to?’

I reached him panting, and he stared oafishly at me. ‘Have you any chickens?’ he said bellicosely.

‘I have . . . but what’s that got to do with it? You’ve no right to be here.’ He looked at me with disdain. ‘I was doing you a favour. I saw a cub at the top of this field and if it hadn’t been for you I could have shot it.’ At that moment Monty sauntered down the field towards me. ‘A cub?’ I said.

The young man went red in the face. ‘It looked like a cub!’

Monty was given the freedom of the window at night and paradoxically, though our fears for him were bright during the day, they were dulled at night. We were deluded, I suppose, by the convention that cats go out in the dark and that a kind of St Christopher guards them from danger. Then one day a neighbour told us he had found the skeletons of three cats outside a fox’s earth not half a mile from the cottage. ‘There’s a rogue fox about,’ he said, ‘so you’d better look out for your Monty.’ A rogue, by its definition being something which does not pursue normal habits, earns odium for its whole species. Badgers, for instance, are generally supposed to be chicken killers but there is unchallengeable evidence that they are not; it is the rogue badger who has brought them their bad name. So it is with foxes – only the rogues kill cats; but once a rogue gets a taste for cats a district will not be safe until the fox is killed. But even after this warning we did not interfere with Monty’s nocturnal wanderings. We were aware of the rebellion we would have to face if we tried to stop him, and so we preferred to take the easy way out and do nothing at all. He was agile, he could climb a tree if attacked and, as he never went far, he could always make a dash for the window.

Then one night Jeannie was woken by a fox barking seemingly just a few yards from the cottage, and this was followed by a figure flying through the window and on to the bed. The following night we were determined he should stay indoors, and we gave him a cinder box and shut the bedroom door; and a battle of character began. He clawed, battered and cried at the door while Jeannie and I, trying to sleep, grimly held to our decision that he should

not

go out. At dawn we surrendered. ‘After all,’ argued Jeannie, as if cats cannot see in the dark, ‘it is light enough for him to see a fox if one is about.’ Our bed lay against the wall which contained the window, and the window was so placed that with my head on the pillow I could watch the lamps of the pilchard fleet as it operated in Mount’s Bay; while beyond, every few seconds, there was the wink of the Lizard light. Three feet below the window was the rockery garden and the patch of trodden earth on which Monty jumped when he went out on his adventures – one moment he could be on our bed, the next outside.