A Higher Call: An Incredible True Story of Combat and Chivalry in the War-Torn Skies of World War II (15 page)

Authors: Adam Makos

A WEEK LATER, EARLY SEPTEMBER 1942, NEAR AMBERG

F

RANZ APPROACHED THE

door to the pub. He smoothed his grayish-blue blazer and pulled its yellow collar tabs. His crush cap sat straight on his head, so he cocked it at a jaunty angle like the other veterans did. A tan cloth band encircled the left cuff of his blazer and read

AFRIKA

, a badge that only men who had fought there could wear. He cinched his black tie. The tie was not just for special occasions. The Air Force fashioned itself as Germany’s most gentlemanly military branch. Everywhere but in the desert, German pilots wore ties, even when flying.

Inside the pub, Franz strolled up to the brewmaster’s daughter, the girl of his teenage dreams, whose blond hair and busty influence had helped steer him away from the priesthood. Franz beamed a wide smile and removed his hat, revealing his hair neatly slicked back, with the sides and back cropped short. The girl emerged from behind the bar, looked him over, and stopped an awkward foot away from him. Franz

gazed at her. She slapped him hard on the cheek. Smarting, Franz looked at her wide-eyed.

“Aren’t you ashamed to be here?” the girl snapped.

“What’s wrong?” Franz asked, his eyes wide with surprise.

“Get out! Get out! Get out!” she screamed.

Franz hesitated and asked again what he had done wrong. The girl threatened to call her father. Franz ran for the door.

That night, Franz sat with his mother as she sipped a beer. Every night, without fail, she always drank a beer. Franz confessed his woes with the brewmaster’s daughter. His mother shrugged with a guilty grin. Franz realized she was somehow behind the slap he had received. He asked his mother what she had done. His mother admitted that when Franz had departed for Africa, he had left so many girlfriends behind that each wrote to her, seeking for news of him. She did not reply. So the girls wrote again and again. Then they started coming to her door to ask about Franz. Annoyed, Franz’s mother wrote a letter to each girl that said: “Franz is married! Leave him alone!” Franz broke out laughing at his stern old mother. He knew she probably still prayed he would come to his senses and become a priest.

Franz’s holiday was supposed to last eight weeks, but he found himself wanting to return to the desert sooner. When he biked around Amberg, his friends’ parents told him where their boys had been deployed. Every morning when he rustled open his newspaper, the headlines revealed bad news from the African front. JG-27 lost forty-victory ace Sergeant Gunther Steinhausen, and a day later, fifty-nine-victory ace Stahlschmitt, both killed.

Three weeks later, the headlines screamed in big black letters that Squadron 3’s hero of the desert, Marseille, was dead. Franz read the story in shock. It said that Marseille had died bailing out of his fighter after a combat mission. But Franz knew there had to be more to the story that no one was saying. The Desert Air Force could never kill Marseille.

As his leave wound down in October, Franz’s orders changed; he was told not to return to his unit because JG-27 was withdrawing from the desert. Africa had become a lost cause for the Germans. The British had launched an attack from El Alamein, a push that Rommel was unable to stop. In early November, as the Germans retreated, a new foe landed behind them in Casablanca: the Americans. When the first American flyer was captured, Neumann invited the pilot to join him for breakfast. Neumann was amazed that the American, a major, wore only a one-piece, olive-green flight suit. Neumann looked upon the enemy flyer with great worry as the American happily ate his breakfast. He knew that behind that one man stood the might of the American industrial empire. Neumann lost his appetite.

Around the table with his father and Father Josef, Franz came to the same conclusion—and worse. They agreed that the war had already been decided, ever since June 1941, when Hitler attacked the Soviet Union and opened a two-front war. Hitler had told his people that Stalin was about to attack them, but the truth did not matter. The older men had already lost a war in 1918 and knew how a nation’s doom played out. They knew at that moment, in November 1942, that Germany was going to lose the Second World War.

“What do I do now?” Franz asked his elders.

“You’re a German fighter pilot,” Franz’s father said. “That’s all there is to it.”

Father Josef nodded, having been a fighter pilot himself. Although he never spoke of his war stories, he told Franz something he would never forget.

“Don’t worry,” he said. “We fight our best when we’re losing.”

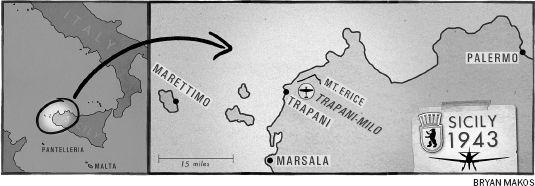

SIX MONTHS LATER, APRIL 13, 1943, NORTHWEST SICILY

H

IDDEN IN THE

shade of an olive tree, the white nose cone of the gray Bf-109 began to spin, its black blades catching the midday sunlight that snuck through the branches. The engine whined, coughed, and belched white smoke before settling into a powerful rhythm. Franz sat in the cockpit, a pipe clenched in his teeth. He wore just his tent cap, no flight helmet, no ear protection, and worked the throttle of the new 109.

Mechanics in oil-stained T-shirts and baggy khakis watched from the side of the spinning prop. Sicily was as hot as the desert, but unlike Africa, Sicily had trees, flowers, and streams around which high scrub bushes grew. At Trapani Airfield, the Squadron 6 mechanics preferred to work in the shade at the south corner of the base, far from the “big target” hangars on the north end. The lead mechanic leaned into the cockpit and studied the gauges.

“She’s still running hot,” Franz insisted to the mechanic who leaned in to hear Franz’s words.

Yellow 2

was a new Gustav, or G-4, model, fresh from the factory. With its new camouflage scheme, the

fighter looked like a sleek gray shark as it vibrated in the olive grove. The plane’s flanks and wings were gray, its belly was white, and along the fighter’s spine ran a wavy swath of molted black. A yellow

2

stood starkly from its camouflage.

Franz shut down the plane and hopped out. The mechanic insisted that Franz must be imagining problems. Franz reminded the mechanic that a G model had killed Marseille.

Franz had learned the story of Marseille’s death when he reunited with the unit. When JG-27 had been issued the new G models, Marseille had refused to fly his and had barred his pilots from doing so because the plane’s new, more powerful Daimler-Benz engine was prone to failure. After General Albert Kesselring heard that Marseille was casting doubt on the G, he ordered Marseille to fly the new plane anyway.

That’s how Marseille died. He had been flying home from a mission when a gear in his G model’s engine shattered and broke the oil line. Smoke billowed into his cockpit, blinding and disorienting him. Marseille failed to notice that his plane had slipped into a dive. When he jumped, instead of falling beneath the plane, the airflow sucked his body into the plane’s rudder. The same rudder that had borne his 158 victory marks had smashed Marseille’s chest, rendering him unconscious and unable to deploy his chute. Marseille’s friends had watched helplessly as he fell to earth. His comrades later returned to the airfield in a

kubelwagen

with Marseille’s body resting across their laps. In a palm grove, they displayed his casket in the bed of a truck. After burying Marseille, they gathered in a tent and listened to his favorite song, “Rumba Azul,” on his gramophone. A month later, they had to be removed from combat due to shattered morale.

The mechanic promised Franz he would take a look. His men reached for their tools, propped up the engine cowlings with rods, and began ratcheting off the engine cover.

Franz departed, darting across the runway with his life preserver in one hand and his flight helmet in the other. Small, silver flare cartridges lined the tops of his boots like bullets. The flares were a necessity now that he regularly flew over water.

Across the runway to the north lay the small village of Milo, with its flat, white roofs. Beyond it stood the massive dusty-looking Mount Erice, which looked like it belonged in the American badlands. Roedel kept his headquarters there, in a cave just below the summit. Atop Erice, an ancient, abandoned Norman castle clung to the mountain’s eastern lip. Called “Venus Castle,” the towers and walls had been built over an ancient temple to the Roman Goddess, Venus. Franz often envisioned ghostly knights staring down on the airfield from the ramparts. A month earlier, the group had deployed to Trapani Airfield from Germany. Roedel had promoted Franz to staff sergeant and placed him in Squadron 6 under Rudi Sinner, thinking the humble pilot a better influence than Voegl, whom Roedel had dispatched to lead a detachment in Africa.

Franz ambled along the flight line where the new 109s of Squadron 6 sat in gray brick blast pens held together by white mortar. Squadron 6 was nicknamed “the Bears,” because they had made the Berlin Bear their mascot and painted it on their patches. Franz saw his comrades lounging in the grottos behind their planes. The pilots sprawled in white lawn chairs and sipped herbal tea and iced limoncello. Franz felt the cool breeze of the ocean and thought how Sicily seemed a far better place than Africa.

Franz stopped in his tracks. The wind carried a rumble that Franz had come to dread in the days before. It was the deep hum of a swarm of metal wasps high above.

Thump! Thump! Thump!

Three bursts of anti-aircraft fire exploded on the edge of the airfield, the signal for “Air Raid!”

Pilots ran from the grottos for their 109s. Franz sprinted toward his plane. His heavy, fur-lined flying boots pounded the dry earth, and Franz wished he wore slim cavalry boots like the pilots had in the Battle of Britain days.

The droning grew louder. Franz glanced up between strides and saw twenty or thirty little white crosses at fifteen thousand feet on the southern horizon, flying toward him. His fears were confirmed—they were the Four Motors—the planes the Americans called the “B-17 Flying Fortress.”

Still running, Franz neared the mechanics’ grotto. He saw the lead mechanic emerge, waving his arms. “She’s not ready!” the mechanic shouted. Franz cursed his new 109. Wheeling, Franz decided that if his own plane was down, then he could borrow someone else’s. At the first blast pen, he found a 109 fueled and ready, its cockpit open. A crewman waited with the starter handle, ready to crank the plane to life, while another waited on the wing root to help a pilot strap in. Franz grabbed the handhold behind the cockpit to haul himself up, but another hand pulled him back down. A voice shouted at his back, “She’s mine, Franz!” Franz turned to see Lieutenant Willi Kientsch pull himself up and onto the wing. Willi looked more like a pale Italian teenager than a fighter pilot. His black eyebrows drooped like arches over his lazy eyes. Short, slight, and scrappy, Willi was just twenty-two years old but already had seventeen victories, the same as Franz. Franz cursed and ran to find another plane. Although Franz and Willi were tied for victories, they were not rivals. Willi was Franz’s best friend in the squadron, and Franz knew he had the right to claim his plane. At the next 109, Franz got as far as the wingtip when another pilot

shouted, “Don’t even think about it!” as he tossed his helmet up to the crewman and climbed aboard.