A Higher Call: An Incredible True Story of Combat and Chivalry in the War-Torn Skies of World War II (26 page)

Authors: Adam Makos

A

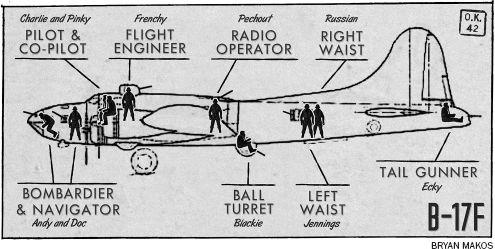

FTER VISITING THE

equipment shack, Charlie and his crew gathered outside the briefing hall, each man fully dressed in his leather gear. The sky was still deep with night, so the men stood beneath a streetlight to make their final preparations. The gunners wore their leather flight helmets, having forgotten that they were still an hour from takeoff. On the sidewalk beside them sat their parachutes and their yellow life preservers. In a nearby parking lot, a dozen deuce-and-a-half GI trucks idled, each waiting for crews to climb aboard for a ride to the planes.

Charlie chuckled at the thought:

“The Quiet Ones” have never been this quiet.

Each of the wiry boys looked a hundred pounds heavier in his heavy leather pants and jackets. The officers’ chestnut-brown jackets were crisp and looked thin next to the gunners’ thick jackets with puffy fleece collars. Charlie had heard that Blackie had wanted to paint his jacket before the mission.

“What will you put on it?” one of the gunners had asked him. “We don’t even have a regular plane.”

“The Quiet Ones,” Blackie had said. The gunners had burst out in laughter. Only Ecky, the short, sad-faced tail gunner shared Blackie’s sentiment. When he showed up to fly that morning, Ecky was the only one among “The Quiet Ones” with his jacket painted. In lieu of a plane’s name, someone had painted “Eckey” for him, in tall, white, scrolly letters, across his jacket’s shoulders.

Pinky handed out escape kits to the crew. Each kit contained a small waterproof bag with a map of Europe, a button-sized compass, and French money. Frenchy’s face lit up at the sight of French currency and the idea that if they were shot down on the way to Germany, the Army wanted him to aim for France to seek out the French Resistance. Pinky handed each of the guys a Mars candy bar. Ecky said that if anyone did not want his bar, he would like it. The men, except for Pinky, piled Ecky’s arms with candy. None of them had the stomach for

sweets. Pinky frowned; he could have eaten it all. Charlie had slipped his chocolate bar into his front pocket but pulled it out and tossed it to Ecky.

As a crew, they waddled to the trucks, each man carrying his cumbersome gear. Charlie saw his flight leader, Walt, waiting to board. Walt invited Charlie to hitch a ride with his crew. Walt’s crewmen boarded first then helped pull each man of Charlie’s crew up and over the lift gate.

In the dim gloom of 6:45

A.M.

, the truck drove the crews past B-17s that sat atop concrete parking clusters, each shaped like a three-leaf clover. One plane sat on each leaf. Frost covered the bombers’ noses. Large green tents lay outside each clover. Dark smoke piped from the tents and light glowed from within. Inside, mechanics lingered over coal stoves to keep warm. The mechanics had been on the job, working to get more than twenty planes ready by daylight. Now their work was almost through.

The truck stopped, and both Charlie’s and Walt’s crews hopped to the frozen earth. Looking past the cold, dead wheat fields, Charlie could have sworn the ocean lay just over the next hill. All of England felt like the coast to him, the way the clouds billowed up from the horizon. Often he swore he could smell the ocean, even though Kimbolton lay nearly one hundred miles inland. Charlie turned his attention to his “lady,” the B-17 with tall red Gothic letters with white outlines that announced her name:

YE OLDE PUB

. Charlie affectionately nicknamed her

The Pub

. She sat quietly next to Walt’s plane, which lacked nose art.

“Sorry about giving you Purple Heart Corner,” Walt told Charlie. “But don’t worry. Just stick close to your wingman.” Charlie promised he would. He and Walt shook hands, and Charlie went to say “Good luck,” but Walt cut him off mid-sentence. “We never say that,” he said. Charlie apologized. “Go get ’em,” Charlie said awkwardly, searching for words. “That’s better,” Walt chuckled. “Never say ‘good-bye’—it’s bad luck.”

Charlie saw the light from his crew’s flashlights bobbing toward the bombers’ hatches then disappearing within. The men were heading inside the plane to stow their chutes, inspect their guns, and check their ammo.

The bomber’s crew chief, Master Sergeant “Shack” Ashcraft, approached Charlie. One of the 379th’s original crew chiefs, Shack was twice Charlie’s age and had a tough, lean face and a head that looked to be shaved beneath his olive-colored skull cap.

“How’s she doing, Chief?” Charlie asked.

“Good enough, sir,” Shack said. He warned Charlie that engine four was acting up when they started it. “She seems okay now, but I’d watch her,” he added.

Shack seemed a bit distant, and Charlie suspected why. Rumor had it that Shack had lost three planes so far—three crews. Shack said the bomber was new to the group, a transfer from another unit, and that he was just learning her quirks. His words struck Charlie like a waiver.

Charlie began his walk-around inspection of the $330,000 aircraft. He beamed his flashlight on her patches from past bullet holes and felt comfort in knowing she was a veteran who had been “there” before. “There” was five miles up, a place without oxygen and devoid of the earth’s warmth. There, her living crew would fly and fight in a netherworld of clouds and stranded ghosts.

Satisfied that

The Pub

was secure, Charlie placed his life preserver over his head and clipped it around his waist and under his leg. He approached the nose hatch and stopped. He knew that pilots were supposed to swing up and into the hatch, as he had seen veterans do. It took muscle and guts to enter the bomber from that direction. If a man lost his grip and fell, it would be a painful backward tumble, headfirst onto the tarmac. Entering the bomber that way was showy— “raunchy” as the veterans called it.

Toting his parachute, Charlie ducked under the nose and kept walking all the way to the rear door on the right side of the plane, just ahead of the tail. There, he entered the bomber, like a gunner would.

Inside the plane, Charlie shined his flashlight down the narrow corridor toward the tail guns. The light’s beam revealed Ecky crawling toward him. Ecky smiled like a raccoon caught in a spotlight.

“Guns and oxygen okay back there?” Charlie asked Ecky. Ecky nodded. When Ecky smiled, it seemed he needed to work hard to lift his hangdog cheeks.

Charlie walked past the waist windows where Russian and Jennings worked the bolts and checked the breeches of their machine guns. They leaned their guns skyward and stood aside like soldiers on review as Charlie slipped between them.

Charlie dodged the ball turret and its support pole that ran from floor to ceiling. He found its gunner, Blackie, checking the ammo in the radio room where the men always stored it during takeoff to keep weight over the wings. Blackie was writing his name in chalk on some of the boxes, marking them as his. He was known to have a heavy trigger. Once airborne, he and the other gunners would claim their ammo to lock and load. Blackie would lower himself into his ball turret, known as “the morgue,” and the radio man, Pechout, would seal him inside. Gunners feared assignment to the ball turret, although time would prove it was actually the safest gun position.

Charlie passed Pechout, who pursed his lips as he listened to a headphone. Pechout tuned the glowing radio dials and tapped the Morse code button as a test.

Moving forward to the bomb bay, Charlie eyed the twelve five-hundred-pound bombs that hung in their racks. The bombs looked thick and harmless. Charlie stopped while Andy shook a bomb to ensure that it had been hung securely. Andy counted the steel pins that kept the arming propeller at the tail of the bombs from spinning. They were all there. Once under way over the Channel, Andy would pull the pins and arm the bombs. Charlie found it amusing that such a meek man controlled so much destruction. Andy gave him a thumbs-up and departed to his place in the nose.

Charlie shimmied sideways along the catwalk, past the bombs and out of the bomb bay. He entered “the office” of the bomber, the cockpit. Passing beneath Frenchy’s top turret, Charlie saw Frenchy ahead of him, performing his flight engineer duties and checking the five yellow oxygen tanks on the wall behind the pilot’s seat. Those bottles were the crew’s lifeblood at high altitude, along with three behind Pinky’s seat, seven under the cockpit, and three in the floor of the radio room. Each man would plug his mask into that one system and only use portable bottles when he had to move about.

Instead of getting in Frenchy’s way, Charlie went to check on the boys in the nose. He lowered his feet down through the hatch in the cockpit floor and crawled on his knees up to the nose compartment.

Against the left bulkhead, Doc huddled over his desk and checked his compass beneath the light of a metal lamp. Seeing Charlie, he gave him a hand-sketched map he had made of the approximate headings and distances that Charlie should fly, just in case the intercom conked out. As a navigator, Doc was meticulous. He also kept the crew’s logbook and doubled as a gunner. His .50-caliber stuck out from a window ahead of his desk, and a cord dangled from the ceiling to hold its grips level.

Andy fiddled with a gun of his own opposite Doc’s. A third gun

dangled in the Plexiglas nose blister, a smaller, .30-caliber weapon that the mechanics had added as a field modification. Charlie knew Doc would claim that gun, too, and Andy would not object. Andy was a trained bombardier, but aboard

The Pub

he lacked a bombsight. Not all bombers had one, usually just the lead planes. When the lead bombardier dropped, the others behind him knew to drop. Andy’s role in “precision, daylight bombing” was that simple. “Precision” was actually a loose term. When one plane aimed and the others dropped blindly, bombs could fall only so “precisely.” The 8th Air Force measured error in hundreds of yards and even miles.

*

The Germans on the ground measured that same error in city blocks and civilian casualties. At that time in the war, 54 percent of the 8th Air Force’s bombs were landing within five city blocks of their targets. The other 46 percent fell where they were not supposed to. But one thing could be said for the American bombing method. The 8th Air Force always aimed at military targets, even if that target was nestled in the midst of a city. The 8th Air Force’s commander, General Ira Eaker, had said, “We must never allow the record of this war to convict us of throwing the strategic bomber at the man in the street.”

5

Error and all, the American bombing method could not have been more different from the common British bombing method. Due to the unrestricted manner in which the British and Germans bombed each other, British Bomber Command often practiced “area bombing,” or scattering their bombs across swaths of German cities. This destroyed more than just German war production. Sir Arthur Harris, Bomber Command’s leader, once explained the difference: “When you [the 8th Air Force] destroy a fighter factory it takes the Germans six weeks to replace it. When I kill a workman it takes twenty-one years to replace him.”

6

Charlie settled into his seat, the place he would remain for seven to eight hours or more, depending on head or tail winds. He found Pinky waiting for him, munching his candy bar. Charlie suspected that Pinky probably had a few extra squirreled away for the ride home. On Charlie’s “introductory mission,” the veteran pilot had told him to always take a “panic pee” prior to boarding, because there was seldom an opportunity to use the relief tube in the bomb bay that funneled urine outside the plane. That day, Charlie had been so full of nervous energy he’d forgotten the veteran’s advice.

In the other planes in the cloverleaf, Charlie knew their crews were strapping in. The sun was rising, and he could see the goggles on the foreheads of the other pilots who studied their instruments.

Charlie and Pinky ran through their checklist until a sound drew their attention to the end of the field. Preston’s bomber was cranking over, coming to life, telling everyone, “Gentlemen, start your engines.” In no particular order, the bombers began lighting up their engines, creating a patchwork of sound that sprung from random cloverleafs. The cacophony was powerful. The air buzzed with electricity. Pinky squirmed in his seat. Charlie tried not to smile. He had been training for two years for this moment. He had a crew he trusted, a bulletproof commander named Mighty Mo, and after his introductory mission he had come to believe that the air war was not half as scary as his imagination.

“Clear left,” Charlie said, having peeked out his left window to make sure the ground crewmen were standing away from the prop. Pinky looked out his window and announced, “Clear right.” They turned a selector switch to “Engine 1” and energized the first engine. While Pinky held the starter button and pumped primer gas into the engine, Charlie turned a switch and the Pratt & Whitney came to life with a

wheeze, cough, cough, cough

as all cylinders began popping. A white cloud sputtered from the engine, and the propeller blew it beneath the wing and across silver grass that the prop wash flattened. Charlie and Pinky ignited the other three engines, adding their share to the combined noise of eighty-four engines that promised to wake every soul across the English isle.