A History Maker

Authors: Alasdair Gray

“

Economics:

Old Greek word for the art of keeping a home weatherproof and supplied with what the householders need. For at least three centuries this word was used by British rulers and their advisers to mean

political

housekeeping â the art of keeping their bankers, brokers and rich supporters well supplied with money, often by impoverishing other householders. They used the Greek instead of the English word because it mystified folk who had not been taught at wealthy schools. The rhetoric of plutocratic bosses needed

economics

as the sermons of religious ones needed The Will of God.”

â from

The Intelligence Archive of

Historical Jargon.

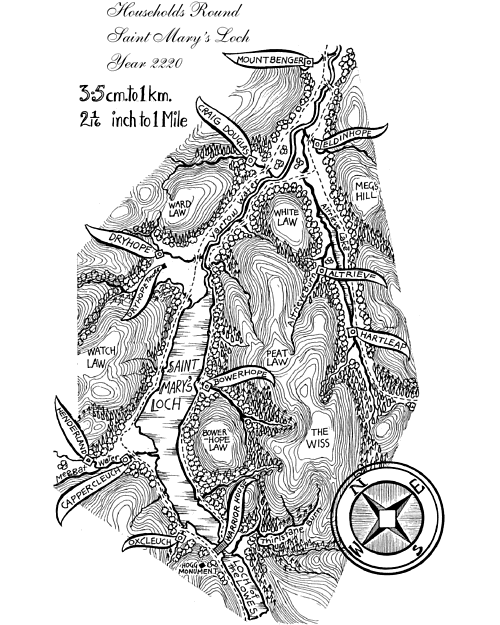

Map of Saint Mary's Loch, 2220

TITLE PAGE

and

DEDICATION

Book Information

EPIGRAPH

TABLE of CONTENTS

CHAPTER Two â Private Houses

CHAPTER Three â Warrior Work

Postscript by a Student of Folklore

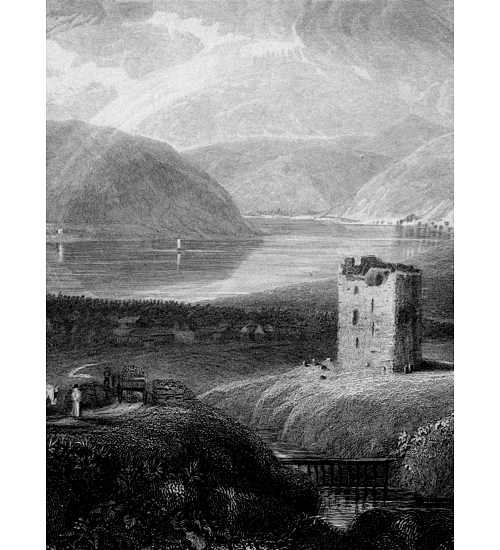

Dryhope Tower Â

and Saint Mary's Loch, Â

Bowerhope to the left on the far shore, Â

around 1822Â

BEFORE VANISHING from the open

intelligence net Wat Dryhope gave me a

printout of the next five chapters saying, “My

apology for a botched life, mother. Do what

you like with it.”

I put it on a shelf behind old encyclopædias.

The title scunnered me. Not knowing it was

ironical I feared that his memoirs, like those

of ancient politicians, would hoist a claim

to importance by blaming his failure on

wicked enemies and stupid helpers. The

words “a botched life” suggested something

different but equally dreich: the start of

Augustine's Confessions where the saint

prepares us for his extraordinary conversion

by denouncing his very ordinary early

nastiness. I loved Wat most of my gets so

had no wish to read what might make me

despise him. Nor could I burn his writing

unread. I placed it in easy reach and ignored

it for years

.

Â

One grey dank autumn afternoon two

months ago I had fed the poultry and was

snibbing the henrun gate when I fell down

flat and took an hour to regain breath and

balance. I have had several tumbles lately,

each worse than the last; have also started

recalling events of twenty, forty, sixty years

ago more clearly than this morning or

yesterday. Lying on the cold ground I knew

that if not killed by a stroke I must soon join

my daughters softening into senile dementia

in the house where I was born. On returning

to the tower I took Wat's printout from the

shelf and dusted it. After filling a glass with

uisge beatha I began to read and finished

long before nightfall without sipping a drop.

Admiration for Wat had become my strongest

feeling; also anger with myself for keeping

his work so long from the public. Later

readings have not lessened my admiration

for the clarity of the narration and honesty

of the narrator.

Â

A History Maker

tells of seven crucial

days in the life of a man with all the

weaknesses that nearly brought the matriarchy

of early modern time to a bad end yet

all the strengths that helped it survive,

reform, improve. Wat Dryhope, like Julius

Caesar describing his Gallic wars, avoids

vainglory and self-pity by naming himself

in the third person and keeping the tale

factual. He also writes so cannily that, like

Walter Scott in his best novels, he gives the

reader a sense of being at mighty doings.

Adroit critics will notice his sly shift from

present to past tense in the first chapter. Like

Scott he tells a Scottish story in an English

easily understood by other parts of the world

but leaves the gab of the locals in its native

doric. This shows he wanted his story read

inside AND outside the Ettrick Forest, and

I have warstled to help this by putting

among my final notes a glossary of words

liable to ramfeezle Sassenachs, North

Americans and others with their own variety

of English

.

Â

Yet with all its art four fifths of Wat's story

is proven fact on the testimony of a whole

horde of independent witnesses. The first

chapter is not only confirmed by public eye

records but clearly based on them. These

records also confirm his account of the

reception before the Ettrick Warrior house,

his platform announcement, his talk with

Archie Crook Cot in the third chapter, and

quotations from public reports and discussions

of the new militarism in the fifth. Open

intelligence archives confirm the judgement

on the EttrickâNorthumberland cliffside

battle by the Council for War Regulation

Sitting in Geneva, and the night of puddock

migrations to fresh water in southern

Scotland that year, and the dates and

wording of the advert and banquet invitation

issued by Cellini's Cloud Circus

.

Â

I have also sent copies of

A History Maker

to everyone I could find who is mentioned

in it. Only Mirren Craig Douglas (that bitter

woman) returned it without comment, which

from her must signify assent. Wat's brothers

Joe and Sandy â his mistresses Nan and

Annie and the Bowerhope twins â the

veterans and servants of the Warrior house

â the sisters who nursed him â I who

schooled him â General Shafto who took

him to the circus â all say he tells the truth

as they recall it. Only the account of his

doings with Meg Mountbenger in the

gruesome fourth chapter are not confirmed

by another protagonist, and why should he

turn fanciful about her when honest about

others? Some critics say Lawrence's account

of his rape in

The Seven Pillars of Wisdom

is

an invention by which a lonely masochist

got public sympathy for his queerness.

Perhaps. Nothing else in Lawrence's story

depends on that rape so he may or may not

have tholed it. But after Wat left Bowerhope

that morning only a sore carnal collision

can explain his state when he was found

by the loch side, and explain his remarks to

his sisters, and his story to me, and his

dissemination of a plague which withered

powerplants in every continent but

Antarctica. If still alive Meg is sixty-three.

Should she reappear and deny Wat's story

let none believe her. She was always a

perverse bitch. She was the first of my gets,

but I never liked her

.

Â

So I bequeath

A History Maker

to the

open intelligence, having added to the end

notes explaining what those who ken little

of the past may find bumbazing. For

posterity's sake my notes about the

immediate present are put in the past tense

too, since the present soon will be. Wat was

a scholar and a fighter. His tale of warfare,

love and skulduggery also meditates on

human change. It antidotes a dangerous

easy-oasy habit of thinking the modern world

at last a safe place, of thinking the past a

midden too foul to steep our brains in. Last

week a Dryhope auntie asked me, “Why

remember those nasty centuries when honest

folk were queered, pestered and malagroozed

by clanjamfries of greedy gangsters who

called themselves governments and stock

exchanges? I wouldnae give them

headroom

.”

Â

This wish not to see how we got here is

ancient, not modern. Over three hundred

years ago Henry Ford said, “History is

bunk.” He was a practical genius who

changed millions of lives by paying folk to

make carriages in big new factories, while

getting millions more to sell and buy

carriages these factories made. Having

mastered the new art of industrial growth

he thought intelligent life needed nothing

else. By 1929 the big new factories had made

more carriages than could be sold at a profit.

The owners closed the factories, millions of

makers lost their jobs and houses, and even

some rich folk suffered. Ford, not seeing that

his method of making money had produced

this poverty, blamed the collapse of industrial

housekeeping on Communists and Jews and

said Adolf Hitler's fascism was the cure. He

was partly right. The Second World War let

him expand his factories again for he used

them to make machines for the American

armed forces. He was not nasty or stupid by

nature, but ignorance of the past fogged his

view of the present and blinded him to the

future

.

Â

A History Maker

shows that good states

change as inevitably as bad ones, and should

be carefully watched. My pedantical lang-nebbed

notes at the end try to emphasize that.

They also emulate my son's modesty by

naming me in the third person. If any future

reader learns what happened to my brave,

discontented, kindly, misguided, long-lost

son I hope he or she will add a postscript for

the satisfaction of posterity. I am sorry that

I will not be here to read it

.

Â

Kate Dryhope

Â

Dryhope Tower

Â

8 December 2234

Â