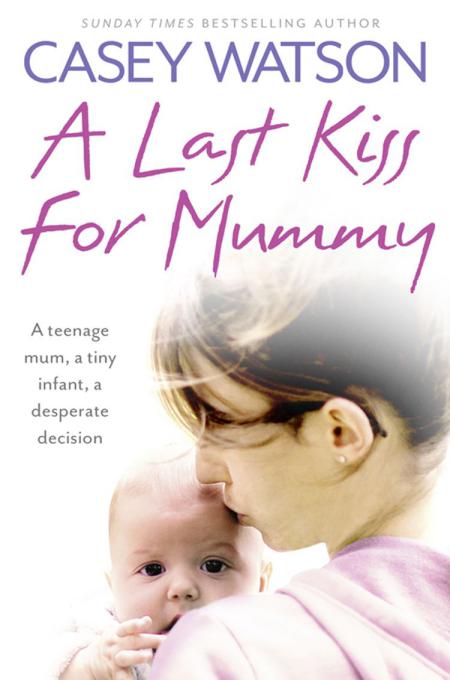

A Last Kiss for Mummy

Read A Last Kiss for Mummy Online

Authors: Casey Watson

To my wonderful and supportive family

I would like to thank all of the team at HarperCollins, the lovely Andrew Lownie, and my friend and mentor, Lynne.

I’ve known my fostering link worker, John Fulshaw, for something approaching seven years now, so I’ve got to know his face pretty well. I’ve seen his happy face, his sad face, his ‘I don’t know how to tell you what I’m about to tell you’ face, his concerned face, his angry face and his ‘Don’t worry, I’ve got your back’ face as well.

So there wasn’t much that got past me, and today was no exception. There’d been this glint in his eye since the start of our meeting; a glint that told me that today he was wearing his ‘I can’t wait to tell you’ face. He’d had ants in his pants since he’d arrived.

It was a chilly autumn morning at the end of October. Not quite cold enough to put the heating on mid-morning, but certainly cold enough for me to be wearing my standard winter months outfit of leggings, a fluffy jumper and boots. My husband Mike had taken a rare day off from his job as a warehouse manager, and we were all grouped around the dining table, drinking coffee and trying to avoid eating too many biscuits, because it was the day we had our annual review.

It’s something all foster carers have, as a part of what we do – a summing up of how things have gone during the previous year. It’s a time to look back to previous placements, discuss what went well and what didn’t, talk about any complaints and allegations (none for us, thankfully) and, if appropriate, talk about what new things might happen in the coming year. It’s also an opportunity to discuss further training. As specialist foster carers we usually attend at least three training courses per year. In our case, today, everything had been positive, thank goodness. Not every placement works out well – that’s the nature of the job – but we had had a good year and Dawn Foster, the reviewing officer, who was also present, had praised me and Mike for the way we’d handled our last placement: two unrelated nine-year-old boys. Both had certainly been in need of support. Jenson was somewhat wayward, being the child of a neglectful single mother – one who’d left him and his sister home alone while going off on holiday with her boyfriend for a week. Georgie’s problems were different. He was autistic and had come from a children’s home that was closing down; the place where he’d spent almost all of his young life. Individually, both boys came with their own challenges, but our biggest challenge was that we’d had them both together. It had been a rocky ride at times, but, thankfully, they ended up friends.

The review over, and with Dawn on her way back to the office, I closed the front door with a now familiar tingle. We were between placements at the moment and the warm glow I’d felt when Dawn had been singing our praises had now been replaced with a feeling I knew all too well; one of excited anticipation. Just why did John have those ants in his pants? At last I’d have a chance to find out.

When I went back into the dining room – well, dining area, actually; the downstairs of our house is open plan – John was grinning and rubbing his hands together.

‘Well?’ I asked. Mike looked at me quizzically, but John laughed.

‘Get the kettle back on then,’ he said, his eyes glinting mischievously, ‘and I’ll tell you what I’ve been dying to tell you for the last hour.’

By the time I got back, of course, the pair of them were both grinning like idiots, so it was clear Mike was now one step ahead of me. I set the tray down and took my place back at the dining table. ‘Come on then,’ I said, plonking both elbows down. ‘Spit it out.’

Mike laughed, seeing my expression. ‘I think you’d better, John.’

John took his time, picking up his mug and taking a first sip of fresh coffee. ‘Actually, it’s not so much a “tell” as something I want to run by you.’

Which was always ominous. John had a history of wanting to ‘run things by’ us. It invariably meant he wasn’t confident that it was something we’d say yes to – at least wouldn’t say yes to if we had any sense. But that never fazed us. We had never been trained to do mainstream fostering. We were specialists – we specialised in taking the sort of kids that were too damaged or disturbed, for whatever reason, to be suitable for mainstream fostering or adoption.

So what would it be today? I raised my eyebrows enquiringly. ‘So, Casey,’ John said, speaking mostly to me now. It was me, after all, who’d do the day-to-day childcare. We fostered together but Mike obviously had his full-time job as well.

‘Yes,’ I said eagerly.

‘Well, it’s this,’ he said. ‘Have you ever considered a mother and baby placement?’

I caught my breath. No, I hadn’t. It had never even occurred to me. A baby was hardly likely to be damaged at such a tender age, after all. On the other hand, what about the mother? My mind leapt ahead. A baby! I adored babies. Always had. Everyone knew just how besotted I was with my own two grandsons, Levi and Jackson. ‘What do you mean, exactly?’ I thought to ask then. ‘A mother and a baby, or a young pregnant girl?’

John grinned. He could read my expressions just as easily as I could read his. And mine currently had the word ‘baby’ flashing up in neon on my forehead. He knew how fond I was of saying how much I could almost eat my little grandsons, so it was odds on my interest would be piqued.

‘Good point,’ he said. ‘You’ve obviously read the handbook very thoroughly, because you’re right; a mother and baby placement can be either. But in this case, an actual baby. The mum, Emma, is just fourteen and baby Roman is three weeks old.’

‘Oh!’ I cooed. ‘Roman! What a lovely name she’s chosen!’ I turned to Mike. ‘Oh, please, we must. Oh, imagine having a new baby in the house. It would be great.’

‘Slow down, love,’ Mike warned, as I’d already known he would. That was the way it worked with us – I was all enthused and optimistic, whereas Mike was more reticent, always considering potential pitfalls. As systems went, it was a good one, because though more often than not I got my way, it at least meant I rushed into things slightly better informed than I would have been if left to my usual impetuous devices.

He turned to John now. ‘Did she have the baby in care?’ he wanted to know. ‘Or is she just coming into the system?’

‘Good question,’ John said. ‘And you’re right to be cautious, Mike. Emma has been in and out of care for most of her life. Her mother swings between periods of calm and what seems to be pretty “difficult” behaviour. It’s a familiar story, sadly. The mum is alcohol and drug dependent most of the time, and suffers from depression too – cause and effect? – though she does go through periods of drying out now and again. She’s a single parent, and Emma is her only child. When she’s clean she always wants to have Emma back living with her again – which is what Emma usually wants, too – but it’s never too long before the depression takes over again, and then the drinking starts and the poor kid is scooted back into the care of social services quick-smart.’

The atmosphere in the room changed. That was all part of the process; going from asking all about a new child who needed us, to the sober contemplation of just how that state of affairs had come about. The baby, for the moment, was forgotten, as my heart went out to his mother – this poor fourteen-year-old girl who I didn’t yet know. I took a moment, even though I knew we would have to take her in. I mustn’t let Mike and John think I was jumping in too quickly and not taking time to assess the situation properly. I tried to hide my growing excitement (and it was excitement, no question) as I turned and spoke to John.

‘So what’s the situation?’ I asked. ‘Any boy in the background who is willing to take responsibility?’

John reached into his briefcase and took out a by now familiar buff-coloured file. Popping on his reading glasses he then flicked through some pages. ‘Yes and no,’ he said. ‘It’s complicated. What happened,’ he glanced up, ‘well, according to the mother, anyway, is that Emma had started running a bit wild and next thing was that she found herself pregnant. She’d been back living at home again for almost a year by this time – a pretty longish stretch, given the history. Anyway, when the mother found out about the pregnancy she insisted Emma have an abortion, but Emma apparently refused. At that point the mother washed her hands of her completely, and threw her out, apparently thinking that in doing so she might make Emma come to her senses.’

Mike frowned. ‘So not out of character at all, then,’ he muttered drily. And I tended to agree with him. Could I ever imagine throwing my teenage pregnant daughter out on the street just to make her ‘come to her senses’? Not in a million years. I couldn’t think of a more perfectly designed recipe for disaster. But then, I wasn’t her, was I? And drink, drugs and depression affected a person in all sorts of dangerous ways.

‘Well, exactly,’ John agreed. ‘And of course, the abortion didn’t happen, and since that time Emma’s been staying with various friends, mostly with another girl – a friend who lives on the same estate, with her single mum. That’s where she is now. But since the baby was born just over three weeks ago, the girl’s mum’s apparently said she can’t afford to keep both Emma and Roman, and that’s the point when Emma’s mum finally got in touch with social services.’

‘To put her straight back into care again,’ I said. It wasn’t a question. Just a sad, all too familiar statement of fact: she obviously didn’t want either daughter or grandchild back at home with her, presumably as the lesson hadn’t been learned. ‘What about the boyfriend, then?’ I went on, thinking what a desperate situation it was for a baby to be born into. ‘There’d be some police involvement, wouldn’t there, given that she’s under age?’

John paused to sip some coffee. ‘As I say, it’s complicated. And here’s the stinger; we and just about everyone else, apparently, believe the father is a nineteen-year-old drug dealer, name of Tarim. Emma had been seeing him for some time, it seems, though she has always denied that he’s the father.’

‘As I suppose she would,’ Mike said, ‘if she didn’t want to get him into trouble.’

John smiled wryly. ‘Which he already is. He’s in prison right now, doing time for dealing. Went down while she was still pregnant. He has previous form, apparently – so has not been on the scene at all. And though Emma’s adamant he’s not the father, the woman she’s been staying with is absolutely convinced he is. The baby is the spit of him, apparently. Though of course they want the relationship discouraged, just as much as Emma’s mother does, saying he’s no good for her –’

I shook my head. ‘Really?’ I said wryly. ‘Whatever makes her think that?’

John nodded and closed the file. ‘Quite, Casey. So that’s where we’re at. And it’s a lot to think about so I do want you both to have a think.’

So no plunging in feet first, as I usually liked to do, then. And John was right to tell us to think because it was a great deal to take on. A newborn baby on its own would be a big physical challenge – babies were exhausting, full stop, for anyone. But to take on a newborn and a teen mum – one barely even into her teens in this case – would add a whole other layer of complication. She’d have her issues – how could she not, given her upbringing and current circumstances? – not to mention the ever-present spectre of having her baby taken away from her if she couldn’t prove she was able to look after it. And what about this mum of hers? What might happen there? Much as I couldn’t personally get my head round the idea of throwing out my own daughter and grandson, I wasn’t naïve either. This was a woman with a long history of substance abuse and mental illness, which meant all bets were off as far as good parenting manuals were concerned. The poor girl. What a mess to bring a new life into. She must be reeling and terrified, the little mite.

I glanced at Mike, who was deep in thought as well. I could tell. I met his eye, wondering if he was thinking what I was – that we had to find a way to make this work.

‘Look,’ said John, ‘don’t rush into this. It’s a huge undertaking and I would absolutely understand if you didn’t feel it was for you. After all, most mother and baby carers go through a specific course of training …’

‘I’ve had two children,’ I chipped in, ‘both fully grown now, not to mention two grandchildren, not to mention eight foster kids and counting … it

is

eight, isn’t it, Mike?’ I started pretending to count on my fingers.

John smiled at me. ‘I’m

serious

, Casey. This is a complicated placement. With a great deal of potential for getting even more complicated, as I’m sure you realise all too well. Look, you know why I’m putting this to you. It’s because I think the two of you could handle it. Of course I do. But I still have to talk it through with Emma’s social worker anyway. Plus the baby’s – he’ll obviously be allocated his own social worker, if he hasn’t been already. Which’ll give you two time to discuss it –’ he pushed the buff folder across the table to us. ‘To read up properly, to consider the implications and think it through before committing. A new baby affects everything, as you both know all too well. Means changing plans, not booking holidays, having your whole routine thrown into disarray …’

‘Well,’ said Mike, his positive tone of voice making my heart leap. ‘It certainly does sound like something we should consider. But as you say,’ he said, looking pointedly at me, ‘we do need to weigh it up properly. Can you give us a day or so?’

John nodded as he rose from the table. ‘Absolutely. As I say, I have to talk things through with the social workers anyway. And no doubt you’ll want to have a chat with the rest of the clan, too.’

Which we would. The clan in question mainly being our daughter Riley and her partner David. If we were talking baby stuff, I doubted we’d be able to keep Riley away. She loved babies as much as I did, loved to immerse herself in children generally, and was also keen to help out whenever she could when we were fostering, because she and David had just finished the training to become foster carers themselves. We’d obviously also need to speak to our son Kieron. Though he no longer lived at home – he shared a flat with his long-term girlfriend Lauren – we never did anything that would impact on any member of the family without consulting them first. It wouldn’t have been fair. Because John was right, having a new baby in the mix would change everything. Which would obviously affect everyone else.