A Little History of Literature (22 page)

Read A Little History of Literature Online

Authors: John Sutherland

Unusual for his times, Tennyson lived to over eighty, two decades longer than Dickens, five decades longer than Keats. What might they have done with those Tennysonian years?

Tennyson published his first volume of poems when he was just twenty-two. It contained what are still many of his best-known lyrics, such as ‘Mariana’. Alfred regarded himself at this period as very much a Romantic poet – the heir to Keats. But Romanticism, as a vital literary movement, had faded by the 1830s. No one wanted warmed-over Keats. There ensued a long fallow period in his career – the ‘lost decade’, critics call it. It was a period in the wilderness. He broke out of this paralysis and in 1850, aged forty-one, produced the most famous poem of the Victorian period –

In Memoriam A.H.H.

It was inspired by the death of his best friend, Arthur Henry Hallam, with whom, it is speculated, his relationship was so intense it might have been sexual. It probably wasn't, but intense, in the kind of ‘manly’ way approved by Victorians, it certainly was.

The poem is made up of short lyrics, chronicling seventeen years of bereavement. The Victorians mourned the death of a loved one for a full year – in dark clothes, and with black edged notepaper; women wore veils and specially sombre personal jewellery. In this mournful poem Tennyson meditated on the problems that most tormented his age. Religious doubt afflicted the second half of the nineteenth century like a moral disease. Tennyson was afflicted even more than most. If there was a heaven, why did we not rejoice when someone dear to us died and went there? They were going to a better place. But

In Memoriam

remains essentially a poem about personal grief. And finally, the poem concludes, despite all the pain, ‘'Tis better to have loved and lost /Than never to have loved at all’. Who, having lost a loved one, would wish they had never existed?

Queen Victoria lost her beloved consort, Albert, to typhoid, in 1861. She wore ‘widow's weeds’ until the end of her life forty years later. She confided that she found great consolation in Mr Tennyson's elegy for his dead friend, and on the strength of it the two, poet and queen, became mutual admirers. Tennyson was not

just a Victorian poet – he was

Victoria's

poet. Appointed her poet laureate in 1850, he would hold the post until his death, forty-two years later.

The great enterprise of his later years was a massive poem on the nature of ideal English monarchy,

Idylls of the King

, a chronicle in verse of the reign of Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. It was, clearly, an indirect tribute to the English monarchy. Tennyson wrote, as all poet laureates do (even the dynamic Ted Hughes when he held the post from 1984), some very dull stuff. But he also wrote, as poet laureate, some of the finest public poems in English literature, most notably ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’ (1854), commemorating a bloody and absolutely hopeless assault by some 600 British cavalry on Russian artillery guns, during the Crimean War. The casualties were huge. A French general watching said, ‘It is magnificent, but it is not war’. Tennyson, who read the account of the engagement in

The Times

, came up with a poem, written at great speed, which catches the thundering hooves, the blood, and the ‘magnificent madness’ of it all:

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon behind them

Volley'd and thunder'd;

Storm'd at with shot and shell,

While horse and hero fell,

They that had fought so well

Came thro' the jaws of Death

Back from the mouth of Hell,

All that was left of them,

Left of six hundred.

In his later years, Tennyson played the part of poet majestically, with flowing hair, a luxurious beard and moustache, and a Spanish cape and hat. But beneath the costume and the pose, Tennyson was the most businesslike of authors, as keen as the next man for money and status. He rose to the top of the slipperiest of literary

poles to die Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and richer, from his verse, than any poet in the annals of English literature.

Did he sell out, or was it a finely judged balancing act? Many who care about poetry see a Victorian contemporary, Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–89), as a ‘truer’ kind of poet. Hopkins was a Jesuit priest who wrote poetry in what little spare time he had. It has been said that his only connection with Victorian England was that he drew breath in it. Hopkins admired Tennyson, but he felt his poetry was what he called ‘Parnassian’ (Parnassus being the poets' mountain in ancient Greece). Bluntly, he felt that Tennyson had surrendered too much by ‘going public’. Hopkins himself would rather have died than publish a poem like

In Memoriam

for any man or woman in the street to pore over his grief.

Hopkins burned many of his highly experimental poems. His so-called ‘terrible sonnets’, in which he struggled with religious doubt, are intensely private. He probably never intended anyone other than his closest friend, Robert Bridges, to see them. Bridges (destined, ironically, to become poet laureate himself in 1913) decided, almost thirty years later, to publish the poems Hopkins had entrusted to him. They are regarded as pioneer works of what would, a few years after his death, be called modernism, and change the course of English poetry.

So who, then, was the truer poet, ‘public’ Tennyson or ‘private’ Hopkins? Poetry has always been able to find room for both kinds.

CHAPTER

23

New Lands

A

MERICA AND THE

A

MERICAN

V

OICE

One of the insults that used to be directed at American literature by outsiders was that it didn't exist – there was only English literature written in America. It's ignorant as well as insulting and, not to waste words, plain wrong. George Bernard Shaw commented that ‘England and America are two nations divided by a common language’. It is true of the literature of all different English-speaking nations, but especially true in this case. There is, whatever the fuzzy edges, an American literature as rich and great as any literature anywhere, or that there has ever been in any period in recorded history. It helps to characterise the nature of that literature by looking at its long history and considering some of its masterpieces.

The starting point of American literature is Anne Bradstreet (1612–72). Every anthology bears witness to the fact. All American literature, said the modern poet John Berryman, pays ‘homage to Mistress Bradstreet’. It marks a difference between British and American literature that in the New World the founding figure is a woman. No one ever said English literature started with Aphra Behn.

Mistress Bradstreet was born and educated in England. Her family was part of the Puritan ‘Great Migration’ – under religious persecution – to the place they called ‘New England’, the Eastern seaboard of America. Anne was sixteen when she married, and undertook the voyage two years later, never to return. Both her father and her husband would go on to be governors of Massachusetts. While the men of the family were off governing, Anne was charged with running the family farm. She evidently did it well. But she was much more than a competent farmer's wife and the mother of their many children.

The enlightened Puritans believed that daughters should be as well educated as sons. Anne was intelligent, extraordinarily well read (her contemporary Metaphysicals were of particular interest – see Chapter 9), and was herself an ambitious writer, something which was not frowned upon by her Puritan community, as it might perhaps have been in England. She wrote vast amounts of poetry, but as a spiritual exercise, an act of devotion, rather than for any fame, current or posthumous. Her best poems are short; her life was too busy for long works. Her brother, recognising her genius and the originality of her mind, made heroic efforts to get her verse published in England. There was, as yet, no ‘book world’ in the American colonies.

Despite their self-imposed exile, the Puritans felt an unbreakable bond with the Old Country – hence placenames like ‘New’ England or ‘New’ York, but there was also a strong sense of permanent spiritual separation. Anne Bradstreet's poems are quintessentially of the New World, as the Puritans saw America and their place in it. Take, for example, her poignant ‘Verses upon the Burning of Our House July 10th, 1666’:

I blest His name that gave and took,

That laid my goods now in the dust.

Yea, so it was, and so 'twas just.

It was His own, it was not mine …

The poem concludes, poignantly,

The world no longer let me love,

My hope and treasure lies above.

It's a traditional Puritan sentiment – this world is of no real consequence: what matters is the world to come. But what we hear in the verse is an entirely new voice – an American voice, moreover the voice of an American ‘making’ the new country. Anne and her husband had built that house that now lay in ashes. They would, of course rebuild. America is a country constantly rebuilding itself.

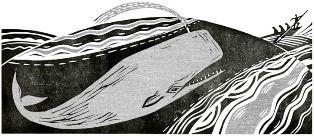

Puritanism is a foundation stone of American literature. It flowered as literature in the work of the so-called Transcendentalists of New England in the nineteenth century – writers such as Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Transcendentalism is a big word for what was essentially the faith of the early colonials – that the truths of life are ‘above’ things as they appear in the everyday world. Melville's

Moby-Dick

(1851), chronicling Captain Ahab's hunt for the great white whale, is routinely cited as an archetypally American novel. What makes it that? The sense of endless quest, the pacification (even if it means the destruction) of nature, and the voracious appetite for natural resources to fuel this ever growing, ever self-renewing new nation. Why were whales hunted? Not for sport. Not for food. They were hunted to the point of extinction for the oil extracted from their blubber for lighting, machinery and any number of manufacturing activities.

Walt Whitman (Chapter 21), the self-declared disciple of Emerson, embodies another aspect of the Transcendentalist tradition – its sense that ‘freedom’, in all its many facets, is the essence of all American ideology, including poetic ideology. In Whitman's case it took the form of ‘free verse’ – poetry unshackled from rhyme, just as the country itself had thrown off the shackles of colonialism in its War of Independence against the British in 1775–83.

Freedom, in America, presupposes literacy. It has always been a more literate country than Britain. The country's forging of its identity began with a document, the Declaration of Independence. In the nineteenth century America could boast the most literate

reading public in the world. But the literature that originated in the United States was somewhat stunted by the country's refusal (in the name of ‘free trade’) to sign up to international copyright regulation until 1891. Before that date, works published in Britain could be published in America, without any payment to the author. Writers like Sir Walter Scott and Dickens were ‘pirated’ in huge quantity and at budget prices. It fostered American literacy but it handicapped the local product. Why pay for some promising young writer when you could get

Pickwick Papers

free? (American plundering of his work drove Dickens to apoplectic rage – he got his own back in the American chapters of his novel

Martin Chuzzlewit

.)

This is not to say that there was no homegrown American literature at this time. The ‘great war’, according to no less an admirer than Abraham Lincoln himself, was started by Harriet Beecher Stowe with her anti-slavery novel,

Uncle Tom's Cabin

(1852). It sold by the million in the troubled mid-nineteenth century and, if it is not true that it started a war, it did change the public mind.

A powerful, unique and self-defining impulse in American literature of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is the ‘frontier thesis’ – the idea that the essential quality and worth of Americanness is most clearly demonstrated in the struggle to push civilisation westward, from ‘shining sea to shining sea’. James Fenimore Cooper, author of

The Last of the Mohicans

(1826), is one of the early writers who chronicled the great push west. Virtually every cowboy novel and film springs from the same ‘frontier thesis’ root. Where civilisation meets savagery (at it crudest, paleface meeting redskin) is where true American grit is displayed. Or so the myth goes.