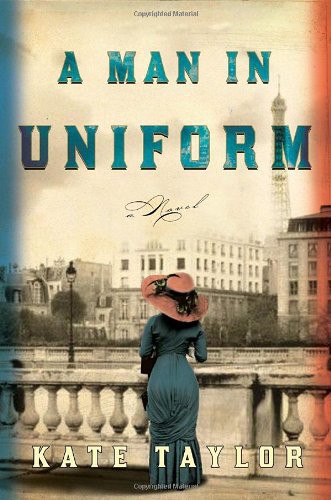

A Man in Uniform

Authors: Kate Taylor

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #General, #Biographical

Also by Kate Taylor

Madame Proust and the Kosher Kitchen

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2010 by Kate Taylor

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Originally published in Canada by Doubleday Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, Scarborough, Ontario.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Taylor, Kate, 1962–

A man in uniform: a novel / Kate Taylor. —1st ed.

1. Dreyfus, Alfred, 1859–1935—Fiction. 2. Spies—France—Fiction. 3. Treason—France—Fiction. 4. Trials (Military offenses)—France—Fiction. 5. Lawyers—France—Fiction. 6. Jews—France—Fiction. 7. Paris (France)—Fiction. I. Title.

PR9199.4.T38M36 2010

813′.6—dc22 2010017621

eISBN: 978-0-307-88521-0

v3.1

For my parents

On October 15, 1894, the French army accused Alfred Dreyfus, a captain in the artillery, of passing military secrets to the Germans. On December 22, a court martial found Dreyfus guilty of treason and sentenced him to life imprisonment.

What follows is a work of fiction.

Those who truly love justice have no right to love.

—

ALBERT CAMUS

,

The Just

There was something small—and apparently alive—at the bottom corner of the cot. The thing was scratching at his toe. In gentler circumstances, he supposed this would be irritating, or even frightening. Was it a beetle? Or worse yet a mouse? But in this long night, he found the tickling sensation on his right foot a small comfort. Here was an event to mark the undifferentiated time stretching to dawn; another creature would share his vigil.

His captors had never given him a light, simply locking him in the tin shed at dusk and unlocking the door at dawn. On moonlit nights, he could just make out the shape of the small, bare room in the pale light seeping underneath the door. Other nights, he lay in darkness so complete he had to crawl across the dirt floor, feeling his way with his hands to find the bucket into which he relieved himself. In these climes, there was little perceptible difference between the longest and shortest day of the year, and all were uniformly hot. If he was lucky, he could sleep away eight or ten hours of these twelve-hour nights, but in the rainy season, overcast days forced him inside earlier and the water pounding on the roof over his head prevented him from sleeping. He

would lie awake for what seemed like huge swaths of time, unsure if he had slept or not, confused as to whether he was at the beginning of the night or its end. Only the faint gray light from under the door could rescue him, propelling him into another day. Whatever its heat or its horrors—boredom, loneliness, humiliation—the day could not be worse than the half death of these nights in which he felt his own existence slipping away from him, drawing him down toward nothing.

The thing at the bottom of the bed seemed to have a hard shell, a carapace of sorts. He wondered now if it was a scorpion. He supposed there might be scorpions on the island, although his jailers had never mentioned the creatures, and they seldom failed to regale each other with descriptions of the local fauna. Making waving motions with their arms and hissing between their teeth, or jumping about like madmen and scratching their armpits, they would imitate the giant snakes and bands of chattering monkeys that roamed the jungles of the mainland. Although they never spoke directly to him beyond the occasional barked command or acknowledged his existence in their own conversations, these displays were surely aimed at him. These were the creatures that would drive him insane or kill him outright if he ever managed to reach the other side of a strait patrolled by sharks and piranha. “Care for a swim?” the guards would sometimes ask laughingly of each other, when they caught him looking out to the sea beyond his hut. His captors had no need of a fence to keep him here.

The thing was beginning to crawl up the leg of the loose canvas trousers he wore day and night. Perhaps it

was

a scorpion. Was its venom lethal? On some nights, he might have desperately hoped so, but tonight he could not even muster a death wish. The thing crawled a little higher. He finally shook his right leg and brushed it off with his other foot. There was a small noise as it fell to the floor and scuttled away.

Some time later, an hour or two as best he could judge, morning was announced not by light under the door but by voices outside the shed. Men working, apparently, giving each other instructions, digging, he gathered from the clang of a shovel against rock. Soon after, his door was opened and his breakfast—hard bread and a cup of water—was placed on the floor. He struggled to his feet. This morning his

guard was the lieutenant, an unbending young man never given to the crude jokes and mocking insults of the others.

“You’ll stay in here today,” the lieutenant announced, “until the work is done.”

He slumped back onto his cot. He had never stayed inside the shed on a dry day before; only the most ferocious storms could keep him here. Usually, he sat outdoors, with the overhang of the shed’s roof providing either shade from the sun or shelter from the rain. He had been given a battered cane chair and table when he arrived, and eventually was permitted pen and paper. It had seemed a great breakthrough and, at first, he had written long letters home. More recently, he didn’t bother, but simply sat and stared at the sea. He had also talked to himself, just to hear a human voice in the long hours of solitude, but now he didn’t do that either, and when he tried to use his voice he found it was little more than a croak.

The men dug for much of the morning. They were convicts too, he concluded from the shouts directed at them. A gang must have been brought over from one of the other islands. They complained of the heat and called for water, but he supposed his windowless tin shed was worse. The heat was now becoming more than he could bear. The sides of the shed were burning hot. He lay in the middle of the room to avoid brushing against the metal. If he pressed his face to the floor, the dirt seemed slightly cooler than the air.

After a while, the digging stopped. It was replaced by some slower work, something heavy being moved about. There were cries of “Steady, steady!” or “Hold it!” but he couldn’t figure out what the men were doing. It grew hotter still, and eventually the work stopped. The door opened. He looked up from the floor. The lieutenant had brought him another cup of water, but when he tried to stand he fell back. The lieutenant crouched and put the cup to his lips. After a sip or two, he downed the rest greedily. He tried to ask for more, but the sound that escaped his mouth was barely a whisper. The lieutenant said nothing and left. He fell back to the floor, despairing, but the man returned a few minutes later with a whole jug. It was the only time he recalled the lieutenant showing compassion.

Later, it seemed to grow cooler, or perhaps it was just the water

inside him. The work had started again. The half light in the interior of the shed was growing fainter now. The work stopped. The lieutenant returned and held the door open. “Out.”

He staggered out. It was almost dusk. There was no sign of the convicts but their work was evident. They were building a rough wooden palisade around the tin shed. Only one of the four sides, the front, was complete, but it presented a solid wooden wall. He could no longer see the sea.

Maître Dubon lifted his gaze from Madeleine’s right breast, which was peeking out tantalizingly from under a crisp white sheet, and let it travel slowly down the bed, admiring as he did so how the draped cotton clung to her body in some places and obscured it in others. He glanced across the room and let his eye come to rest, ever so casually, on the ornate gilt clock that sat atop the dresser. It was twenty minutes before the hour.

“Well, perhaps it’s time we get dressed.” Still leaning back against the pillows, he waited a long moment before he made up his mind to move, and then took the plunge, pulling the sheet off his own body, swinging his feet to the floor and standing.

Beside him, Madeleine stirred and stretched an arm languidly across the bed toward an armchair. Dubon crossed over to it, picked up the peignoir that was lying there, and held it open for her. As she rose to her feet, she slipped her arms into it, drawing the fluttering layers of its wide lace collar over her shoulders and around her neck. He moved to his clothes, pulling on his undershirt, shirt, pants, and waistcoat, buttoning buttons as he did so, methodically but with no apparent

haste. He turned to a full-length mirror that stood in one corner of the room and straightened his tie approvingly. Though only of average height, he had a big head, and a finely shaped nose, straight but for the sharp break that formed a little shelf at the bridge, and his features gave him presence. His hair was still good and thick, he always noted with pleasure, and the occasional strand of silver that now appeared at the temples added an air of distinction.