A Manual for Creating Atheists (31 page)

Read A Manual for Creating Atheists Online

Authors: Peter Boghossian

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First and foremost, thanks to my wife. I could never have done this without her tireless support. She is my rock. She is my place of safety in chaos. Thanks to my daughter for her patience and to my son for allowing me to bounce ideas off of him. Thanks to my mother and father for a lifetime of kindness, generosity, and unconditional love. Mom, you were my best friend. You are missed beyond measure: your grace, humor, compassion, irreverence, and unconditional love are models I strive to emulate. My goal is to do for my children what you have done for me. Thank you for sharing your life with me. I love you and will always love you.

Thank you Jason Stevens and Matthew Hernandez for exceptional research contributions. (Jason was literally an atheist in a foxhole.) Jason and Matthew worked diligently in helping me fact-check, cite, and research sometimes obscure topics. Ryan Marquez, Renee Barnett, and Anna Wilson also helped me hammer out and research important details. Thanks to Corey Van Hoosen for creating the front cover and illustration in appendix C. (Corey [

[email protected]

] also makes the custom images for my presentations.) Thank you to my childhood friend and amateur historian Jimmy Farrell for helping me with footnote 12 in chapter 7, and Tom O’Connor for helping me with footnote 8 in chapter 6. Thanks to Micah Barnott for doing so much to advance reason, but asking for so little in return.

Thanks to Renee Barnett for being an inspiring friend and an everdependable source of support. Renee has an incredible career ahead of her. Thank you Guy P. Harrison, Brom Anderson, and John W. Loftus for friendship and patience in answering my questions. Thanks to Avram Hiller for his incredibly helpful contributions to all of my presentations.

Thank you to those at Portland State University who supported me, most notably the Philosophy Department chair, Tom Seppalainen. Tom, thank you again for providing me with an opportunity when nobody else would. You are the last believer in the meritocracy. Special thanks to my colleague who told me, “Even if you published ten critically received books from Harvard you’d never get tenure here.” Your words are a constant source of motivation.

Locally, thanks to Center for Inquiry (CFI)–Portland and Sylvia Benner; Humanists of Greater Portland and Del Allen; Oregonians for Science and Reason and Jeanine DeNoma; Josh Fost, Christof Teuscher, Erik Bodegom, and Amanda Thomas for your contributions to reason, rationality, critical thinking, and the public understanding of science. You’re making our community better.

Nationally, thanks to Mike Cornwell, Elisabeth Cornwell, Suzy Lewis, Joel Guttormson, Todd Stiefel, Kurt Volkan, D. J. Grothe, Greg Stikeleather, and Sean Faircloth. You didn’t know me, but you were very kind to me. Your efforts at making our society more rational and more thoughtful matter.

Thanks to Dan Barker, Annie Laurie Gaylor, and the Freedom From Religion Foundation for your practical, applied efforts in fighting irrationality in a way that I never could. In particular I’d like to thank Andrew Seidel for being on the frontline. Your efforts are making a difference.

Thanks to my past and present students for engaging and challenging me.

Thanks to everyone who read drafts and commented on

A Manual for Creating Atheists

: Sylvia Benner, Steven Brutus, Bruce Carter, John Diggins, Steve Eltinge, Alan Litchfield from “The Malcontent’s Gambit” (

http://www.malcontentsgambit.com/

), Gary W. Longsine, Justin Vacula, and Bob Williams.

Thank you to Massimo Pigliucci and Stephen Law for their original contributions to this book.

Thanks to my old, dear friend and editor, Christopher Johnson. Before I realized his e-mail signature is “Your best friend!” I was under the assumption—for years—that he thought that I thought that we were best friends.

Thanks to William Guy Hart for (unbeknownst to me) starting and maintaining my Facebook page. Thanks to Steven Humphrey from the

Portland Mercury

for taking a gamble on my articles. Samantha Russell, thank you for your lovely paintings and for your continued support.

Especially profound and heartfelt thanks to Steve Goldman and Matt Thornton for their invaluable help, council, advice, and authentic friendship. When I have questions about philosophy, Steve is my go-to. Steve and Matt were kind enough to let me record our conversations and copy our e-mail correspondence. Portions of those conversations are found throughout the book.

Thanks to Paul Pardi and philosophynews.com for hosting some of my content, driving down to Portland to review my “Easter Bunny” talk, being incredibly supportive of my work, and interviewing me for my first podcast.

Many people helped me with this project. Please accept my apologies if I failed to mention anyone, and thank you to all my supporters.

Finally, thanks in advance to those who’ve agreed to let me sleep on their couch when I go into hiding after the publication of this book.

APPENDIX A: CONSENSUS STATEMENT REGARDING CRITICAL THINKING AND THE IDEAL CRITICAL THINKER

We understand critical thinking [CT] to be purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which that judgment is based. CT is essential as a tool of inquiry. As such, CT is a liberating force in education and a powerful resource in one’s personal and civic life. While not synonymous with good thinking, CT is a pervasive and self-rectifying human phenomenon. The ideal critical thinker is habitually inquisitive, well-informed, trustful of reason, openminded, flexible, fair minded in evaluation, honest in facing personal biases, prudent in making judgments, willing to reconsider, clear about issues, orderly in complex matters, diligent in seeking relevant information, reasonable in the selection of criteria, focused in inquiry, and persistent in seeking results which are as precise as the subject and the circumstances of inquiry permit. Thus, educating good critical thinkers means working toward this ideal. It combines developing CT skills with nurturing those dispositions which consistently yield useful insights and which are the basis of a rational and democratic society (American Philosophical Association, 1990, p. 2).

APPENDIX B: “INTRODUCING SOCRATES” SYLLABUS

Instructor:

Peter Boghossian

Course Description:

In this 8-hour critical thinking class we will think through some difficult questions together, articulate our responses to those questions, and assess our reasoning.

Objectives:

1) Learn how to identify consequences

2) Learn how to reason through a problem (problem-solving)

3) Learn how to assess our thinking

4) Learn how to assess our current relationships

5) Learn how to articulate our ideas

6) Develop higher stages of moral reasoning

7) Develop verbal self-control

8) Understand how our identities are formed

9) Understand the roles that pleasure-seeking and gratification play in our lives

Class Structure

:

The class has two separate parts: (1) Discussion Questions, and (2) Discussion Analysis.

Part I

Discussion Questions

Every 25 minutes we will start with a question that is taken, in some form, from the Platonic dialogues (on occasion we may start with a reading from the dialogues). For example, a typical question could be, “How much control do we have over who we are?” We will then think through the question, and pose possible answers. I will participate in the discussion as a guide.

The discussion could take any one of a number of unexpected turns. It is okay if it does—evaluating different responses and analyzing those responses is part of the practice of learning. Until you become accustomed to the way that issues will be discussed, this may be perceived as a lack of structure. Also, if you are used to more formal class settings where exactly what you will learn is mapped out in detail beforehand, then this way of teaching class may initially be difficult for you. This is something that you need to be aware of in our discussions.

Part II

Discussion Analysis

The next 5 minutes we will analyze the discussion. We will identify the stages and process of our reasoning, assess our thinking, and attempt to figure out how we could have been more effective both in our reasoning and in our articulation. We will use what we have learned in the next discussion.

I have the following expectations:

- That you will be respectful of others. This does not mean that you have to agree with someone else’s viewpoint, but you do need to let them speak without

personally

criticizing them. - That you will ask if you have any questions, or if something is unclear. If something is bothering you, then you need to tell me.

- At times in our discussion I may say “STOP!” If I do, this means that we need to stop what we are doing, and I will direct you to write about what we are discussing.

What are the expectations that you have of me?

Finally

We can make this a very rewarding experience for everyone involved. It is an opportunity for us to explore issues and ideas in a way that challenges us intellectually. We will have an opportunity to think about ideas that everyone has wondered about, but few have had an opportunity to explore in depth in a classroom setting. My role is to help you articulate your thoughts and give you a process to evaluate critically your ideas. But there is only so much that I can do. Ultimately, you must take responsibility for your own learning. So perhaps our first question should be, “What does it mean to take responsibility for our learning?”

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

The following are questions that we will be asking ourselves throughout this course. I have listed the names of where these ideas can be found in the event that you would like to read more on your own. Unless otherwise stated, all names refer to works written by Plato.

- What is it to be a man? What is it to be virtuous? (

Apology, Meno

) - What is courage? (

Laches

) - Do people knowingly do bad things? (

Gorgias, Protagoras, Hippias Minor

) - What is justice? (

Republic

) - Are people responsible for who they become? (

Republic

) - Can a man be unjust toward himself? Can one be too modest? (Immanuel Kant’s “Metaphysics of Virtue,” in the first part of the

Metaphysics of Morals

,

Gorgias

, Aristotle’s

Nicomachean Ethics

) - Why obey the law? (

Crito, Republic

) - What’s worth dying for? (

Apology, Crito

) - When is punishment justified? (

Gorgias, Crito

) - How important is personal responsibility? What does “character counts” mean? (

Republic, Gorgias, Laws

) - Are customs and conventions important? What kinds of customs and conventions are there (styles, manners, laws, social class)? (

Republic

) - What’s the best life? What are the possible lives we can lead? Is the life of the tyrant the best life? (

Republic

) - How much control do we have over who we are? (

Republic

) - What obligations do we have toward others? (

Republic

) - What are the claims of loyalty and friendship? (

Republic, Lysis

) - What are our obligations toward our families? (

Republic

) - What makes a way of life appealing to us? What attaches people to the way of life? (

Republic

)

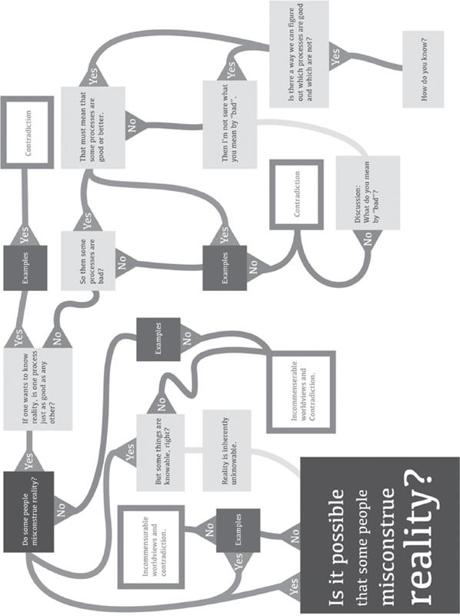

APPENDIX C: ANTIRELATIVISM ROADMAP

GLOSSARY

Agnostic

Someone who’s unsure whether or not God(s) exist.

Apologetics

A defense of the faith. (The word “apologetics” is often misunderstood as an apology for faith or for having faith.)

Aporia

Confusion, puzzlement, perplexity. The state of pause caused by philosophical examination.

Atheist

- A person who does not think there’s sufficient evidence to warrant belief in God(s), but who would believe if shown sufficient evidence.

- A person who doesn’t pretend to know things he doesn’t know with regard to the creator of the universe.

Auditing

A practice in the Church of Scientology in which a minister or a ministerin-training gives “auditing commands” to a person, referred to as a “preclear.” Auditing commands are questions or directions.

Augustine (St. Augustine of Hippo) (354–430)