A More Perfect Heaven (10 page)

Read A More Perfect Heaven Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

The difficulty of the work, coupled with the press of his other duties, may have held Copernicus’s anxieties at bay while he was writing his book about the heavenly revolutions. Since he kept no log of his progress, and no one witnessed his isolated toil, it is difficult to say which sections he wrote when, or how long he labored over each. The last observation mentioned in its pages is the one he made on March 12, 1529, when the Moon passed in front of the planet Venus and hid it from view.

“I saw Venus beginning to be occulted by the Moon’s dark side midway between both horns at one hour after sunset—the start of the eighth hour after noon,”

he reported. “This occultation lasted until the end of that hour or a little longer, when I observed the planet emerging westward on the other side. Therefore, at or about the middle of this hour, clearly there was a central conjunction of the Moon and Venus, a spectacle that I witnessed at Frauenburg.” He used that observation, paired with others from antiquity, to describe the revolutions and mean motions of Venus, in several pages’ worth of diagrams and geometrical proofs spelled out in his small, neat handwriting.

3

With his book virtually complete by 1535, Copernicus lost courage. He worried that his labored calculations and tables would not yield the perfect match with planetary positions that he had aimed to achieve. He feared the public reaction. He empathized with the ancient sage Pythagoras, who had communicated his most beautiful ideas only to kinsmen and friends, and only by word of mouth, never in writing.

Despite the decades of effort invested in the text, Copernicus eschewed publication. If his theory appeared in print, he said, he would be laughed off the stage. No argument from Giese could change his mind.

Other supporters also tried to sway him. In the summer of 1533, for example, the distinguished linguist and diplomat Johann Albrecht Widmanstetter, then secretary to Pope Clement VII, delivered a lecture on Copernicus’s astronomy in the Vatican gardens. Widmanstetter went on, after Clement’s death the following year, to serve Nicholas Schönberg, the Cardinal of Capua, and to awaken in him a profound desire to see Copernicus’s book published.

On November 1, 1536, the cardinal wrote from Rome:

“Some years ago word reached me concerning your proficiency, of which everybody constantly spoke.”

Cardinal Schönberg had traveled to Poland in 1518 on a peacekeeping mission. Although Albrecht and the Teutonic Order rebuffed his gestures, Bishop Fabian Luzjanski had entertained him in Varmia. “At that time I began to have a very high regard for you, and also to congratulate our contemporaries among whom you enjoyed such great prestige. For I had learned that you had not merely mastered the discoveries of the ancient astronomers uncommonly well, but had also formulated a new cosmology. In it you maintain that the Earth moves; that the Sun occupies the lowest, and thus the central, place in the universe; that the eighth heaven remains perpetually motionless and fixed; and that the Earth, together with the elements included in its sphere, and the Moon, situated between the heavens of Mars and Venus, revolves around the Sun in the period of a year. I have also learned that you have written an exposition of this whole system of astronomy, and have computed the planetary motions and set them down in tables, to the greatest admiration of all. Therefore with the utmost earnestness I entreat you, most learned Sir, unless I inconvenience you, to communicate this discovery of yours to scholars, together with the tables and what ever else you have that is relevant to this subject. Moreover, I have instructed Theodoric of Reden

4

to have everything copied in your quarters at my expense and dispatched to me. If you gratify my desire in this matter, you will see that you are dealing with a man who is zealous for your reputation and eager to do justice to so fine a talent. Farewell.”

Copernicus received this letter, read it perhaps several times over, and then, without responding, filed it away for future use.

From one sack of either grain, wheat or rye, cleansed of any grass or weeds before grinding in order that the bread may come out cleaner and purer … a careful weighing shows that at least 66 pounds of bread are produced, not counting the weight of the baskets.

—FROM COPERNICUS’S

Bread Tariff

, CA. 1531

Having banished the Lutherans from Varmia, Bishop Ferber set about putting his own house in order. How shameful, he complained in February of 1531, that in the entire chapter there was barely one priest entitled to celebrate Mass. A general lack of Holy Orders had long characterized the canons at Frauenburg, but now the bishop, who was himself ordained, implored them all to receive their orders—the special grace, imparted by the laying on of hands, that empowered them to administer the sacraments—before Easter. He peered into the private corners of the canons’ lives and did not hesitate to censure the slightest infraction. The fifty miles separating the bishop from his subordinates apparently posed no impediment to his learning of their lapses, as when he found out how Canon Copernicus’s former housekeeper, though long since discharged, had recently returned to Frauenburg and spent the night with him.

The bishop discreetly took pen in his own hand on this occasion, circumventing his personal secretary. As he recalled—or more likely was reminded by an informant—the housekeeper had married hurriedly after being let go, as though to cover an inconvenient pregnancy, but later separated from her husband. The bishop understood such things. He, too, had been in love as a youth, until his intended jilted him. He fought hard to defend his claim to her hand, producing articles of her clothing as proof of their intimacy, filing suit against her family in the papal court, and traveling to Rome to plead the case himself. When his beloved ultimately wed another man, Maurycy Ferber entered the priesthood.

Now Bishop Ferber called Copernicus to account for his assignation. With the Mother Church under Lutheran attack, no breach of decorum could be borne.

“My noble lord,”

Copernicus replied on July 27, 1531, “

Most Reverend Father in Christ, my gracious and most honorable lord

:

“With due expression of respect and deference, I have received your letter. Again you have deigned to write to me with your own hand, conveying an admonition at the outset. In this regard I most humbly ask your Most Reverend Lordship not to overlook the fact that the woman about whom you write to me was given in marriage through no plan or action of mine. But this is what happened. Considering that she had once been my faithful servant, with all my energy and zeal I endeavored to persuade them to remain with each other as respectable spouses. I would venture to call on God as my witness in this matter, and they would both admit it if they were interrogated. But she complained that her husband was impotent, a condition which he acknowledged in court as well as outside. Hence my efforts were in vain. For they argued the case before his Lordship the Dean, your Very Reverend Lordship’s nephew, of blessed memory, and then before the Venerable Lord Custodian [Tiedemann Giese]. Hence I cannot say whether their separation came about through him or her or both by mutual consent.

“However, with reference to the matter, I will admit to your Lordship that when she was recently passing through here from the Königsberg fair with the woman from Elbing who employs her, she remained in my house until the next day. But since I realize the bad opinion of me arising therefrom, I shall so order my affairs that nobody will have any proper pretext to suspect evil of me hereafter, especially on account of your Most Reverend Lordship’s admonition and exhortation. I want to obey you gladly in all matters, and I should obey you, out of a desire that my services may always be acceptable.”

Copernicus’s official services at this date made him a guardian of the chapter’s counting table. He and Giese, the other guardian, worked side by side collecting installment payments from wealthy individuals who had bought land or commercial operations from the diocese. They also managed the chapter’s endowment funds and invested its money in various capital ventures, including the construction of a tavern and inn in Frauenburg. The guardians made new purchases—of properties and sometimes supplies as well, such as “cannon, handguns, lead, and powder for the defense of the Cathedral”—and they paid the salary for the cathedral’s preacher.

Probably in the line of his duties as guardian in 1531, Copernicus created his undated

Bread Tariff

. This handwritten document aimed to fix the price of a peasant’s daily loaf at an affordable one penny—while simultaneously protecting the interests of the chapter-operated bakery. He advised adjusting the weight of a penny loaf according to the price of grain. Approaching the problem with his typical thoroughness, he calculated a sliding scale to cover a wide range of foreseeable market fluctuations. When harvests were plentiful and grain sold for a pittance, say nine shillings (fifty-four pence) a sack, the peasants would share the bounty, because their penny loaves would weigh in excess of one pound apiece. In lean years, however, should grain prices skyrocket as high as sixty-six shillings per sack, then Copernicus prescribed a loaf of bread had necessarily to shrink to one sixth of a pound. The chapter could recoup its other costs of production—baker’s wages, yeast—from the separate sale of bran and chaff.

While guardian, Copernicus made frequent trips to Heilsberg in his capacity as chapter physician, for Bishop Ferber was not a well man. Doctor Copernicus consulted several times with the king’s physicians about his treatment. The bishop, partially disabled by an illness years earlier, seemed unable to regain his strength. He perforce sent proxies to meetings where his presence was required. By 1532, age sixty-one, he faced his failing health by naming a coadjutor to aid and eventually succeed him. Not surprisingly, he chose Giese. But King Sigismund interceded and gave the post instead to a career diplomat named Johannes von Höfens, often called Johannes Flaxbinder because his ancestors worked as rope makers, and who signed his poems and letters Johannes Dantiscus, in homage to Danzig, his birthplace.

Dantiscus had spent years angling for a lucrative Varmia canonry. The king first nominated him in 1514, to be Andreas’s coadjutor, but the papal court endorsed someone else. The sudden decease of another canon in 1515 again enabled the king to name Dantiscus as a replacement, but this time both the chapter and the pope opposed him. Still the king continued to favor Dantiscus, not forgetting the long love poem he had written three years earlier—the epithalamion for the royal wedding of Sigismund and Barbara. (By 1515, the young queen already lay in her grave, only twenty years old when she died giving birth to her second daughter.)

Dantiscus made his next attempt at a canonry in 1528, while representing Poland at the Spanish court—shortly after he successfully negotiated for Sigismund’s new queen, Bona Sforza, the title she desired as Duchess of Bari. Dantiscus’s third bid actually won the chapter’s support, but failed again in Rome. Finally, on his fourth try, in 1529, Dantiscus got his wish. And then, the very next year, as though to reward his persistence, the king chose Canon Dantiscus to be Bishop of Kulm. The nearby diocese of Kulm was home to the Cistercian convent where Copernicus’s sister Barbara had become a nun. Although Kulm could not compare with Varmia in political power or wealth, Dantiscus gladly anticipated putting on the miter. He remained in Spain the next two years, however, to complete his government mission there and also to see to the business of receiving Holy Orders, in order to become a priest prior to ascending to the bishopric.

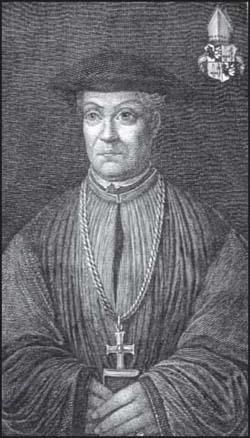

Johannes Dantiscus, Bishop of Varmia.

Returning to Poland in 1532 as Bishop-designate of Kulm, he made a strong candidate for coadjutor to the ailing Bishop Ferber. While he awaited the outcome of that contest, he invited two of his fellow Varmia canons—Copernicus and Felix Reich, but not Giese—to attend his long-overdue investiture ceremony in Löbau on Sunday, April 20, 1533. Both the invited canons begged off.

“Your Lordship, Most Reverend Father in Christ,” Copernicus wrote, “I have received your Most Reverend Lordship’s letter, from which I quite understand your kindliness, graciousness, and good will toward me. … This is surely attributable, not to my services but rather, in my opinion, to your Most Reverend Lordship’s well known generosity. Would that I might some day chance to be so deserving! I am of course more delighted than it is in my power to say that I have found such a patron and protector.

Other books

Winsor, Kathleen by Forever Amber

Unpredictable Love by Jean C. Joachim

The Darkest Minds by Alexandra Bracken

3 - Cruel Music by Beverle Graves Myers

Dark Harbor by Stuart Woods

Fireflies by Ben Byrne

Circle of Three by Patricia Gaffney

5 Onslaught by Jeremy Robinson

Call Of The Flame (Book 1) by James R. Sanford

Summer Shorts-Four Short Stories by Jan Miller