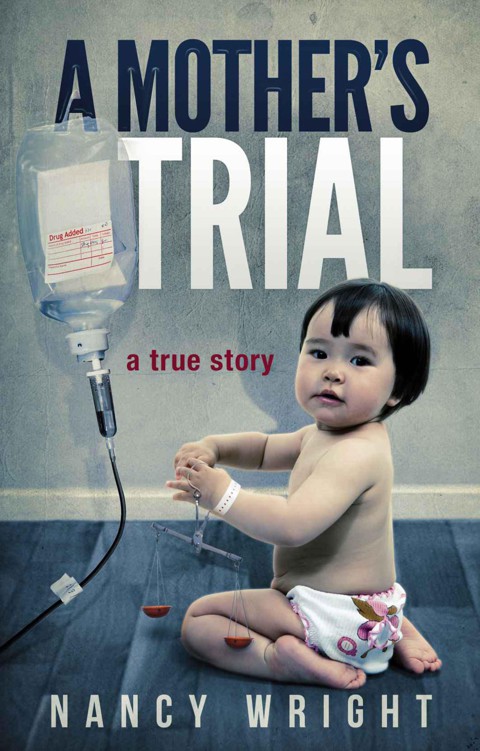

A Mother's Trial

A MOTHER'S TRIAL

by

NANCY WRIGHT

Produced by

ReAnimus Press

© 2012, 1984 by Nancy Wright. All rights reserved.

Licence Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

~~~

For Al, Emily and Philip

~~~

Table of Contents

You can come to the conclusion that every life event is purely a personal perception. Maybe the essence of it all is that truth is evasive. Maybe there is no such thing as truth: Truth is what you want it to be. And what a large number of people agree upon as truth is truth.

Dr. Michael Applebaum March 21, 1982

Acknowledgments

Over one hundred people contributed time and effort to this book. Among them were some who are special.

To Ted Lindquist of the San Rafael Police Department; for sacrificing hours of scant free time to help me, asking in return only that I tell the truth (I hope he is not disappointed); to Evelyn Callas; for poring over Tia’s and Mindy’s records with me, offering always patient explanations to a pupil whose natural skills and acumen were certainly less than what she was accustomed to; and for resisting pressure from significant forces which preferred she keep silent; to all the others I interviewed; for freely volunteering enormous amounts of aid and information; to Dr. Larry Schwartz; for reading the manuscript and making valuable suggestions; to family and friends; for their editorial assistance; and for bearing with an obsessed personality both patiently and uncritically for over four years; and most especially to my brother, Tony Ganz; for supporting me and this project from the beginning; for reading the manuscript at various stages with sensitivity and perception; and for encouraging me to keep going on the occasions when it would have been easier to quit:

Thank you.

Author’s Note

This is a true story. The events and people—and the scenes involving them—are real.

To protect their privacy, the names of some individuals have been changed.

This ebook edition is an exact copy of the edition first published by Bantam Books in December, 1984, and reprinted four times. Any errors of transcription are the result of the faulty scan and aging eyes of its proofreader. The ebook does correct, however, one 28-year-old injustice. Ted Lindquist attended Arizona State University, not its bitter rival, the University of Arizona.

Prologue

On Wednesday morning, February 22, 1978, Priscilla Phillips angled her car into a marked stall in the parking lot in back of the hillside site occupied by San Rafael’s Kaiser Hospital. At eight in the morning, cars were scarce. The clinics would not open for another half an hour, and those doctors arriving early commonly parked by the Emergency entrance. But Priscilla could not wait until eight-thirty. Concerned about Mindy, she had not slept well, tossing with half-framed dreams of anxiety and unfulfilled obligations.

Priscilla, a heavyset woman, with bones too small for the weight she had added in recent years, closed the car door with a thump that sounded hollow in the fog of the February morning.

As the main clinic doors were still locked, Priscilla walked around to the Emergency entrance and started for Five West, the pediatric ward, where her first adopted daughter, Tia, had spent much of her short life.

Priscilla Phillips emerged from the elevator on the fifth floor and turning right, entered the pediatric ward, and walked across to the deserted nurses’ station. There was a distant sound of a baby crying. For a moment Priscilla tried to recall who was on duty. She knew all the regular nurses in pediatrics. That had been a godsend when Mindy became sick. Everyone said it was a mistake to adopt a second Korean child so soon after losing Tia. But both she and Steve had insisted, even in the face of the adoption agency’s initial resistance to the idea. Just nine months after Tia’s death, Mindy was delivered to them. That had been four months ago. Within a few weeks, she, too, fell sick.

Mindy’s illness—just like Tia's—was initially diagnosed as gastroenteritis. She improved and after nine days was discharged. But after only three days at home she was admitted again, at 2:45 A.M. on February sixteenth, with severe diarrhea and vomiting.

In the six days since, her condition had fluctuated, but the diarrhea continued and intravenous therapy was initiated. As Priscilla knew from her experiences with Tia, without an IV a severely dehydrated child could die within fifteen minutes.

The sound of her heels loud in the vacant corridor, Priscilla crossed back to the small utility room where the nurses kept Mindy’s Cho-free formula in a refrigerator. There she poured some of the Cho-free from the liter bottle into a baby bottle, stoppered it with a clean nipple, and started for room 503, directly across from the nurses’ station. They had put Mindy in the same room Tia had occupied for so many weeks.

Mindy was awake. At thirteen months she was small for her age, although not as small as Tia had been. She wrinkled up her broad nose and squinted up smiling at her mother. Beside her, the IV line rattled slightly as she moved.

Priscilla looked down at her, the light from the window touching and then glancing off Mindy’s short black hair. Then she took a seat by Mindy’s bed and reached for her daughter to offer her the formula.

It was a gesture she had made repeatedly in her thirty-two years. It was a mother’s gesture. But in the months to come, there would be many people calling it something other—something, in fact, terribly different.

THE FORMULA

1

The modern, cement complex of Kaiser Hospital in San Rafael, Marin County, was one of thirteen Kaiser hospitals in the northern California region. It sat—pink and squat—in the low, rounded hills of the section of San Rafael called Terra Linda. Only two years old, it consisted of three interlocking buildings: the General Services Building, the Medical Office Building, and the hospital itself. With a patient membership of about 80,000 and a bed capacity of 92, this facility was among the smaller medical centers in the region. Its staff of 74 doctors included 9 pediatricians.

It was a pleasant place to work, particularly for those on the staff who had known the old dim and crowded San Rafael offices. The center was well-designed and maintained. The pediatricians’ offices, on the third floor of the Medical Office Building, were small but adequately furnished, each with natural light supplied by a decent-size window. Initials A through D had been parceled out to the four clusters in the pediatric section. Dr. Sara Shimoda, along with Drs. Evelyn Callas and Richard Viehweg, were assigned to Pediatrics B.

While Priscilla Phillips fed her daughter, thirty-six-year-old Sara Shimoda sat alone in her office. A beautiful woman with porcelain skin and dark, expressive eyes set in an oval face, she wore about her a cloak of stillness and reserve that had always prompted others to reach out to her. As a doctor she carried an extra burden of cultural history that insisted that women remain in the background, and this tended to make her hesitant and occasionally distrustful of her sure instincts and first-class intelligence.

Today Sara was to present the case of Mindy Phillips at the weekly department meeting due to start at eight forty-five. She did not look forward to it. She hated speaking in meetings, even among friends. But this was not the primary reason for her apprehension. This morning, her fears were professional rather than personal because she was to present the case of Mindy Phillips. And except for its uncanny resemblance to that of Tia Phillips, everything about this child’s case was unusual.

For one thing, Sara knew she had a particularly close relationship with Mindy’s mother. It had always been hard to explain what attraction Priscilla Phillips held for Sara, but she was aware that it was more than their superficial resemblances in age or life-style. They had met at the American Association of University Women (AAUW)—Priscilla had been vice-president in charge of membership at the time Sara joined—but they did not approach that group, or anything else, in the same way. Sara knew well her tendency to sit quietly on the edges of things. In the months after their first meeting, she saw Priscilla volunteering her time, holding office, always at the forefront with ideas for activities or special projects. While Sara guarded her feelings, Priscilla hugged, kissed, cried, laughed, and even argued—all in public. It had to be their differences that attracted each to the other.

Certainly their early backgrounds differed dramatically. Sara had been born in the farm belt of central California and had grown to adolescence there. An undergraduate career at the University of California in Berkeley, and medical school at UCSF followed.

In 1971, by then comfortably married to a teacher of the handicapped named Tom Post, Sara joined the staff at Kaiser. In the seven years that followed, she dealt with many parents, but none affected her in quite the same way as did the Phillips family.

Priscilla had left an indelible impression on Sara at that introductory meeting of the AAUW. As she passed around her first pictures of the little Korean orphan she planned to adopt, she was so openly excited that Sara felt herself pulled into the event, too.

Later, of course, Tia had drawn Sara in. Tia, who resembled Sara’s own daughter in both age and appearance, was a beautiful and loving child.

When Tia was under her care, Sara had broken down more than a few times. The period after the laparotomy had been the worst, when she could offer no more hope, when comforting words rang false: she had known Tia was probably going to die.

By then friends and colleagues on the staff were warning Sara about her involvement with the family, insisting that Priscilla Phillips was like a leech, and that Sara must guard herself lest she be sucked dry. She found this perception of Priscilla puzzling: it was not how she saw her. Certainly Priscilla was demanding and intense, but Sara could do nothing but admire the woman for her devotion to Tia. At times she had to force Priscilla to go home. Priscilla always tried so hard, helping uncomplainingly with everything. She had always been right there when Tia needed her—as she was now for Mindy.

Sara had been increasingly troubled about Mindy. Her symptoms made no medical sense at all. As Sara crossed the hall to the Pediatric Conference Room the staff used for their weekly meeting, Mindy’s plastic-covered chart in her hand, she wondered how her colleagues would react to her admission of failure.

Sara’s case presentation, the first item on the agenda, was brief. In the small, plain room, she did not have to raise her soft voice. She began with the patient’s history.