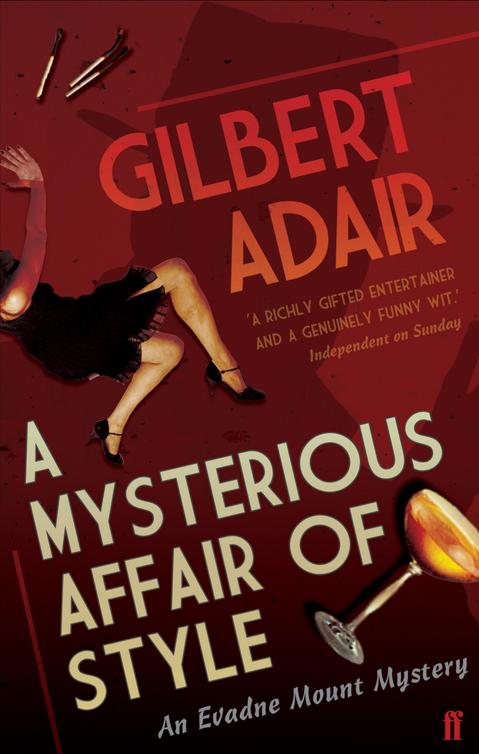

A Mysterious Affair of Style

Read A Mysterious Affair of Style Online

Authors: Gilbert Adair

GILBERT ADAIR

The cinema is not a slice of life but a slice of cake.

ALFRED HITCHCOCK

- Title Page

- Epigraph

-

- To My Editor, Walter Donohue

-

- Part One

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

-

- Part Two

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- Chapter Eleven

- Chapter Twelve

- Chapter Thirteen

- Chapter Fourteen

- Chapter Fifteen

- Chapter Sixteen

-

- About the Author

- Copyright

Dear Walter,

When, prompted by your enthusiasm for

The Act of Roger Murgatroyd

, you proposed that I write a sequel, I immediately rejected the idea on the grounds that I’ve always made it a point of honour never to repeat myself. Later, however, it occurred to me that I had never written a sequel before (to one of my own books, at least) and hence, applying what I acknowledge is a slightly warped species of logic, to write one now would represent another new departure for me. So if, to adapt Hitchcock’s metaphor, fiction can also be a slice of cake, I hope you’ve left room for seconds.

Gilbert

‘Great Scott Moncrieff!!!’

That voice!

Chief-Inspector Trubshawe – or, if one is to be a stickler for accuracy, Chief-Inspector Trubshawe, retired, formerly of Scotland Yard – had just stepped into the tea-room of the Ritz Hotel in quest of repose for his feet and refreshment for his palate, and it was while endeavouring to attract the eye of a waitress that he heard the voice which caused him to stop dead in his tracks.

If the truth be told, the Ritz was not the kind of establishment to which he would normally have accorded his patronage, certainly not for the steaming cup of tea which, for the past hour, he had craved. He had never been one to throw his money about, the less so since having had to learn to subsist on a police officer’s pension, and a Lyons Corner House would have been more to his unashamedly plebeian tastes. But he had found himself by chance at the posher end of Piccadilly, whose sole common-or-garden tea-room had

teemed with secretaries and short-hand typists gabbling away to one another about the trials and tribulations of their respective working days, all of which had simultaneously come to a close. It was, then, the Ritz or nothing; and he thought to himself, alert to the incongruous reversal of values, well, why not, any old port in a storm.

So there he was, in this unostentatiously elegant room – a room in which the dulcet drone of upper-crust conversation clashed harmoniously (if such an oxymoron is possible) with the silvery rustle of the finest cutlery, a room he had never entered and had never expected to enter in his life – and before he had even properly orientated himself, he had run into somebody from his past!

The person who had hailed him was seated by herself at one of the tables located near the door, her face just visible behind a wobbly stack of green-jacketed Penguin paperback books. When he turned his head to confront her, the voice boomed out a second time:

‘As I live and breathe! Do these rheumy eyes of mine deceive me or is it my old partner-in-detection, Inspector Plodder?’

Trubshawe now looked directly at her.

‘Well, well, well!’ he exclaimed in surprise. Then, a note of sarcasm creeping almost imperceptibly into his voice, he nodded, ‘Oh yes, it’s Plodder all right. Plodder, alias Trubshawe.’

‘So it

is

you!’ said Evadne Mount, the well-known mystery

novelist, ignoring the faint but meaningful modification of his tone. ‘And you do remember me after all these years?’

‘Why, naturally I do. It’s an essential part of my job – I mean to say, it used to be an essential part of my job – never to forget a face,’ laughed Trubshawe.

‘Oh!’ said the slightly deflated novelist.

‘Except,’ he added tactfully, ‘when you and I first met, it was

after

I’d retired, was it not, which must mean that in this instance it’s a personal not a professional memory. Actually,’ he concluded, ‘it was the voice that did the trick.’

Here came that note of sarcasm again. ‘And the disobliging nickname, of course.’

‘Oh, you must forgive my jollification. “She only does it because she knows it teases”, what? Good heavens, it really is you!’

‘It

has

been a while, hasn’t it?’ said Trubshawe dazedly, shaking her hand. ‘A very long while indeed.’

‘Well, sit down, man, sit down. Take the weight off your brains, ha ha ha! We must talk over old times. New times, too, if you’re so minded. Unless,’ she said, dropping her voice to a self-consciously theatrical stage-whisper, ‘unless you happen to be here on a romantic assignation. If that’s the case, you know me, I wouldn’t want ever to be

de trop.’

Trubshawe lowered himself onto the chair opposite Evadne Mount’s, his broad boxer’s shoulders heaving as he dusted down his trouser-knees.

‘Never had such a thing as a romantic assignation in my

life,’ he said with no apparent regret. ‘I met my late missus – Annie was her name – when we were both in the same class at school. I married her when we were in our twenties and I was just a callow young constable on the beat. We had our wedding reception – a real slap-up do it was, too – in the dance-hall of the Railway Hotel at Beaconsfield. And until she passed away, ten years ago now, I never once looked back. Or sideways either, if you know what I mean.’

Evadne Mount sat back in her own chair and fondly took the Chief-Inspector’s measure.

‘What a charming, what a cosy, what an enviably conventional life you make it seem,’ she sighed, and she probably didn’t mean for her approval of that life to sound as condescending as it may well have done.

‘And, quite right, I remember now. Last time we met – the ffolkes Manor murder case

*

– you’d just become a widower. And you say that was all of ten years ago? Hard to believe.’

‘And what ten years they were, eh, what with the War and the Blitz and V.E. Day and V.J. Day and now this so-called bright new post-war world. I don’t know about you, Miss Mount, but I find that London has changed out of all recognition, and it’s not the better for it. Nothing but spivs, as far as I can see, spivs, Flash Harrys, black marketeers, motor bandits and these gangs of nylon smugglers I keep reading about.

‘And beggars! Beggars right here in Piccadilly! I’ve just spent the last half-hour strolling around Green Park, but I couldn’t bear it any more. I was endlessly pestered by a bunch of grimy street urchins begging for pennies then calling me a tinpot Himmler – pardon me, a tinpot ’immler – when I refused to give them any. Main reason I came in here was for some peace and quiet.’

‘Mmm,’ agreed the novelist, ‘I have to say this isn’t the kind of place I’d associate you with.’

‘It isn’t at that. I was on the lookout for some plain, ordinary, come-as-you-are cafeteria. You, on the other hand, strike me as quite at home here.’

‘Oh, I am. I drop in every day at this time for afternoon tea.’

These mutual pleasantries were interrupted by the arrival of a white-haired, white-capped waitress who hovered expectantly over Trubshawe.

‘Just a pot of tea, miss. And tell them to make it strong.’

‘Right you are, sir. Would you be wanting bread-and-butter with that, sir? Cucumber sandwiches, p’raps?’

‘No thank you very much. Just the tea.’

‘Right away, sir.’

Glancing at the neighbouring tables, most of which had been commandeered by plump, well-nourished dowagers, fur stoles drowsily curling about their necks like equally plump, well-nourished pet foxes, Trubshawe turned again to Evadne Mount.

‘There’s a lot of talk about austerity these days. Not much sign of it here.’

She smiled benignantly at him.

‘I do know what you mean,’ she answered in a voice whose habitual tenor was so stentorian that, even if she said not much more than ‘Pass the sugar, please’, it made heads turn as far as three or four tables away. ‘The War has complicated everything. It isn’t only London that’s changed. The whole country’s changed, the whole world, I dare say. No more manners, no more respect, no more deference. Not the way it was in our day.

‘But then, you know, Trubshawe, those grimy urchins you mentioned, those peaky-faced little ragamuffins? Don’t forget that, a mere couple of years ago, they were being bombed out of house and home by the Luftwaffe. When they insult you by calling you a tinpot ‘immler, well, that’s not just a name to them. It’s quite possible the Nazis were responsible for the deaths of their mothers or fathers or a half-dozen of their school chums. In these terribly trying times, I do believe we all need to be more indulgent than usual.’

Trubshawe took her point.

‘You’re right, of course. I’m just a crochety, antisocial codger, a crusty old curmudgeon.’

‘Pish posh!’ said Evadne Mount. ‘It’s been ten years since I last clapped eyes on you and you haven’t aged a bit. Really, it’s most remarkable.’

‘Now that I take a closer look,’ said Trubshawe in reply, ‘you neither. Why, I wager, if I were to run into you again in ten years’ time, you still wouldn’t have aged. It’s almost as though time has stood still – at least for you. For me too, if you say so. And, of course, for Alexis Baddeley. She never appears to age either.’

‘Alexis Baddeley, eh? My alter ego – or ought I to say, my alter egoist? Why, Trubshawe, don’t tell me you’ve become one of my readers? One of what I like to call the happy many?’

‘Yes, I have. As a matter of fact, ever since we, eh, we collaborated on that nasty Roger Murgatroyd affair, I’ve read every one of your whodunits. Just the other week I finished the latest. What was its title again?

Death: A User’s Manual

. Yes, indeed, I finished it last – last Wednesday it was.’

There followed a not-so-brief silence during which Evadne Mount patently began to feel it a mild discourtesy on the Chief-Inspector’s part to have mentioned the title of her most recent book, to have acknowledged having read it, then to have left it at that. Though she tended to be brazen in her relationship with publishers and readers, admirers and critics, it nevertheless was not her style ever to be the first to open up what might be termed the negotiations of praise – she would claim she never had to – but she found Trubshawe’s noncommittal response so frustrating that she finally queried:

‘Is that all?’

‘All what?’

‘All you have to say about my new book? That you finished it last Wednesday?’

‘Well, I …’

‘You don’t suppose you owe it to me to say what you thought of it?’

Just at that moment Trubshawe was served not merely the tea he had requested but a glazed cherry-topped bun he hadn’t. But before he’d had the chance to correct the waitress’s error, Evadne Mount raised her glass – only now did he notice that what she was drinking was a double pink gin, a drink that, by rights, should not have been available in a tea-room – and proposed a toast.

‘To crime.’

Unaccustomed though he was to toasting precisely those nefarious activities he had devoted his professional life to combating, Trubshawe nevertheless decided that it would be both pompous and humourless of him to refuse.

‘To crime,’ he said, raising his teacup.

He took a deep draught of the tea and, the waitress having already disappeared, an unexpectedly voracious bite out of the bun.

‘Actually,’ he continued, ‘I have to confess that – now this is just one man’s point of view, you understand – but I have to confess that I didn’t feel your new whodunit would ever become one of my own personal favourites.’

‘No?’ the lynx-eyed novelist, eyeing him like a hawk, rejoindered. ‘May I ask why not?’

‘Oh well, it’s all very clever and that, the tension building up nicely as usual, so that, as I read on, I was more and more gripped, just as I’m sure you intended me to be.’

‘Interesting you should say that,’ she immediately cut in. ‘It’s my theory, you see, that the tension, the real tension, the real suspense, of a whodunit – more specifically, of the last few pages of a whodunit – has much less to do with, let’s say, the revelation of the murderer’s identity, or the disentangling of his motive, or anything the novelist herself has contrived, than with the growing apprehension in the reader’s own mind that, after all the time and energy he has invested in the book, the ending might turn out to be, yet again, an anticlimactic letdown. In other words, what generates the tension you describe is the reader’s fear not that the

detective

will fail – he knows that’s never going to happen – but that the

author

will fail.’

‘But that’s just it,’ Trubshawe maintained, seizing the opportunity to cut back in. He had been inordinately indulgent with her, considering that she had after all solicited his opinion but, familiar as he was with her old ways, he was well aware that, if he permitted her to digress as freely as she was used to doing, he would never get around to letting her know what he actually thought of her book.

‘The suspense, as I say, was building up nicely to the scene in which your lady detective, Alexis Baddeley, re-examines

the suspects’ alibis. Then there comes that whole bizarre business of the drunken toff who keeps popping up all over the shop and … and, well, you lost me, frankly. Sorry, but you did ask.’

‘And yet it’s really quite simple,’ persisted Evadne Mount.

‘Is it? I must say I –’

‘You do know what a running gag is, don’t you?’

‘A running gag? Ye-es,’ replied the Chief-Inspector, not altogether sure that he did.

‘Of course you do. You must have seen one of those Hollywood comedies – screwball comedies I think they call them – in which the running gag is that some top-hatted toper keeps, as you say, popping up in the unlikeliest places and asking the hero in a slurred voice, “Haven’t I sheen you shomewhere before?” Am I right?’

‘Uh huh,’ he said as prudently as before.

‘So when the reader encounters the same type of character in

Death: A User’s Manual

, he thinks, aha, this must be the comic relief, just as it is in the films. But no, Trubshawe, in my book the toper really has seen the hero somewhere before. Where? Leaving the scene of the crime, of course. Because he’s pie-eyed, though, nobody pays the slightest bit of attention to him. Except for Alexis Baddeley, who insists that, inebriated or not, he’s a witness like any other and hence has to be taken as seriously as any other.

‘I like to think of it as my variation on “The Invisible Man”. The Father Brown story, you know.’

After listening to her argument no less patiently than she had presented it to him, Trubshawe shook his heavy head.

‘No, no, I’m sorry, Miss Mount, it won’t do.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Oh, I grant you, now that you’ve spelt it out for me, I just about get the hang of the idea. But it’s not good enough.’

Evadne Mount prepared to bristle.

‘Not good enough?’

‘I’ve read enough whodunits now – mostly yours, I have to say, though once I’d exhausted all of those, I found I was so addicted I even dipped into one or two thrillers of the thick-ear school, James Hadley Chase, Peter Cheyney –’

‘The adventures of Lemmy Caution, you mean? Ugh, not my thing at all.’