A Northern Thunder

Read A Northern Thunder Online

Authors: Andy Harp

Copyright 2007 by Col. J. Anderson Harp, Retired, USMC Reserves

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by electronic means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote passages in a review.

All the characters in this book are fictitious, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Published by Bancroft Press (“Books that enlighten”)

P.O. Box 65360, Baltimore, MD 21209

800-637-7377

410-764-1967 (fax)

www.bancroftpress.com

Cover and interior design: Tammy Sneath Grimes, Crescent Communications

www.tsgcrescent.com

• 814.941.7447

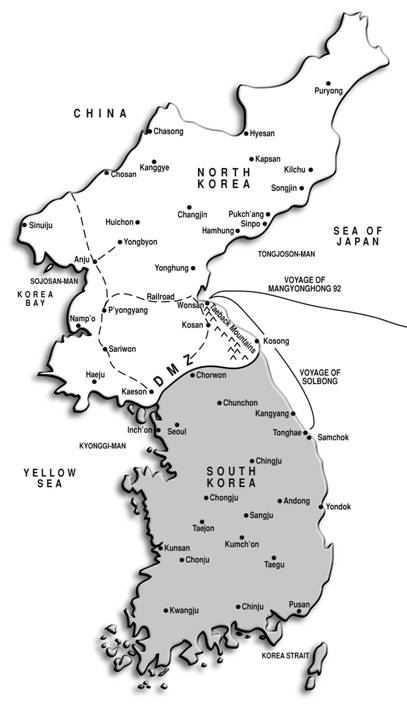

Map of Korea: Thom Hendrick

Author photo: Bob Hancock

ISBN 1-890862-53-3 (EAN: 978-1-890862-53-4)

LCCN 2006935333

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

To Jane and the gang, with love.

And to Ethel and Lucille, who have

encouraged the creative mind.

![]()

“I

s this seat 38?”

Dr. Myles Harbinger looked up to see a young Asian man. “Yes, I guess it is,” Harbinger said, glancing at the window seat beside him.

“Thank you,” said the young man. “If you’d rather have the window, I don’t mind.”

Though he cared little about the seat, Harbinger did not want to move. He simply wanted to not be disturbed. “No, young man, I’ll stay here. Thank you.”

Wrinkled and disheveled, with reading glasses on his gray, bushy head and an unlit pipe in his mouth, Harbinger looked every inch the professor he was. He had hoped the flight from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco would provide him an opportunity to work on his high-priority research project. He had treasured the promise of five hours of quiet time in the air, and hoped his seat neighbor would end the small talk quickly.

Fortunately, the young man said nothing else. He took off his leather jacket, sat down, and began reading a newspaper.

Out of the corner of his eye, Harbinger noticed the paper’s Korean script.

“Excuse me, sir,” said a flight attendant, “but you’ll need to store the table for take-off. May I take that briefcase for you?”

“Yes, thank you.” Harbinger handed the satchel across to her and, as she put it in the overhead bin, she noticed the attached tag:

Dr. Myles Harbinger, Ph.D.

121 Briar Street

Berkeley, California 94704

To the young Asian man, she said, “And may I take your coat?”

The young man hesitated briefly, and then handed his jacket to her. Later, as she hung it up in the forward cabin, she would notice it had no tags—of any kind—inside.

“And, Professor, you do know you cannot light that pipe?”

“Yes, my dear,” he replied. “And a good deduction. What gave it away?”

“Just a wild guess,

Professor

.” Harbinger enjoyed the emphasis she added to his title.

The man next to the professor also knew Dr. Myler Harbinger’s occupation, but not by any guess. He knew where Harbinger taught, how he dressed, what he liked and disliked. In fact, for several months, the man had researched every possible detail about the professor sitting next to him, including the precise airplane seat assigned him on this flight. A Ph.D. in mathematics and the world’s leading mind in the development of GPS—the Global Positioning Satellite network—Dr. Harbinger was the Grace Hopper of his time. Like Hopper, the famed naval captain, genius, and inventor of the COBOL computer system, Myler Harbinger was a decade ahead of his peers, except perhaps one.

“Where do you teach, Professor?” the young man asked in clear English.

“I’m at the Engineering Department at Berkeley.”

“Oh, a very fine school. And, engineering—I thought the computer eliminated our need for mathematics and engineering.”

Harbinger grumbled to himself. “No, we’ll always need engineering, and we’ll always need professors,” Harbinger replied. Silence followed, but only for a brief time.

“I work in cable television in South Korea,” the man eventually continued. “Without the satellite, we couldn’t exist. I’m sure the computer helped make that possible.”

The comment struck strangely close to Harbinger’s work. Suddenly, Harbinger felt uncomfortable.

“What brought you to Washington, Doctor? Or do you prefer Professor?”

“A meeting on satellites at NASA.”

“Oh, really?” the stranger said as he leaned over, peering at the computer screen.

Harbinger, feeling the man’s body enter his space, leaned back in his chair. “Excuse me,” he said.

“Oh, Doctor,” said the man, “I did not mean to cause you alarm. I was just curious. I find satellites most interesting. I cannot imagine a world without them. And the military—I would think it could be paralyzed if a satellite fails.”

Harbinger did not volunteer that this meeting at NASA had been, curiously enough, on that very subject. He did not mention the representatives attending from U.S. Space Command, nor their concern that space debris, whether natural or intended, could destroy a satellite—nor the effect that would have on the military and its aging, costly fleet of satellites.

For a long time, conversation ended, and Harbinger became so engrossed in his work that the stranger turned away, placed a pillow under his head, and fell asleep.

Several hours later, the flight attendant interrupted Harbinger. The other passenger was just emerging from a sound asleep. The attendant noticed his hands, particularly a scar covering the top of his left hand. It was a clean, deep scar with a sharp, clear edge—probably a knife wound, as if he’d protected himself from a blow.

She also noticed the ring on his other hand—unostentatious gold, and twisted in the shape of a dragon. To her, it looked out of place on his hand. He was not ornately dressed. Rather, he wore non-descript black clothing—a shirt, tie, and leather jacket—as if he hoped not to stand out. And, yet, he stood out by the way he dressed—at least to her. He seemed out of place while making an effort to appear

in

place.

“Gentlemen,” she said, “we have about an hour until we reach San Francisco. I apologize for the late meal. Would you care to have the chicken or the steak for dinner?”

“Miss,” Harbinger replied, “I believe I have a special meal ordered. Would you mind checking on that?”

“I would be happy to, Professor.” She turned to the man in black. “And you, sir? What would you like?”

“Miss, the steak would be fine.”

• • •

As the flight attendant cleared away their two meals, the young stranger tried to strike up another conversation.

“Professor,” he said, “did you know the United States wastes more food in a week than the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea consumes in a year?”

Harbinger had taught long enough at Berkeley to know how to interpret a comment like that. To the rest of the world, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, or DPRK for short, was known simply as North Korea. South Korean businessmen did not refer to North Korea as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Only a friend of North Korea would refer to it that way.

“I’ve heard that North Korea

has had

a difficult time,” Harbinger said.

“Yes, Professor. Its children are starving. Thirty-eight miles from Seoul, children are dying from malnutrition. They lie there, gasping for breath, a short drive from one of the largest, best-fed cities in the Pacific Rim.”

As Harbinger looked for a way to shift or stop the conversation, the pilot announced that the plane had been cleared for approach into San Francisco International Airport. Harbinger was thankful for the interrup-tion. This young man was more than a cable television businessman from South Korea, and the more Harbinger heard, the more he wanted the flight to end.

So Harbinger used the pilot’s landing announcement as an opportunity to begin closing down his portable office. He appeared pleasant as he turned off his computer and sorted his papers.

Shortly thereafter, the plane’s tires yelped as the weight of the Jumbo 767 settled down on the San Francisco runway. As the aircraft taxied to the gate, Harbinger’s thoughts turned to the class he had to teach tomorrow.

The rush of people to the front of the aircraft caused a bottleneck in first class, and Harbinger did not notice his row-mate twisting the gold ring on his finger as he got up from his seat. The man had no briefcase, bag, or satchel to remove from the overhead bin.

“Well, young man, I hope your remaining journey is pleasant,” Harbinger said, trying to show some civility.

“You too, Doctor.” The man sounded more serious as he placed his hand lightly on the Professor’s shoulder. Harbinger felt a small prick as the crowd surged toward the door, and as he turned to look, the man had already disappeared into the general shoving for the exit. Harbinger stepped forward, but as he did, pain struck his chest, as if a sledgehammer had knocked the breath out of his body, and he crumpled to the ground, his bags plopping down beside him. Passengers pushed from behind, not realizing Myles Harbinger, a world leader in micro-electronic technology, had a highly concentrated dose of sodium nitroprusside surging through his veins, and was dead even before his body slumped to the aircraft floor.

![]()