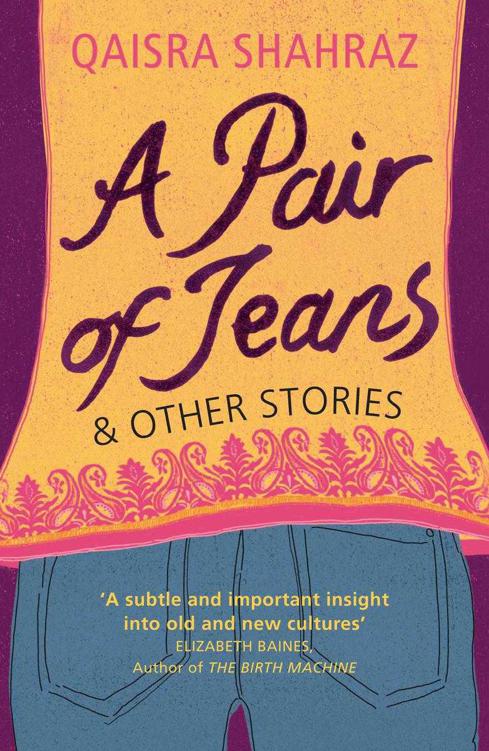

A Pair of Jeans and other stories

Read A Pair of Jeans and other stories Online

Authors: Qaisra Shahraz

Praise

‘Qaisra Shahraz movingly depicts the tensions for those caught between cultures old and new. Characters struggle with the concept of homeland, relationships between generations, and changing roles for women, and often triumph. A subtle and important insight.’

Elizabeth Baines, Author of

The Birth Machine

(Salt)

‘Qaisra Shahraz is in a position to bring to readers issues that most of us in the West are scarcely aware of at such a human level. She has the ability to bring East and West together through her writing.’

Jane Camens, Executive Director, Asia Pacific Writers & Translators, Australia

and other stories

Qaisra Shahraz

Dedication

This collection is for my lovely nieces, Sumer, Sophia, Sara, Zarri Bano, Sana, Safa, Maryam and Alissa.

I want to thank the following people for their work and support. John Shaw for the original word processing, Jen Thomas for marketing ideas and Margaret Morris for editing these short stories. My sister in law Dr. Afshan Khawaja for her general interest and support in my literary work. My German friend Prof. Liesel Hermes for liking and publishing my story

A Pair of Jeans

over 25 years and for the preface to this collection. Prof. Mohammed Quayum for his interest and publication of

Escape

and

Zemindar’s Wife

in Singapore and Malayasia. Ahmede Ahmed for the publication of

The Malay Host

in Bengladesh. Muneeza Shamsie for including

A Pair of Jeans

in her successful collection of stories,

And the World Changed

in India, Pakistan and the USA. Prem Kumar, Sami Rafiq and Tingting Xiong for their respective translation and publication of

A Pair of Jeans

into the Malayalam, Urdu and Mandarin languages. Similarly I want to thank Prof. Mohammed Ezroura in Morocco and Prof. Shuby Abidi in India for their academic papers on

A Pair of Jeans

. I want to thank Commonword Publishers/ Crocus Books in Manchester who first published some of these stories, including the

The City Dwellers, Discovery

and

The Elopement

. Finally my publisher Rosemarie Hudson, publisher of my novels

The Holy Woman

and

Typhoon

and for her interest in the publication of this collection of short stories. Last but not least my husband Saeed Ahmad and my beloved three sons Farakh, Gulraiz and Shahrukh for all their everlasting support.

I first came across the name of Qaisra Shahraz when I bought the anthology

Holding Out

(Crocus, 1988), and read her short story called

A Pair of Jeans

. Its subject caught my attention: a young Muslim woman in England is torn between Western values and her loyalty to her family with its very different attitudes and value system. Teaching it successfully at my university, I found that it met with a very favourable response and gave rise to lively discussions.

I wrote to Qaisra, who invited me to come to Manchester - which I did in the same year that I included her story in my anthology

Writing Women: Twentieth Century Short Stories

(Cornelsen, 1991). And I experienced her overwhelming hospitality. Incidentally, another of Qaisra’s stories

The Elopement

, which I had come across in the anthology

Black and Priceless

(Crocus, 1988), was co-published by myself and two other editors in:

Invitation to Literature

(Cornelsen, 1990).

Qaisra has become a well-known and well-loved figure in Germany, not only in our schools, but also in our Universities of Education. Teachers find her descriptions of her own background and writing engaging and stimulating, and she has visited Germany on a more or less regular basis.

Today it seems remarkable to me that we have known each other for 23 years and never lost touch. I have witnessed a young woman grow into an internationally acclaimed and respected author, who moved beyond short-story writing to try her hand at highly ambitious novels.

The Holy Woman

(2001) and

Typhoon

(2003) won international acclaim, and I felt gratified when she invited me to contribute to the first monograph about her literary output:

The Holy and the Unholy, Critical Essays on Qaisra Shahraz’s Fiction

(2011).

Although she has spent most of her life in England and works professionally as an education consultant and college inspector, I perceive her to be living in both worlds - the British as well as the Pakistani Muslim world. Her short stories may therefore be set in either location, but she peoples them invariably with characters of Pakistani background or origin, like Noor in

Zemindar’s Wife

, the disillusioned village elder in

The City Dwellers

and Samir in

Escape

, lost between his own two worlds of Manchester and Lahore.

I regard Qaisra as an author who is loyal to her faith and at the same time tries to bring home her values to readers of different backgrounds and different faiths - to bridge those two different worlds. She never preaches, but she opens doors to let us see new and unfamiliar scenarios and to meet unexpected characters who invite our response. And I am happy that we have been friends for such a long time.

Dr. Liesel Hermes, Karlsruhe

Former President of the University of Education, Karlsruhe, Germany

“Aren’t you going to the

Zemindar

’s dinner, my son?” Kaniz asked her twenty-year old son, Younis, reading a book at his desk. She waited; fearing his answer. The rest of the family were ready to shoot off to the Zemindar’s

hevali

.

The

Zemindar

, the feudal Landlord, following the century old custom of his family, had invited the fellow villagers for a sumptuous dinner. Since the invitations arrived, a hubbub of excitement had reigned in each household. This morning there was a feverish tension running amongst the young women and girls about clothes, glamour and who would be wearing what. Above all, today they would gain a rare glimpse of their proud, youthful and very beautiful Chaudharani, the

Zemindar’s

wife – what a climax to good feasting. Always, a great honour to be invited to the

Zemindar’s

palatial residence, especially to eat, but what was the occasion this time, quite a few villagers mused, gossiping.

“You go! I need to read!” Younis, studying for a Bachelor of Arts degree at the Lahore Punjab University could not hold back the sarcasm from his voice.

“It will only take an hour or so, my son. Quickly eat and then return home.” Kaniz regretted her words, seeing his face redden.

“Mother, I am not starving! My studies are far more important than eating a sumptuous dinner off the

Zemindar’s

special china plates! You go if you must. You’ve talked about nothing else since the invitation arrived. It makes me sick the hold that he, and the proud bitch of a wife he has, have over you all”. Kaniz stepped back, shocked.

“My son, what terrible language! How can you call the Chaudharani that?”

Troubled, she left her son. Education had changed him. Above all, he had become very abusive when he talked about the

Zemindar

and his wife. Younis hated the feudal system, disliking the feudal clan in their village, their wealth and the power they had over the villagers. Kaniz wondered how the haughty Chaudharani would receive them; still bitterly able to recall queuing up excitedly with the village women under the

hevali’s

veranda. Their simple loving hearts were swelling with warmth to welcome the new wife. She, with one look of disdain from her cold emerald green eyes, dismayed them. They quickly learnt the lesson; she was of a superior breed, they were nothing but country bumpkins. They had no roles in her life, only as servants, inferior mortals to do her bidding. Rebuffed and humiliated, Kaniz and the other women had retreated from the

hevali

and into themselves.

Younis looked out of his bedroom window, with a cynical twist to his lips. The street was packed with men, women and children, all dressed in their very best, hastening towards the

hevali

, a large whitewashed imposing building on the top of the hill. It was and was meant to be different from the rest of the humbler village dwellings. Even men who had migrated out to the West or to the Arab countries, hadn’t been able to build a

khoti

to compete with the splendour of the

hevali

.

Younis returned to his book on Karl Marx and note taking for his seminar. He wondered whether the

Zemindar

would miss his presence.

The object of his thought, Sarfaraz Jhangir, a man of thirty-seven years, was sitting on his horse, on the outskirts of the village, inspecting the sugar cane fields on his land. Apart from a few plots, most of the land around the village belonged to him, and before that to his forefathers. He gained his income from the cash crops that the land produced. Most of the villagers, apart from those who owned the land, worked for him. He paid them good salaries, but the profit from the crops was his, as the owner of the land.

Sarfaraz checked his watch. He’d better get back to the

hevali

, to welcome the villagers. After handing his horse to the stable boy, Sarfaraz crossed the courtyard to make his way to his private quarters. There in his bedroom, he stood still against the door, lips parted. Staring at Noor, the light of his life.

His wife, sitting in front of a large mirror, was making up her face. Her long hair fell in loose auburn waves around her shoulders. With the afternoon sun streaming through the window, it glinted like flames of fire.

He tiptoed across the room to stand behind her, holding her gaze in the mirror and letting his fingers thread through her hair; momentarily closing his eyes, revelling in the sensuous feel of it. Bending down he kissed the bare skin of her shoulders around her neckline, his eyes dipping to the voluptuous curves of her breasts, outlined against the crepe of her tunic.

“Allah Pak, how gorgeous she is!” He marvelled; his heartbeat quickening as it always did when he saw her dressed in her wedding finery and in a state of undress.

His passion was suddenly checked, by the cold glint in her emerald gems for eyes. She was angry with him, as she had been for the past fortnight. Ever since she had heard that he was giving a party for all the villagers. She couldn’t make sense of it. What was the special occasion? This wasn’t the time of Eid or any other festival.

In fact, she was furious. Why was her husband wasting his wealth? The dinner was costing a fortune. It wasn’t a minor affair to feed over two hundred people, providing two meat dishes. The slaughter of dozens of lambs and sheep would stain their

bavarchikhanah

, kitchen. What was worse, it sounded as though Sarfaraz wanted this dinner business to be a regular event.

She had wanted to go to her parents’ home as a sign of protest, but he had insisted that she stay and host the dinner with him, arguing that it wouldn’t be very good for his

Izzat

, his honour, not to have his wife at his side, especially a wife like his, an asset to show off.

By nature she was a proud, haughty woman. Her beauty, wealth, and upbringing as the daughter of a rich influential

Zemindar

, had all contributed to that haughtiness. Today, however, that haughtiness had a dangerous element to it. The last thing she wanted to do was to entertain hordes of village bumpkins. Nevertheless, if she was going to be the hostess at the dinner party, then she had to look the part. She had her reputation at stake. It was almost as if she was going to be put on show – she mustn’t, therefore, disappoint them.

She didn’t!

The village guests were sitting at round tables. All heads and eyes were riveted on Noor as she entered. A hushed silence fell on the courtyard; even the birds seemed to have stopped singing, entranced by her appearance.

Noor walked gracefully to her seat; a tall, elegant, beautiful woman, fully aware of the spell she had cast over her audience. A shadow of a smile played on her full, luscious, glossy lips. Since her teenage years, when she had become aware of her beauty, she knew how to exploit it and to command attention, respect and authority. In her case all three went hand in hand. What she hadn’t realised and wouldn’t have cared about anyway, was that it was her beauty which intimidated people.

She sat down, and let her gaze indolently fan over the groups of people assembled, all gazing at her. She smiled at everyone, but at no one in particular. Manners and breeding had been drilled into her from an early age. The coldness that emanated from her green eyes, and the stiff composed manner she adopted, intimidated her guests and further heightened the barrier between them, her husband, and herself.

The men tried to resist the impulse to keep looking at her. It was wrong and immoral for a man to look at another man’s wife, no matter how attractive she was. The women, on the other hand, didn’t take their eyes off her, nor, for that matter, did they make any pretence to do so. Dinner was one thing, but to be able to feast their eyes on their elegant, beautiful but haughty Chaudharani, their mistress, was an added bonus. They had to admit that she had done justice to her looks and the occasion.

Their eyes kept wandering to her beautiful, well sculptured features. It was almost as if Allah had been carried away when it came to Noor. She was different. They had never seen such beautiful green eyes – cold though they were, nor hair of such colour. It cascaded down in open waves over one shoulder. It was all visible from under the delicate pink chiffon

dupatta

, the scarf which was draped casually around her shoulders and over her head. It formed a becoming frame for her hair and face. Her rounded milky white wrists were covered by delicately designed gold bangles. The women tried to count how many she wore – there were at least two dozen on each arm. Probably she had more gold on her arms than all the village women put together.

The bangles matched the delicately designed beautiful necklace, which lovingly embraced her neck and the ear studs hugging her ears. Her shalwar kameez suit was flowing and classically cut. It had obviously been cut by fine

derzi

, the tailors from the city rather than those in the village. The women’s eyes almost hypnotically wandered from her beautiful long hands with well-manicured and polished nails, to the attractive feet, visible in elegant, and dainty black mules, which showed off the fairness of her skin. It was almost as if they had been kept wrapped in cotton wool. She had probably never been out in the hot afternoon sun in all her life.

They all waited for her to say something. They had already listened to the

Zemindar

welcoming them to the dinner party. The waiters had begun to lay the tables and to place soft drinks and salad bowls on the tables. Somehow the tense, electric atmosphere that had prevailed since the

Zemindar’s

wife had entered, had affected everybody. Nobody spoke, but they waited uneasily for somebody to say something.

Suddenly something did happen. A four-year-old girl, managed to wriggle off her mother’s lap, and dash straight towards the Chaudharani. Everyone was startled out of their unease. How would the Chaudharani react?

Noor too was surprised when this gorgeous four-year-old bounded straight forward towards her lap. Much to the surprise of the onlookers, her luscious pink lips spread out into a broad smile, and she held out her hand to the child. She had always been partial to beauty, in particular to beautiful children. She held onto the child and smiled down at it, but she resisted the urge to pick her up and put her on her lap. Alone, she might have done it, but not here in front of over two hundred people. She didn’t want to be seen giving more favour to one child than to others. It had been bred into her from an early age, that one must treat everybody the same, and never show favouritism amongst the villagers – otherwise they forgot their place, and began to exploit the situation, and it was also unfair.

She could see the mother’s cheeks glowing with happiness and embarrassment. Later that same mother would be boasting to all the other village women, how the Chaudharani had taken to her child. So Noor restrained the impulse to ask the child to sit with her, but the warmth she displayed towards the child had a miraculous effect on the people in the courtyard. They all relaxed. Her eyes were now warm, matching the genuine smile on her lips. Noor took the child as a cue.

Getting up, she spoke! Her voice was attractive, which complimented her physical looks.

“Welcome everybody. I hope you’ll show your appreciation of our hospitality by doing justice to the food, prepared by our clever

halwais

, the chefs.”

The welcome speech was music to the villagers’ ears. Her speech, though formal and short, had brought her closer to them. She told the little girl to return to her mother. The girl, smiling, turned to go to her mother. Noor sat down again, next to her husband, and kept watch over the proceedings. She wanted everything to run smoothly and as planned.

When the food was being served, Noor took her leave. She had done enough! Her husband watched her go. He wished she had stayed a bit longer but he was grateful and couldn’t complain. She could have thrown a tantrum and stayed inside. No, he was married to an intelligent woman, with good breeding, and one who would never let him or his

izzat

down, no matter what she was like in private. She had performed her task much better than he had anticipated.

He hosted the dinner right to the end, talking to each and every family and making small talk. In particular he spoke with Younis’s family. He enquired casually as to why Younis hadn’t come, as he had seen him since he had returned for his summer holidays. Kaniz, Younis’s mother, replied that he wasn’t feeling well. The

Zemindar

naturally made the right response to Younis’s mother, but his mind was buzzing with ideas; he was certain that her son had deliberately not come. Who the hell did Younis think he was anyhow? He was a village upstart, just because he had gained some college certificate. The boy’s arrogance even surpassed that of his wife’s. Did he think that he could challenge the authority of the village

Zemindar

, a person of class, status and wealth? All of Younis’s degrees couldn’t compete with that. Nevertheless it nettled him that Younis had not come. It was a deliberate snub and it troubled him. He wanted men like Younis to be on his side and not opposing him; after all Younis could thwart all his plans!

…ooo000ooo…

In every household that evening, when the villagers returned home, the talk centred not on the dinner, but on the

Zemindar’s

wife. Her beauty and haughtiness were both already subjects of everyday conversation, but now they talked about her amazing warmth. She wasn’t so bad after all, and she was human like anybody else – she too smiled genuinely just like normal people. Now they all looked forward to next week’s dinner, not just because of the wonderful food that they were sure to get, but that they would surely catch another glimpse of their landlady. They wondered what she would be wearing then. As the Chaudharani stayed inside the

hevali

most of the time, and travelled to and fro in a car, it meant that they rarely came in contact with her. It was generally the custom of the rich and high bred families to make their women folk, in particular the young women, inaccessible to the general public. They were too precious to be soiled by coming in contact with ordinary people or people of a lower status. They weren’t to be ogled at by any

Nethu Pethu

, any Tom, Dick or Harry.