A People's Tragedy (161 page)

Read A People's Tragedy Online

Authors: Orlando Figes

104 The war against religion: Red Army soldiers confiscate valuable items from the Semenov Monastery in Moscow, 1923.

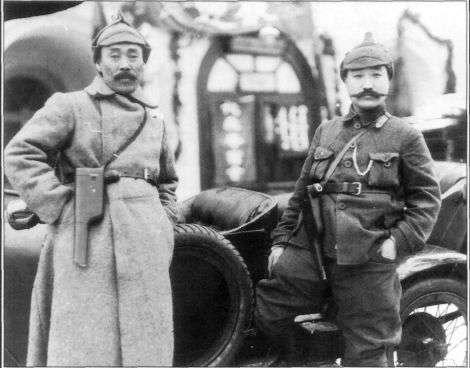

105-6 The revolution expands east.

Above:

the Red Army arrives in Bukhara and explains the meaning of Soviet power to the former subjects of the Emir, September 1920.

Below,

two Bolshevik commissars of the Far East.

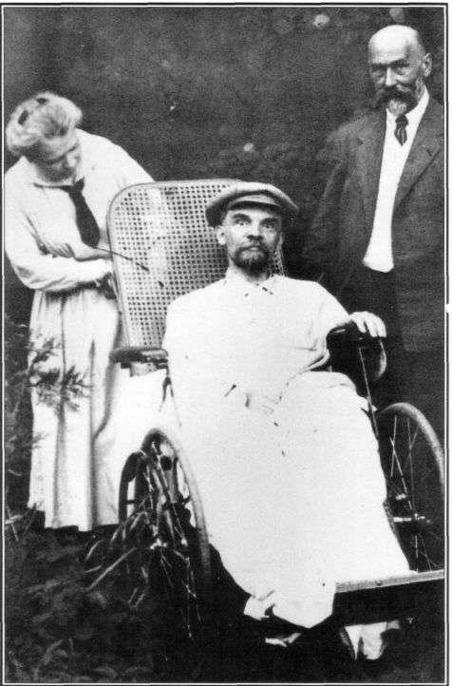

107 The dying Lenin, with one of his doctors and his younger sister Maria Ul'ianova, during the summer of 1923. By the time this photograph was taken, Stalin's rise to power was virtually assured.

brothels, hospitals and clinics, credit and saving associations, even small-scale manufacturers sprang up like mushrooms after the rain. Foreign observers were amazed by the sudden transformation. Moscow and Petrograd, graveyard cities in the civil war, suddenly burst into life, with noisy traders, busy cabbies and bright shop signs filling the streets just as they had done before the revolution. 'The NEP turned Moscow into a vast market place,' recalled Emma Goldman:

Shops and stores sprang up overnight, mysteriously stacked with delicacies Russia had not seen for years. Large quantities of butter, cheese and meat were displayed for sale; pastry, rare fruit, and sweets of every variety were to be purchased. Men, women and children with pinched faces and hungry eyes stood about gazing into the windows and discussing the great miracle: what was but yesterday considered a heinous offence was now flaunted before them in an open and legal manner.'63

But could those hungry people afford such goods? That was the fear of the Bolshevik rank and file. It seemed to them that the boom in private trade would inevitably lead to a widening gap between rich and poor. 'We young Communists had all grown up in the belief that money was done away with once and for all,' recalled one Bolshevik in the 1940s. 'If money was reappearing, wouldn't rich people reappear too? Weren't we on the slippery slope that led back to capitalism? We put these questions to ourselves with feelings of anxiety.' Such doubts were strengthened by the sudden rise of unemployment in the first two years of the NEP. While these unemployed were living on the bread line the peasants were growing fat and rich. 'Is this what we made the revolution for?' one Bolshevik asked Emma Goldman. There was a widespread feeling among the workers, voiced most clearly by the Workers' Opposition, that the NEP was sacrificing their class interests to the peasantry, that the 'kulak' was being rehabilitated and allowed to grow rich at the workers' expense. In 1921—2

literally tens of thousands of Bolshevik workers tore up their party cards in disgust with the NEP: they dubbed it the New Exploitation of the Proletariat.66

Much of this anger was focused on the 'Nepmen', the new and vulgar get-rich-quickly class of private traders who thrived in Russia's Roaring Twenties. It was perhaps unavoidable that after seven years of war and shortages these wheeler-dealers should step into the void. Witness the 'spivs' in Britain after 1945, or, for that matter, the so-called 'mafias' in post-Soviet Russia. True, the peasants were encouraged to sell their foodstuffs to the state and the cooperatives by the offer of cheap manufactured goods in return. But until the socialized system began to function properly (and that was not until the mid-1920s) it remained easier and more profitable to sell them to the 'Nepmen'

instead. If some product was particularly scarce these profiteers were sure to have it — usually because they had bribed some Soviet official. Bootleg liquor, heroin and cocaine — they sold everything. The 'Nepmen' were a walking symbol of this new and ugly capitalism. They dressed their wives and mistresses in diamonds and furs, drove around in huge imported cars, snored at the opera, sang in restaurants, and boasted loudly in expensive hotel bars of the dollar fortunes they had wasted at the newly opened race-tracks and casinos. The ostentatious spending of this new and vulgar rich, shamelessly set against the background of the appalling hunger and suffering of these years, gave rise to a widespread and bitter feeling of resentment among all those common people, the workers in particular, who had thought that the revolution should be about ending such inequalities.

This profound sense of plebeian resentment — of the 'Nepmen', the 'bourgeois specialists', the 'Jews' and the 'kulaks' — remained deeply buried in the hearts of many people, especially the blue-collar workers and the party rank and file. Here was the basic emotional appeal of Stalin's 'revolution from above', the forcible drive towards industrialization during the first of the Five Year Plans. It was the appeal to a second wave of class war against the 'bourgeoisie' of the NER the new 'enemies of the people', the idea of a return to the harsh but romantic spirit of the civil war, that 'heroic period' of the revolution, when the Bolsheviks, or so the legend went, had conquered every fortress and pressed ahead without fear or compromise. Russia in the 1920s remained a society at war with itself — full of unresolved social tensions and resentments just beneath the surface. In this sense, the deepest legacy of the revolution was its failure to eliminate the social inequalities that had brought it about in the first place.

16 Deaths and Departures

i Orphans of the Revolution

'No, I am not well,' Gorky wrote to Romain Rolland on his arrival in Berlin — 'my tuberculosis has come back, but at my age it is not dangerous. Much harder to bear is the sad sickness of the soul — I feel very tired: during the past seven years in Russia I have seen and lived through so many sad dramas — the more sad for not being caused by the logic of passion and free will but by the blind and cold calculation of fanatics and cowards ... I still believe fervently in the future happiness of mankind but I am sickened and disturbed by the growing sum of suffering which people have to pay as the price of their fine hopes.'1 Death and disillusionment lay behind Gorky's departure from Russia in the autumn of 1921. So many people had been killed in the previous four years that even he could no longer hold firm to his revolutionary hopes and ideals. Nothing was worth such human suffering.

Nobody knows the full human cost of the revolution. By any calculation it was catastrophic. Counting only deaths from the civil war, the terror, famine and disease, it was something in the region of ten million people. But this excludes the emigration (about two million) and the demographic effects of a hugely reduced birth-rate —

nobody wanted children in these frightful years — which statisticians say would have added up to ten million lives.* The highest death rates were among adult men — in Petrograd alone there were 65,000 widows in 1920 — but death was so common that it touched everyone. Nobody lived through the revolutionary era without losing friends and relatives. 'My God how many deaths!' Sergei Semenov wrote to an old friend in January 1921. 'Most of the old men — Boborykin, Linev, Vengerov, Vorontsov, etc., have died. Even Grigory Petrov has disappeared — how he died is not known, we can only say that it probably was not from joy at the progress of socialism. What hurts especially is not even knowing where one's friends are buried.' How death could affect a single family is well illustrated by the Tereshchenkovs. Nikitin

* It also excludes the reduced life expectancy of those who survived due to malnutrition and disease. Children born and brought up in these years were markedly smaller than older cohorts, and 5 per cent of all new-borns had syphilis (Sorokin,

Sovremennoe,

16, 67).

Tereshchenkov, a Red Army doctor, lost both his daughter and his sister to the typhus epidemic in 1919; his eldest son and brother were killed on the Southern Front fighting for the Red Army in that same year; his brother-in-law was mysteriously murdered.

Nikitin's wife was dying from TB, while he himself contracted typhus. Denounced by the local Cheka (like so many of the rural intelligentsia) as 'enemies of the people', they lost their town house in Smolensk and were living, in 1920, on a small farm worked by their two surviving sons — Volodya, fifteen, and Misha, thirteen.2

To die in Russia in these times was easy but to be buried was very hard. Funeral services had been nationalized, so every burial took endless paperwork. Then there was the shortage of timber for coffins. Some people wrapped their loved ones up in mats, or hired coffins — marked 'PLEASE RETURN' — just to carry them to their graves. One old professor was too large for his hired coffin and had to be crammed in by breaking several bones. For some unaccountable reason there was even a shortage of graves —

would one believe it if this was not Russia? — which left people waiting several months for one. The main morgue in Moscow had hundreds of rotting corpses in the basement awaiting burial. The Bolsheviks tried to ease the problem by promoting free cremations.

In 1919 they pledged to build the biggest crematorium in the world. But the Russians'

continued attachment to the Orthodox burial rituals killed off this initiative.3

Death was so common that people became inured to it. The sight of a dead body in the street no longer attracted attention. Murders occurred for the slightest motive — stealing a few roubles, jumping a queue, or simply for the entertainment of the killers. Seven years of war had brutalized people and made them insensitive to the pain and suffering of others. In 1921 Gorky asked a group of soldiers from the Red Army if they were uneasy about killing people. 'No they were not. "He has a weapon, I have a weapon, so we are equal; what's the odds, if we kill one another there'll be more room in the land." '

One soldier, who had also fought in Europe in the First World War, even told Gorky that it was easier to kill a Russian than a foreigner. 'Our people are many, our economy is poor; well, if a hamlet is burnt, what's the loss? It would have burnt down itself in due course.' Life had become so cheap that people thought little of killing one another, or indeed of others killing millions in their name. One peasant asked a scientific expedition working in the Urals during 1921: 'You are educated people, tell me then what's to happen to me. A Bashkir killed my cow, so

of course

I killed the Bashkir and then I took the cow away from his family. So tell me: shall I be punished for the cow?' When they asked him whether he did not rather expect to be punished for the murder of the man, the peasant replied: 'That's nothing, people are cheap nowadays.'