A People's Tragedy (62 page)

Read A People's Tragedy Online

Authors: Orlando Figes

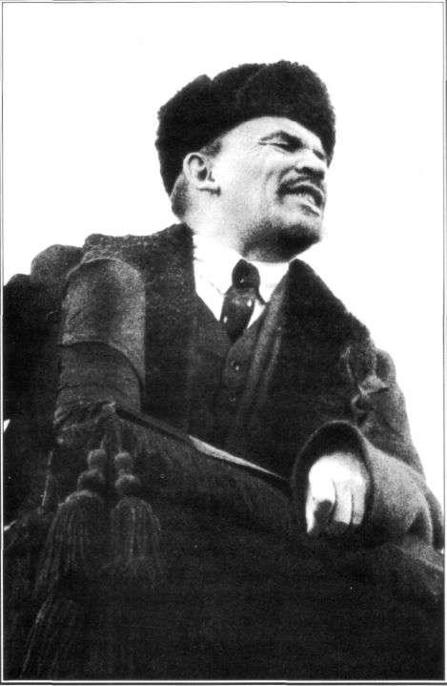

35 Lenin harangues the crowd, 1918. The photographer was Petr Otsup, one of the pioneers of the Soviet school of photo-journalism.

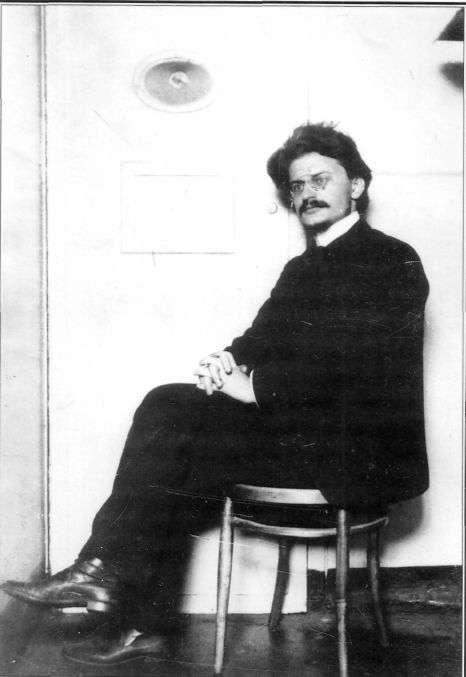

36 Trotsky in the Peter and Paul Fortress in 1906. Trotsky was a dapper dresser, even when in jail. Here, in the words of Isaac Deutscher, he looks more like 'a prosperous western European

fin-de-siecle

intellectual just about to attend a somewhat formal reception [than] a revolutionary awaiting trial in the Peter and Paul Fortress. Only the austerity of the bare wall and the peephole in the door offer a hint of the real background.'

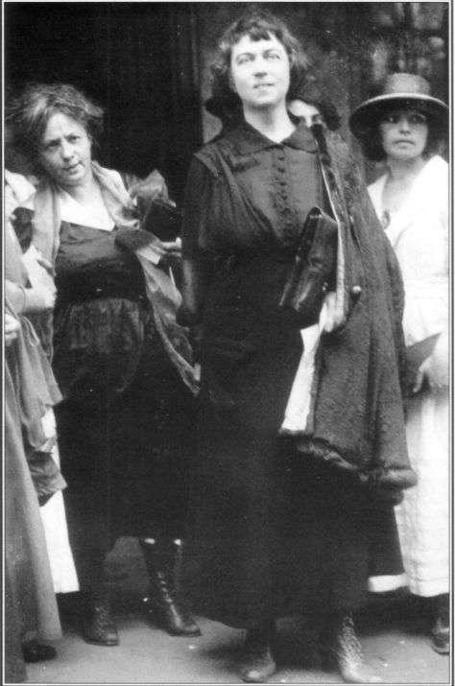

37 Alexandra Kollontai in 1921, when she threw her lot in with the Workers'

Opposition. Kollontai's break with Lenin was especially significant because she had been the only senior Bolshevik to support his

April Theses

from the start.

to bid him farewell at the station, and the Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna was put under house arrest for trying to.

Contrary to the intentions of the conspirators, Rasputin's death drew Nicholas closer to his grief-stricken wife. He was now more determined than ever to resist all advocates of reform. He even banished four dissident grand dukes from Petrograd. As the revolution drew nearer, he retreated more and more into the quiet life of his family at Tsarskoe Selo, cutting off all ties with the outside world and even the rest of the court. There was no customary exchange of gifts between the imperial couple and the Romanovs at the dynasty's final Christmas of 1916.

Rasputin's embalmed body was finally buried outside the palace at Tsarskoe Selo on a freezing January day in

1917.

After the February Revolution a group of soldiers exhumed the grave, packed up the corpse in a piano case and took it off to a clearing in the Pargolovo Forest, where they drenched it with kerosene and burned it on top of a pyre. His ashes were scattered in the wind.

iii

From the Trenches to the Barricades

Trotsky's boat sailed into New York harbour on a cold and rainy Sunday evening in January 1917. It had been a terrible crossing, seventeen stormy days in a small steamboat from Spain, and the revolutionary leader now looked haggard and tired as he disembarked on the quayside before a waiting crowd of comrades and pressmen. His mood was depressed. Expelled as an anti-war campaigner from France, his adopted home since 1914, he felt that 'the doors of Europe' had been finally 'shut behind' him and that, like his fellow passengers on board the

Montserrat,

a motley bunch of deserters, adventurers and undesirables forced into exile, he would never return. 'This is the last time', he wrote on New Year's Eve as they sailed past Gibraltar, 'that I cast a glance on that old

canaille

Europe.'64 It was a mark of the party's frustration that three of the leading Social Democrats — Trotsky, Bukharin and Kollontai — should find themselves together in New York, 5,000 miles from Russia, on the eve of the 1917

Revolution. Nikolai Bukharin had arrived from Oslo during the previous autumn and taken over the editorship of

Novyi mir

(New World), the leading socialist daily of the Russian emigre community. At the age of twenty-nine, he had already established himself as a leading Bolshevik theoretician and squabbled with Lenin on several finer points of party ideology, before leaving Europe with the claim that 'Lenin cannot tolerate any other person with brains.' Short and slight with a boyish, sympathetic face and a thin red beard, he was waiting for Trotsky on the quayside. Unlike the dogmatic Lenin, who had heaped abuse on

the left-wing Menshevik, he was keen to include Trotsky in a broad socialist campaign against the war. He had known the Trotskys slightly in Vienna and shared their love for European culture. He greeted them with a bear hug and immediately began to tell them, as Trotskys wife recalled, 'about a public library which stayed open late at night and which he proposed to show us at once'. Although it was late and the Trotskys were very tired, they were dragged across town 'to admire his great discovery'.65 Thus began the close but ultimately tragic friendship between Trotsky and Bukharin.

Trotsky saw less of Alexandra Kollontai. She spent much of her time in the New Jersey town of Paterson, where her son had settled to avoid the military draft. This was her second American trip. The year before she had toured the country proselytizing Lenin's views on the war. An ebullient and emotional woman, prone to fall in love with young men and Utopian ideas, she had thrown herself into the Bolshevik cause with all the fanaticism of the newly converted. 'Nothing was revolutionary enough for her,' recalled a Trotsky still bitter fourteen years later at her denunciation of him, in a letter to Lenin, as a waverer on the war.66 Trotsky was closer to the Bolsheviks than Kollontai appreciated, and the motives for his leftward progression from the Mensheviks were similar to her own.

Like many of the exiled revolutionaries, Trotsky and Kollontai were both driven by their commitment to international socialism. Fluent in several European languages and steeped in classical culture, they saw themselves less as Russians — Kollontai was half-Finnish, half-Ukrainian, while Trotsky was a Jew — than as comrades of the international cause. They were equally at home in the British Museum, in the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, or in the cafes of Vienna, Zurich and Berlin, as they were in the underground revolutionary cells of St Petersburg. The Russian Revolution was for them no more than a part of the international struggle against capitalism.

Germany, the home of Marx and Engels, was the intellectual centre of their world. 'For us', recalled Trotsky, 'the German Social Democracy was mother, teacher and living example. We idealized it from a distance. The names of Bebel and Kautsky were pronounced reverently.'67

But the German spell had been abruptly broken in August 1914. The Social Democrats rallied behind the Kaiser in support of the war campaign. For the leaders of the Russian Revolution, who thought of themselves as disciples of the European Marxist tradition, the 'betrayal of the Germans' was, as Bukharin put it, 'the greatest tragedy of our lives'.

Lenin, then in Switzerland, had been so convinced of the German comrades'

commitment to the international cause that he had at first dismissed the press reports of their support for the war as part of a German plot to deceive the socialists abroad.

Trotsky, who had heard the news on his way to Zurich, was shocked by it 'even more than the declaration

of war'. As for Kollontai, she had been present in the Reichstag to witness her heroes give their approval to the German military budget. She had watched in disbelief as they lined up one by one, some of them even dressed in army uniforms, to declare their allegiance to the Fatherland. 1 could not believe it,' she wrote in her diary that evening;

'I was convinced that either they had all gone mad, or else I had lost my mind.' After the fatal vote had been taken she had run out in distress into the lobby — only to be accosted by one of the socialist deputies who angrily asked her what a Russian was doing inside the Reichstag building. It had suddenly dawned upon her that the old solidarity of the International had been buried, that the socialist cause had been lost in chauvinism, and 'it seemed to me', she wrote in her diary, 'that all was now lost'.68

It was not just their European comrades who had abandoned the international cause.

Most Russian socialists had also rallied to the cry of their Fatherland. The Menshevik Party, home and school of both Trotsky and Kollontai, was split between a large Defensist majority, led by the elderly Plekhanov, which supported the Tsar's war effort on the grounds that Russia had the right to defend itself against a foreign aggressor, and a small Internationalist minority, led by Martov, which favoured a democratic peace campaign. The SR Party was similarly divided, with the Defensists placing Allied military victory before revolution, and Internationalists advocating revolution as the only way to end what they saw as an imperialist war in which all the belligerents were equally to blame. These divisions were to cripple both parties during the crucial struggles for power in 1917. At their heart lay a fundamental difference of world-view between those, on the one hand, who acknowledged the legitimacy of nation states and the inevitability of conflict between them, and those, on the other, who placed class divisions above national interests. Feelings on this could run high. Gorky, for example, who considered himself an ardent Internationalist, broke off all relations with his adopted son, Zinovy Peshkov, when he volunteered for the French Legion. Gorky even refused to write to him when his hand was shot off whilst leading an attack on the German positions during his first battle.* To the patriots, the Internationalists'

opposition to the war seemed dangerously close to helping the enemy. To the Internationalists, the patriots' call to arms

* Zinovy Peshkov (1884-1966) was the brother of Yakov Sverdlov, the Bolshevik leader and first Soviet President. After recovering from his wound, he enlisted in the French military intelligence. He supported Kornilov's movement against the Provisional Government. In 1918 he joined Semenov's anti-Bolshevik army in the Far East and then Kolchak's White government in Omsk. In 1920 he was sent to the Crimea as a French military agent in Wrangel's government and left Russia with Wrangel's army. He later became a close associate of Charles de Gaulle and a prominent French politician. What is strange is that until 1933 Peshkov maintained good relations with Gorky in Russia, and that Gorky knew about his intelligence activities. See Delmas, Legionnaire et diplomate'.

seemed tantamount to adopting the slogan 'Workers of the World, Seize Each Other by the Throat!'69

The Bolsheviks were the only socialist party to remain broadly united in their opposition to the war, although they too had their own defensists during the early days before Lenin had imposed his views. His opposition to the war was uncompromising.

Unlike the Menshevik and SR Internationalists, who sought to bring the war to an end through peaceful demonstration and negotiation, Lenin called on the workers of the world to use their arms against their own governments, to end the war by turning it into a series of civil wars, or revolutions, across the whole of Europe. It was to be a 'war against war'.

For Trotsky and Kollontai, who had both come to see the Russian revolution as part of a European-wide struggle against imperialism, there was an iron logic at the heart of Lenin's slogan which increasingly appealed to their own left-wing Menshevik internationalism. To begin with, in the first year of the war, both had similar doubts about the Bolshevik leader. Whereas Lenin had argued that Russia's defeat would be a lesser evil' than that of the more advanced Germany, they opposed the whole idea of military victors and losers. The dispute, though minor in itself, related to a broader difference of opinion. Lenin had recently come to stress the revolutionary potential of nationalist movements within colonial systems, and he argued that Russia's defeat would help to bring about the collapse of the Tsarist Empire. But Trotsky and Kollontai (like Bukharin for that matter) believed that the nation-state would soon become a thing of the past and thus denied it as a revolutionary force. Nor could they quite yet bring themselves to embrace the Leninist call for a 'war against war'. They preferred the pacifist slogans of their old friends and allies among the Menshevik Internationalists.