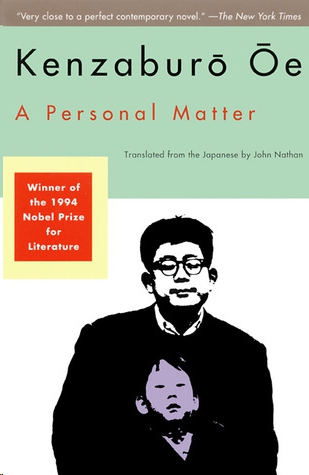

A Personal Matter

Authors: Kenzaburo Oe

A PERSONAL MATTER

K

ENZABURO

O

Ë

was born in 1935, in Ose village in Shikoku, Western Japan. His first stories were published in 1957, while he was still a student. In 1958 he won the coveted Akutagawa prize for his novella

The Catch

. His first novel was published in 1958—

Pluck the Flowers, Gun the Kids.

In 1959 the publication of a novel,

Our Age,

brought the critics down on Oë’s head: they deplored the dark pessimism of the book at a time supposed to be the new, bright epoch in modern Japanese history. During the anti-security riots in 1960, Oë traveled to Peking, representing young Japanese writers and there met with Mao.

In 1961, he traveled in Russia and Western Europe, meeting with Sartre in Paris and writing a series of essays about youth in the West. In 1962 he published the novel

Screams;

in 1963,

The Perverts,

and a book memorializing Hiroshima called simply,

Hiroshima Notes.

In 1964, Oë published two novels,

Adventures in Daily Life

and

A Personal Matter,

for which he won the Shinchosha Literary Prize. In the summer of 1965 he participated in the Kissinger International Seminar at Harvard. Oë’s novel

Football in the First Year of Mannen,

completed in 1967, won the Tanizaki Prize.

Books by Kenzabur

ō

Ō

e

published by Grove Press

Somersault

Rouse Up O Young Men of the New Age!

A Personal Matter

The Crazy Iris and Other Stories

Hiroshima Notes

Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids

A Quiet Life

Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness

by Kenzaburo Oë

Translated from the Japanese by John Nathan

Copyright © 1969 by Grove Press, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

Originally published as

Kojinteki Na Taiken,

copyright © Kenzaburo

Oë, 1964, by Shinchosa, Tokyo, Japan

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 68-22007

eBook ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9544-9

Grove Press

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

This translation is for “Pooh”

T

HERE

is a tradition in Japan: no one takes a writer seriously while he is still in school. Perhaps the only exception has been Kenzaburo Oë. In 1958, a student in French Literature at Tokyo University, Oë won the Akutagawa Prize for a novella called

The Catch

(about a ten-year-old Japanese boy who is betrayed by a Negro pilot who has been shot down over his village), and was proclaimed the most promising writer to have appeared since Yukio Mishima.

Last year, to mark his first decade as a writer, Oë’s collected works were published—two volumes of essays, primarily political (Oë is an uncompromising spokesman for the New Left of Japan), dozens of short stories, and eight novels, of which the most recent is

A Personal Matter.

Oë’s industry is dazzling. But even more remarkable is his popularity, which has continued to climb: to date, the

Complete Works,

in six volumes, has sold nine hundred thousand copies. The key to Oë’s popularity is his sensitivity to the very special predicament of the postwar generation; he is as important as he is because he has provided that generation with a hero of its own.

On the day the Emperor announced the Surrender in August 1945, Oë was a ten-year-old boy living in a mountain village. Here is how he recalls the event:

“The adults sat around their radios and cried. The children gathered outside in the dusty road and whispered their bewilderment. We were most confused and disappointed by the fact that the Emperor had spoken in a

human

voice, no different from any adult’s. None of us understood what he was saying, but we all had heard his voice. One of my friends could even imitate it cleverly. Laughing, we surrounded him—a twelve-year-old in grimy shorts who spoke with the Emperor’s voice. A minute later we felt afraid. We looked at one another; no one spoke. How could we believe that an august presence of such awful power had become an ordinary human being on a designated summer day?”

Small wonder that Oë and his generation were bewildered. Throughout

the war, a part of each day in every Japanese school was devoted to a terrible litany. The Ethics teacher would call the boys to the front of the class and demand of them one by one what they would do if the Emperor commanded them to die. Shaking with fright, the child would answer: “I would die, Sir, I would rip open my belly and die.” Students passed the Imperial portrait with their eyes to the ground, afraid their eyeballs would explode if they looked His Imperial Majesty in the face. And Kenzaburo Oë had a recurring dream in which the Emperor swooped out of the sky like a bird, his body covered with white feathers.

The emblematic hero of Oë’s novels, in each book a little older and more sensible of his distress, has been deprived of his ethical inheritance. The values that regulated life in the world he knew as a child, however fatally, were blown to smithereens at the end of the war. The crater that remained is a gaping crater still, despite imported filler like Democracy. It is the emptiness and enervation of life in such a world, the frightening absence of continuity, which drive Oë’s hero beyond the frontiers of respectability into the wilderness of sex and violence and political fanaticism. Like Huckleberry Finn—Oë’s favorite book!—he is impelled again and again to “light out for the territory.” He is an adventurer in quest of peril, which seems to be the only solution to the deadly void back home. More often than not he finds what he is looking for, and it destroys him.

A word about the language of

A Personal Matter.

Oë’s style has been the subject of much controversy in Japan. It treads a thin line between artful rebellion and mere unruliness. That is its excitement and the reason why it is so very difficult to translate. Oë consciously interferes with the tendency to vagueness which is considered inherent in the Japanese language. He violates its natural rhythms; he pushes the meanings of words to their furthest acceptable limits. In short, he is in the process of evolving a language all his own, a language which can accommodate the virulence of his imagination. There are critics in Japan who take offense. They cry that Oë’s prose “reeks of butter,” which is a way of saying that he has alloyed the purity of Japanese with constructions from Western languages. It is true that Oë’s style assaults traditional notions of what the genius of the language is. But that is to be expected: his entire stance is an assault on traditional values. The protagonist of his fiction is seeking his identity in a perilous wilderness, and it is fitting that his language should be just what it is—wild, unresolved, but never less than vital.

March, 1968

B

IRD

, gazing down at the map of Africa that reposed in the showcase with the haughty elegance of a wild deer, stifled a short sigh. The salesgirls paid no attention, their arms and necks goosepimpled where the uniform blouses exposed them. Evening was deepening, and the fever of early summer, like the temperature of a dead giant, had dropped completely from the covering air. People moved as if groping in the dimness of the subconscious for the memory of midday warmth that lingered faintly in the skin: people heaved ambiguous sighs. June—half-past six: by now not a man in the city was sweating. But Bird’s wife lay naked on a rubber mat, tightly shutting her eyes like a shot pheasant falling out of the sky, and while she moaned her pain and anxiety and expectation, her body was oozing globes of sweat.

Shuddering, Bird peered at the details of the map. The ocean surrounding Africa was inked in the teary blue of a winter sky at dawn. Longitudes and latitudes were not the mechanical lines of a compass: the bold strokes evoked the artist’s unsteadiness and caprice. The continent itself resembled the skull of a man who had hung his head. With doleful, downcast eyes, a man with a huge head was gazing at Australia, land of the koala, the platypus, and the kangaroo. The miniature Africa indicating population distribution in a lower corner of the map was like a dead head beginning to decompose; another, veined with transportation routes, was a skinned head with the capillaries painfully exposed. Both these little Africas suggested unnatural death, raw and violent.

“Shall I take the atlas out of the case?”

“No, don’t bother,” Bird said. “I’m looking for the Michelin road maps of West Africa and Central and South Africa.” The girl bent over

a drawer full of Michelin maps and began to rummage busily. “Series number 182 and 185,” Bird instructed, evidently an old Africa hand.

The map Bird had been sighing over was a page in a ponderous, leather-bound atlas intended to decorate a coffee table. A few weeks ago he had priced the atlas, and he knew it would cost him five months’ salary at the cram-school where he taught. If he included the money he could pick up as a part-time interpreter, he might manage in three months. But Bird had himself and his wife to support, and now the existence on its way into life that minute. Bird was the head of a family!

The salesgirl selected two of the red paperbound maps and placed them on the counter. Her hands were small and soiled, the meagerness of her fingers recalled chameleon legs clinging to a shrub. Bird’s eye fell on the Michelin trademark beneath her fingers: the toadlike rubber man rolling a tire down the road made him feel the maps were a silly purchase. But these were maps he would put to an important use.

“Why is the atlas open to the Africa page?” Bird asked wistfully. The salesgirl, somehow wary, didn’t answer. Why

was

it always open to the Africa page? Did the manager suppose the map of Africa was the most beautiful page in the book? But Africa was in a process of dizzying change that would quickly outdate any map. And since the corrosion that began with Africa would eat away the entire volume, opening the book to the Africa page amounted to advertising the obsoleteness of the rest. What you needed was a map that could never be outdated because political configurations were settled. Would you choose America, then? North America, that is?

Bird interrupted himself to pay for the maps, then moved down the aisle to the stairs, passing with lowered eyes between a potted tree and a corpulent bronze nude. The nude’s bronze belly was smeared with oil from frustrated palms: it glistened wetly like a dog’s nose. As a student, Bird himself used to run his fingers across this belly as he passed; today he couldn’t find the courage even to look the statue in the face. Bird had glimpsed the doctor and the nurses scrubbing their arms with disinfectant next to the table where his wife had been lying naked. The doctor’s arms were matted with hair.

Bird carefully slipped his maps into his jacket pocket and pressed them against his side as he pushed past the crowded magazine counter and headed for the door. These were the first maps he had purchased for actual use in Africa. Uneasily he wondered if the day would ever come

when he actually set foot on African soil and gazed through dark sunglasses at the African sky. Or was he losing, this very minute, once and for all, any chance he might have had of setting out for Africa? Was he being forced to say good-by, in spite of himself, to the single and final occasion of dazzling tension in his youth? And what if I am? There’s not a thing in hell I can do about it!