A Place of My Own (12 page)

Authors: Michael Pollan

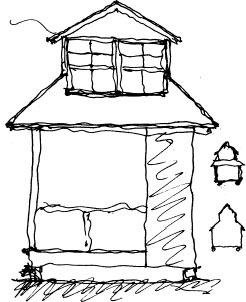

Still working in ink, Charlie sketched what looked like a miniature bungalow with a boxy tower rising up through the middle of its roof to form a second, parallel gable above it, like so:

“Well, he’s definitely his own guy,” Charlie said, drumming his Uniball fine-point on the edge of his drafting table as he appraised the elevation. It did seem vaguely anthropomorphic, with the makings of a strong face. But I wondered if maybe it wasn’t too public a face—the kind you’d expect to meet in a village, or in a campground like Nonquit, but perhaps not alone in the woods.

Charlie said it was too soon to tell. “At a certain point, you have to start getting real about a scheme—start drawing it in elevation with actual dimensions and roof pitches. That’s when an idea that might seem to work in a rough drawing can take on a whole new personality—or fall apart.” Now Charlie switched to pencil, drawing to scale a very precise set of parallel roof lines, one directly above the other. First he tried the same fairly shallow thirty-degree roof pitch our house had, thinking that this might set up a dialogue between the two buildings. But it soon became clear that this pitch would not give me enough headroom upstairs without making the tower so tall as to overwhelm the rest of the building. Charlie chuckled at the monstrosity he’d drawn.

He tried a few other roof pitches, subtracted a few inches from the clearance beneath the second story (“Just for an experiment let’s try six-six, make it nice and cozy under there”), and lengthened the eaves below in order to beef up the lower section relative to the tower. Drafting now was a matter of feeding new angles and measurements into the scheme and then seeing what kind of elevation the geometry came back with; it seemed as though a certain amount of control had passed from Charlie to the drawing process itself, which was liable to produce wholly unexpected results depending on the variables he fed into it. At a pitch of forty-five degrees, for example, the interior of the tower suddenly began to work. “You know, this could be kind of fantastic in here,” Charlie said, brightening as he drew in plan a three-sided desk commanding a 270-degree view. “Sort of like being up on the bridge of a ship—or in your tree house.” But when he turned to the elevation it seemed to have undergone a complete change of personality. No longer a funky campground bungalow, the building had gone back in time half a century and acquired a somewhat Gothic-Victorian aspect, with its steeply pitched roof and slender, upward-thrusting tower. A woodland setting now seemed to suit this house, it was true, but unfortunately it was the woods of the Brothers Grimm: The elevation now suggested a gingerbread cottage. It had gotten cute. Charlie scowled at the drawing. “It’s a hobbit house!”

But the tower scheme had its own momentum now, so Charlie kept at it, playing with the elevation while trying to keep the plan more or less intact, deploying a whole bag of tricks to rid the building of its fairy-tale associations and balance the relative weight of top and bottom. He abbreviated the eaves, beefed up the timbers below while lightening them above, overthrew the symmetry of the façade, and drew in a series of unexpectedly big windows, all of which served to undercut the house’s “hobbitiness.” By the time we decided to break for lunch, the elevation had lost any trace of cuteness, which Charlie clearly felt was the peril in designing such a miniature building. “This is starting to look like something,” Charlie declared at last, by which of course he meant exactly the opposite: The building no longer looked like anything you could readily give a name to—neither bungalow nor gingerbread cottage. The building was once again its own guy. Whether it was

my

guy neither of us felt quite sure. So we decided to put the drawing away for a while, see how it looked to us in a few days.

By now, Charlie and I had traveled pretty far down this particular road, having invested so much work in the tower scheme. But as I drove home to Connecticut later that afternoon, I began to have doubts about it. Mainly I wondered if the building wasn’t getting too big and complicated. My shack in the woods had turned into a two-story house, and I wasn’t sure if it was something I could afford, much less build myself; it certainly didn’t look inexpensive or idiot-proof. When I got home that evening, I walked out to the site, and recalled Charlie’s remark about propriety as I tried to imagine the building in place. Out here on this wooded, rocky hillside, in the middle of this fallen-down farm, it seemed clear that the building he’d drawn would call too much attention to itself. In this particular context, it lacked propriety. Charlie had devised a scheme that would give me everything I’d asked for, it was true, but perhaps that was the problem. Somehow, the building seemed to be getting away from us.

Charlie phoned me first. “I’m starting all over,” he announced, much to my relief. “There’s no reason we can’t get the things you want here—a couple of distinct spaces, a desk, a daybed, a stove, and some kind of porch—without going to two stories.” Drawing the tower scheme had been a valuable exercise, Charlie said. It had helped him to think through all the programmatic elements by getting them down on paper. But now he wanted to go back to the basic eight-by-thirteen rectangle, see if he couldn’t figure out some way to condense all the elements and patterns I wanted into that frame.

“We need to tame this thing—impose some tighter rules. That usually produces better architecture anyway. I can’t lose sight of the basic simplicity of our program here: it’s a hut in the woods, a place for you to work. It is not a second house.”

He started talking about a four-by-eight-foot playhouse he was building for his boys in Tamworth, New Hampshire, where he spent weekends in a converted chicken coop that had been in his family for three generations. The playhouse, which was in the woods up behind the house, consisted of four gigantic timber corner posts set on boulders and crowned with a gable roof framed out of undressed birch logs.

“We could do something like that here: a primitive hut, basically, with a post-and-beam frame. That way, the walls don’t bear any load, which gives us a lot of freedom. We could do some walls thick, others thin. I could even work out some sort of removable wall system, or perhaps windows that disappear into the walls, or up into the ceiling, so that in the summer the whole building turns into a porch.”

Charlie seemed full of ideas now, some of them—like the disappearing windows—sounding fairly complex, and others so primitive as to be worrisome. For example, he wasn’t sure that my building needed a foundation. We could just sink pressure-treated corner posts into the ground, or maybe seat the whole building on four boulders, like his boys’ playhouse. Wouldn’t the frost heave the boulders every winter? That’s no big deal, he said; you rent a house jack and jack the building up in the spring. Charlie was bringing a very different approach to the project now, trying radically to simplify it, to get it back to first principles after the complications of the tower scheme. Which was fine with me, though I told him that I definitely did not want a building that had to be jacked up every April.

From our conversations, I knew that the primitive hut was a powerful image for Charlie, as indeed it has been for many architects at least since the time of Vitruvius. Almost all of the classic architecture treatises I’d read—by Vitruvius, Alberti, Laugier and, more recently, Le Corbusier and Wright—start out with a vivid account of the building of the First Shelter, which serves these author-architects as a myth of architecture’s origins in the state of nature; it also provides a theoretical link between the work of building and the art of architecture. Depending on the author, the primal shelter might be a tent or cave or a wooden post-and-beam hut with a gable roof. More often than not, the architect proceeds to draw a direct line of historical descent from his version of the primitive hut to the style of architecture he happens to practice, thereby implying that this kind of building alone carries nature’s seal of approval. If an architect favors neoclassical architecture over Gothic, for example, chances are his primitive hut will bear a close resemblance to a Greek temple built out of tree trunks.

Literature has its primitive huts too—think of Robinson Crusoe’s or Thoreau’s: simple dwellings for not-so-simple characters who find in such a building a good vantage point from which to cast a gimlet eye upon society. The sophisticate’s primitive hut becomes a tool with which to explore civilized man’s relation to nature and criticize whatever in the contemporary scene strikes the author as artificial or decadent. The idea, in literature and architecture alike, seems to be that a decadent society or style of building can be renewed and refreshed by closer contact with nature, by a return to the first principles and truthfulness embodied in the primitive hut.

For Charlie, the appeal of the hut seemed a good deal less ideological than all that. To him, the image bespoke plain, honest structure; an architecture made out of the materials at hand; a simple habitation carved out of the wilderness; and an untroubled relationship to nature. He had told me about reading the eighteenth-century

philosophe

Marc-Antoine Laugier’s

Essay on Architecture

in architecture school and coming across the etching of a primitive hut on its frontispiece: Charles Eisen’s “Allegory of Architecture Returning to its Natural Model,” which depicts four trees in a rectangle, their branches knitted together to form a leafy, sheltering gable above. “It’s a completely romantic idea,” Charlie said. “But it’s kind of wonderful, too, the image of these four trees giving themselves up to us as the four corners of a shelter—this dream of a perfect marriage between man and nature.”

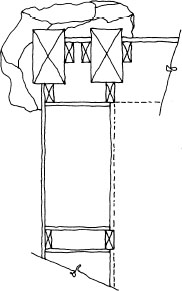

A few weeks later, I received a somewhat cryptic fax from Charlie:

When I reached him late that afternoon, he sounded excited. “So what do you think?” I confessed I didn’t really understand the drawing.

“Oh. Well, what you’ve got there is the detail for the southwest corner of your building. I’ve been working on it for a week, and this morning it finally came together.”

The corner detail?

“No, the whole scheme.”

I asked when I could see the rest of it.

“This detail’s all I’ve drawn so far. But that’s our

parti

, right there—the solution to the problem, in a nutshell. The rest should be fairly easy.”

I still didn’t get it.

“See, the problem I’ve been having with this hut all along is with the thickness of the corner posts.” Charlie was deep inside the new scheme now, and his explanation came in a rush. “Basically, the idea is to do thick walls on the long sides, thin ones front and back. What this does is give the building a strong directionality—it becomes almost a kind of chute, funneling all that space coming down through our site toward the pond.”

He proceeded to explain how the thickness of the posts set up the thickness of our interior walls, which meant the posts would have to be a foot square at a minimum if the walls were going to work as bookshelves. But in fact they had to be a couple of inches thicker than that, since he wanted them to “come proud” of the walls—stand out from the building’s skin, in order to retain their “postness.”

“So already we’re up to fifteen, sixteen inches square, which is one fat post. I tried drawing it

—way

too chunky. You’d need a crane to haul it out there.

“But what if instead I go to a

pair

of posts, six by six, say, with three or four inches of wall between them? That gives me my fifteen inches easily, but without any of that chunkiness.” A single fat corner post would also have suggested that all four of our walls were equally thick, he explained, while a pair of posts at each corner in front would imply that only the long walls directly behind them are thick; by comparison the short walls between the double posts at either end will seem thin, an impression he planned to underscore by filling them with glass.

“There was one more piece of the puzzle, though, which didn’t hit me till this morning. Instead of two square posts, what if I go to six-by-tens and run them lengthwise? This way our corner could articulate the directionality of the building at the same time it sets up the whole idea of thick versus thin walls—enclosure one way, openness the other. That’s what I mean about the whole

parti

being right here in a nutshell.”