A Place of My Own (23 page)

Authors: Michael Pollan

We braced the gable with a pair of two-by-fours, and broke for lunch.

It was imperative we get the ridge pole up before the day was out; without it, an errant gust was liable to make a sail of our gable assembly, bring the whole thing crashing down. After lunch we raised the second gable without incident and took a field measurement to determine the precise length of the ridge pole: 13’ 9¼”. This turned out to be a couple of inches less than the dimension shown on Charlie’s plan, but then at this point the building had its own reality, of which our mistakes formed a necessary part.

Don, the six-and-a-half-foot friend I’d recruited for the event, arrived as Joe and I were preparing to mark and cut the gorgeous length of knot-free fir we’d selected for the building’s spine. This timber too had come from Oregon, according to the stencil on its flank. My tentativeness handling such a piece of wood had vanished; I felt well acquainted with fir—if not quite friend, not foe either. I took up the circular saw, found my mark, and worked the blade through the familiar wood flesh, breathing in its sweet fairground scent. Don, who has some of the lassitude you often find in very lanky people, seemed slightly horrified at just how big the beam was.

“

This

is what you call a ridge pole? I was picturing something a bit more bamboolike.”

“We call it a ridge pole to make it feel lighter,” Joe said. “But it’s really a big tree with the bark taken off and a few corners added.”

As the three of us shouldered the ridge pole from the barn out to the site, I thought back to the arrival of the corner posts on a winter morning six months before. Everything about this day seemed infinitely superior: the soft July air, the auspiciousness of the occasion, and the convenient fact that, this time around, mine was not the tallest shoulder underneath this massive tree. Don complained all the way out to the site.

Joe had stationed himself midway between Don and me, but as we neared the site he slipped out from under the beam (since he’s five-four, our burden scarcely changed) and trotted out ahead, climbing up into the frame to receive the ridge pole from us. Don, straining, pressed his end up over his head barbell-style while Joe guided it to a spot on the wall plate; then I did the same with my end. Working now nine feet off the ground, we drilled holes at each end of the ridge beam at the spot where it would set down onto the dowels we’d already mounted on the supporting king posts in our gable assemblies. Joe then directed the two of us in a new choreography of lumber that had Don and I manning opposite gables while he flew back and forth across the frame, helping us each in turn to hoist and then align our beam ends over their intended dowels. Don’s end went down first, sinking comfortably into its wooden pocket; I watched his tensed expression suddenly bloom into relief, mixed with a satisfaction he hadn’t been prepared for. My end took some manhandling, first to align the hole above the dowel, and then to force the beam all the way down into its slot, where it didn’t seem to want to go.

“Time for some physical violence,” Joe advised, and he handed his big framing hammer up to me. Now I pounded mightily on the top of the ridge beam—holding the hammer correctly, I might add—and inch by inch it creaked its way down onto the dowel, the tight-binding wood screeching furiously under the blows, until at last the beam came to rest on its king post, snug and immovable. That was it: the ridge pole set, our frame was topped out.

I asked Joe to hand me his big carpenter’s level; along with the tool he gave me a look that said, You’re really asking for it, aren’t you? There was nothing we could do, after all, if we discovered that our ridge beam was not true. I laid the level along the spine of the building as close to its midpoint as I could reach. From where he stood Joe had the better view into the level’s little window, and I read the excellent news in his face. “It doesn’t get any better,” Joe said, reaching out his hand for a slap. None of us wanted to come down from the frame, so we stood up there in the trees for a long time, beaming dumbly at one another, weary and relieved, savoring the sweetness of the moment.

In Colonial days the topping out of a frame was traditionally followed by a ceremony, and though the particulars varied from place to place and over time, certain elements turn up in most accounts. According to historian John Stilgoe, as soon as the ridge beam was set into place, the weary carpenters would begin pounding on the frame, “calling for wood.” Answering the call, the master builder would go off into the woods to cut down a young conifer and carry it back to the assembled helpers. As the tree sacrifice suggests, the flavor of these events was strongly pagan, even in Puritan America, though there was an effort in many places to work in a few Christian elements, such as the Lord’s Prayer. Often there would be some kind of test of divination: in one, the master builder would drive an iron spike into an oak beam, and if the wood didn’t split or bleed (being oak, it hardly ever did), the long life of both frame and owner was assured. Toasts and prayers followed, and then a bottle would be broken over the frame in a kind of christening. Many frames were actually given names; “the Flower of the Plain” was one I especially liked. After a toast to the workers and their creation, writes Stilgoe, “The harmony of builders, frame, and nature was assured, and the men raised the decorated conifer to the highest beam in the structure and temporarily fixed it. Thereafter the frame had the life of a living tree.”

“Keep all lightning and storms distant from this house,” went one common prayer, “keep it green and blossoming for all posterity.”

The only part of the traditional topping-out ceremony that has come down to us more or less intact is the nailing of the evergreen to the topmost beam. Even on a balloon-frame split-level in the suburbs, you’ll often see an evergreen bough tacked to the gable or ridge board before the vinyl siding goes on. I’ve seen steelworkers raising whole spruce trees to the top of a skyscraper frame high above midtown Manhattan. Perhaps it’s nothing more than superstition, men in a dangerous line of work playing it safe. Or maybe there’s some residual power left in the old pagan ritual.

I’ve read many explanations for the evergreen hanging, and all of them are spiritual in one degree or another. The conifer is thought to imbue the frame with the tree spirit, or it’s meant to sanctify the home, or to appease the gods for the taking of the trees that went into the frame. These interpretations sound reasonable enough, and yet they don’t account for the fact that someone as unsuperstitious and spiritually backward as me felt compelled to go out into the woods in search of an evergreen after we’d raised the ridge pole. Joe probably would have done it if I hadn’t, but it was my building, and there was something viscerally appealing about the whole idea, the way it promised to lend a certain symmetry to the whole framing experience, tree to timber to tree, bringing it full circle. But now that I’ve performed the ritual, I’m inclined to think there may be more to it than that. Like many rituals involving a sacrifice, there’s a kind of emotional wrench in the middle of this one. The hanging of the conifer manages all at once to celebrate a joyful rite—the achievement of the frame and the inauguration of a new dwelling—and to force a recognition that there is something slightly shameful in the very same deed.

People have traditionally turned to ritual to help them frame and acknowledge and ultimately even find joy in just such a paradox of being human—in the fact that so much of what we desire for our happiness and need for our survival comes at a heavy cost. We kill to eat, we cut down trees to build our homes, we exploit other people and the earth. Sacrifice—of nature, of the interests of others, even of our earlier selves—appears to be an inescapable part of our condition, the unavoidable price of all our achievements. A successful ritual is one that addresses both aspects of our predicament, recalling us to the shamefulness of our deeds at the same time it celebrates what the poet Frederick Turner calls “the beauty we have paid for with our shame.” Without the double awareness pricked by such rituals, people are liable to find themselves either plundering the earth without restraint or descending into self-loathing and misanthropy. Perhaps it’s not surprising that most of us today bring one of those attitudes or the other to our conduct in nature. For who can hold in his head at the same time a feeling of shame at the cutting down of a great oak, and a sense of pride at the achievement of a good building? It doesn’t seem possible.

And yet right here may lie the deeper purpose of the topping-out ceremony: to cultivate that impossible dual vision, to help foster what amounts to a tragic sense of what we do in nature. This is something that I suspect the people who used to christen frames understood better than we do. To build, their rituals imply, is in some way to alienate ourselves from the natural order, for good and bad. The cutting down of trees was an important part of it. But even before that came the need for a shelter in the first place—something that Adam had no need for in paradise. Like the clothes Adam and Eve were driven by shame to put on, the house is an indelible mark of our humanity, of our difference from both the animals and the angels. It is a mark of our weakness and power both, for along with the fallibility implied in the need to build a shelter, there is at the same time the audacity of it all—reaching up into the sky, altering the face of the land. After Babel, building risked giving offense to God, for it was a usurpation of His creative powers, an act of hubris. That, but this too:

Look at what our hands have made!

I don’t think it is an accident that the ceremonies came at the point they did in the building process, since it is the setting of the ridge beam that completes the shape of this symbol of our humanity: the gable crowning the square, the very idea of

house

written out in big timbers for all the world to see. The topping-out rituals performed by the early builders, with their peculiar mix of solemnity and celebration, must have offered them a way to reconcile the simultaneous shame and nobility of this great and dangerous accomplishment.

I’m more than a little embarrassed to utter any such words in connection with my own endeavor, so distant from my world do they sound. But along with the remnants of the old rituals, might there also be at least some residue of the old emotions? I remember, on that January morning when I took delivery of my fir timbers, how the sight of those fallen, forlorn timbers on the floor of my barn had unnerved me—“abashed” was the word I’d used. In the battle between the loggers and the northern spotted owl, I’d always counted myself firmly on the side of the owls. But now that I wanted to build, here I was, quite prepared to sacrifice not only a couple of venerable fir trees in Oregon, but a political conviction as well. I was also prepared to make a permanent mark on the land.

So maybe it was shame as much as exultation that brought me down off the frame that early summer evening, sent me out into the woods in quest of an evergreen to kill. Joe had forgotten which you were supposed to use, pine or hemlock or spruce. I decided any conifer would do. It was spruce I came upon first, and after I cut the little tree down and turned to start back to the site, holding the doomed sapling before me like a flag, I saw something I hadn’t really seen before: the shape of my building in the landscape. The simple, classical arrangement of posts and beams, their unweathered grain glowing in the last of the day’s light, stood in sharp relief against the general leafiness, like some sort of geometrical proof, chalked on a blackboard of forest. I stopped for a moment to admire it, and I filled with pride. The proof, of course, was of us: of the powers—of mind, of body, of civilization—that could achieve such a transubstantiation of trees.

Look at this thing we’ve made!

And yet nothing happens without the gift of the firs, those green spires sinking slowly to earth in an Oregon forest, and it was this that the spruce recalled me to. Joe had left a ladder leaning against the front gable. I climbed back up into the canopy of leaves, the sapling tucked under my arm, and when I got to the top I drove a nail through its slender trunk and fixed it to the ridge beam, thinking:

Trees!

6

The Roof

Building a roof is by its very nature conducive to speculation, if only because one spends so much of the day so high up in the trees, taking in the big picture. In fact, the process of shingling a roof in wood is the sort of repetitive operation that actually benefits from a certain distractedness on the part of the shingler. Focus too closely on the work at hand and your shingles are apt to fall into a rigid, mechanical pattern, when it’s a more organic regularity, something just this side of casual, that you’re looking for. This I managed to achieve (shingling obviously played to my strength, such as it is), and perhaps the following reflections on roofs, and other elevated matters, deserve part of the credit.

To think about roofs is to think about architecture at its most fundamental. From the beginning, “the roof” has been architecture’s great synecdoche; to have “a roof over one’s head” has been to have a home. The climax of every primitive but narrative I’ve read arrives with the invention of the roof, the big moment when the tree limbs are angled against one another to form a gable, and then covered with thatch or mud to shut out the rain and the heat of the sun. If the first purpose of architecture is to offer a shelter against the elements, it then stands to reason that the roof is in some sense its primary creation. It’s the place where the dreams of architecture meet the facts of nature.

The roof also seems to be the place where, in this century, architecture and nature parted company, where the ancient idea that there are rules for the art of building that are given with the world—an idea first expressed by Vitruvius, and embodied in the myth of the primitive hut—went, well, out the window. At first the notorious leaking roofs of contemporary architecture seemed too cheap and obvious a metaphor for this development. But my time up in the rafters roofing and dwelling on roofs eventually got me to thinking that the leaky roof, taken seriously, might in fact have something to tell us about the architecture of our time.

But before I could think too hard about roofs as metaphor, I needed to learn something about them as structure, if I hoped to get mine framed and shingled and weather-tight that summer before the cold weather returned. Frank Lloyd Wright, who made much of roofs in his work (and who designed more than his share of leaky ones), wrote in his account of mankind’s earliest builders that “The lid was troublesome to him then and has always been so to subsequent builders.” Roofs have always been the focus of a considerable amount of technological effort, since, as Wright noted, “more pains had to be taken with these spans than with anything else about the building.” We tend to forget that, for much of its history, architecture stood at the leading edge of technology, not unlike semiconductors or gene splicing today. The architect saw himself less as an artist than a scientist or engineer, as he pushed to span ever-bigger spaces, to build higher and higher, and to realize such marvels of engineering as towers and domes. Historically, the roof has been the place where architecture confronted the challenge not only of the elements, but of nature’s laws.

*

Perhaps this accounts for a certain anxiety that seems to hover over a roof, even one as seemingly straightforward as mine. It had never occurred to either Joe or me that our simple forty-five-degree gable roof was in any way pushing the technological envelope, but, unbeknownst to us, Charlie had been sufficiently concerned about its structural integrity to have an engineer look over his design and run a few calculations.

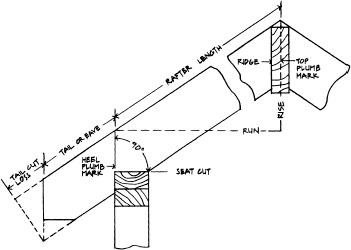

The July afternoon Joe and I first heard about the engineer—Charlie having accepted Joe’s dare-you invitation to help us cut and nail rafters—the architect came in for a lot of kidding. The day was very much Joe’s. Cutting rafters is a complicated and unforgiving procedure, and Joe had shown up on time and armed with a detailed sketch indicating the precise location and angle of each of the four cuts each rafter needed: the ridge and tail cuts at each end—parallel to one another at a forty-five-degree angle to the rafter’s edge—and the heel and seat cuts that form the “bird’s mouth” where the rafter engages the top of the wall—a rectangular notch that in our case had to have a slightly different depth, or heel cut, on each rafter to account for the fact that our two side walls were not precisely parallel.

Joe had clearly done his homework, could even spout the formula for determining the length of a rafter: , in which the rise is the height of the gable and the run is the horizontal distance covered by each rafter, or one half the width of the building. For his part, Charlie was feeling somewhat deflated after a punishing meeting with a client, and seemed in no shape to mix it up with a cocky carpenter who’d come equipped with enough geometry to frame a roof single-handed and who didn’t see much point in architects to begin with.

, in which the rise is the height of the gable and the run is the horizontal distance covered by each rafter, or one half the width of the building. For his part, Charlie was feeling somewhat deflated after a punishing meeting with a client, and seemed in no shape to mix it up with a cocky carpenter who’d come equipped with enough geometry to frame a roof single-handed and who didn’t see much point in architects to begin with.

“Charlie, just explain this to me,” Joe began, gesturing with his big carpenter’s square. “The building is only eight feet by thirteen, correct? It gets a roof that’s framed with four-by-eight rafters and a ridge beam ten inches thick.

Plus

you’re calling for two collar ties and a pair of king posts, all of which you want us to dowel together. So tell me: How can we

possibly

have anything to worry about structurally? This building’s been designed for a

three-

hundred-year storm!”

Charlie managed a wan smile. He explained, somewhat sheepishly, that he’d needed to check with the engineer on the dimensions and spacing of the straps—the strips of wooden lath that run perpendicularly across the rafters to give us something to nail our shingles to. The fact that our rafters are a full thirty inches apart meant the lath would have to span an unusually great distance. Charlie had wanted to know the minimum dimensions he could safely spec these pieces, since the underside of the roof was to be entirely exposed. If the straps were too heavy, they’d wreck the delicate, rhythmic effect he was aiming for in the ceiling, which he’d told me was going to look something like the inside of a basket or the hull of a wooden boat. Yet if the lath were too light, it was liable to deflect, or bend, under stress.

While Charlie was working with the engineer to determine the dimension of the straps, he figured it couldn’t hurt to have him run the rest of the calculations on the roof. Charlie explained that any time you have an open, “cathedral” ceiling with no attic, there are special structural problems to solve. As gravity exerts a downward pressure on a roof, the rafters in turn want to push the walls outward, a force that in a traditional structure is countered by the ceiling joists, which tie each pair of rafters together at the bottom, joining them in a taut triangle. But when the living space reaches directly up under the roof, these joists are eliminated, so either the walls have to be sturdy enough to withstand the outward thrust of the rafters or an occasional cross-tie beam must be provided to counteract it. It was Frank Lloyd Wright who pioneered such a ceiling, and it may well have been the novel structural and insulating problems it raised that caused some of his roofs to leak. Following Wright’s example, Charlie wanted to give the interior of my building a pronounced sense of “roofness,” one of those instances in architecture where expressing a structure seems, ironically, to complicate its construction.

“Anyway, you’ll be happy to hear we’ve got nothing to worry about—the two cross-ties take care of our lateral stresses, and the king posts cut the weight carried by the ridge pole almost in half. And as far as those dowels are concerned, don’t forget that in a storm you have upward forces working on a roof, too.”

Joe and I both laughed; nothing about my building seemed in danger of blowing away. A few weeks before, as the frame was taking shape, I’d remarked to Charlie about how very heavy it looked. “But it’s not meant to be light,” Charlie had protested. “This is your study, your library—it’s an institution!” When I passed that one on to Joe, a look of concern swept over his face: “Mike, don’t you think there’s

another

kind of institution we should be talking to Charlie about?”

But there was nothing funny about the issue as far as Charlie was concerned. Charlie’s nightmares, I knew, featured collapsing roofs and deflecting cantilevers. No doubt the fact that this particular design was being built by a crew consisting 50 percent of me made him even more nervous than usual. Out of the blue, Charlie would phone to reassure himself I was using galvanized nails in the frame; he’d heard about a house on Cape Cod that had simply crumpled to the ground one day, the salt air having rusted its common nails to dust. No doubt such worries disturb the sleep of all architects to one degree or another. When the massive concrete cantilevers of Fallingwater were being poured, Frank Lloyd Wright, delirious with fever at the time, was heard to mumble, “Too heavy! Too heavy!”

*

“You two can laugh,” Charlie said, “but I’m the one who’s ultimately responsible, and it makes me sleep better knowing that an engineer has run all the calculations.” He launched into a story he’d already told me twice before, about an opening-day bridge collapse in Tacoma. Joe chimed in with a few horror stories of his own, the sort of thing I imagine you could get your fill of in the bar at a convention of structural engineers, and by the time he got around to a fatal hotel atrium collapse in Kansas City, we were all feeling pretty good about our roof, about just how beefy it was going to be. While we talked, the three of us were lifting the chunky rafters into place, lining them up over the fin walls as best we could (our frame being, in Joe’s cheerful new formulation, “too hip to be square”) and then toe-nailing them to the ridge beam above and wall plate below with (galvanized) twelve-penny nails almost as fat as pencils. We had all eight rafters securely in place before Charlie had to drive back to Cambridge, and the completed roof frame looked for all the world like a gigantic rib cage, its great fir bones wrapping themselves around a sheltered heart of space. Add to this skeleton a skin of cedar shingles, and you had the very kind of place where a body wouldn’t mind riding out the storm of the century.

It seems difficult if not impossible to avoid figurative language when talking about roofs, they’re so evocative, so much more than the sum of their timbers and shingles and nails. To creatures who depend on them for their survival, it is perhaps inevitable that roofs are symbols of shelter as well as shelters themselves. Seen from afar or in a painting or movie, roofs also symbolize

us—

our presence in a landscape. Of course people have attached innumerable other meanings to roofs as well, and many of these meanings have changed over time. The traditional gable, for example, meant something very different after modernism than it did before.

Many of the important battles over style in architectural history can be seen as battles over roof types: the Gothic arch versus the classical pediment, the Greek Revival gable versus the Colonial saltbox, the international style flattop versus all of history’s pitched roofs. In this century, the pitched roof became the most hotly contested symbol in all of architecture. Nothing did more to define modernist architecture than its adoption of the flat roof—and nothing did more to define postmodernism than its resurrection of the gable. Since then, architecture’s avant-garde has sought to explode the very idea of a stable, dependable roof, violently “deconstructing” both the gable and the flattop. But the twentieth-century argument about roofs turns out to be about a lot more than that: it’s really an argument about the very nature of architectural meaning, which seems to have undergone a thorough transformation in the last few years. I’ve come to think this transformation holds a clue to the disappearance of the old idea that architecture was somehow grounded in nature, as well as to the subsequent rise of the kind of literary architecture I had found in the pages of

Progressive Architecture

. You can get a good view of these developments up on the roof.

“Starting from zero” was the rallying cry of modern architecture, and for the roof that meant banishing the gable, which the modern movement took as a key symbol of the architectural past—of everything musty and old and sentimental. Arguably the pitched roof (of which the gable is the most basic form) is architecture’s first and most important convention—wasn’t that the point of all those primitive-hut tales?—and under the modernist dispensation all conventions were to be tested against the standard of pure rationalism and function. The demonstrable fact that the pitched roof is

supremely

functional suggests that modernist rationalism sometimes took a backseat to modernist iconoclasm.