A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (37 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

The two most important voices in a progression are the top and bottom voices. This is because they're the easiest for the ear to pick out. If you're playing a chording instrument, other instruments may be playing the actual melody and bass line, but for purposes of looking at the chord part itself, we can talk about the top voice as the melody and the bottom voice as the bass line.

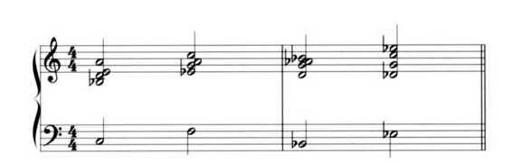

When two voices both move up or down at the same time, and both move by the same interval, we say that they're moving in parallel motion, as in the example of parallel 5ths given above. If they both move in the same direction but move by different intervals, they're engaging in similar motion. If one voice moves up while the other moves down, they're moving in contrary motion. Parallel and similar motion between the melody and bass line tends to give the chord part a solid, somewhat rigid quality, as Figure 8-25 shows. It's especially noticeable when the melody and bass line move by the same interval.

Figure 8-24. A two-bar progression, voiced first with smooth voice leading and then with radically disjunct voice leading.

If all of the voices of the chords move up or down by the same interval, as in the first measure of Figure 8-25, essentially the entire chord is moving up or down as a block. This is occasionally a good strategy when you want to make an emphatic statement, but connecting more than two or three chords in a row by means of rigid parallel motion will give your music a dull, stiff character. It shows a lack of imagination. Introducing some contrary motion where appropriate will give the music a more supple sense of movement. Contrary motion between the top and bottom voices tends to sound good, because it emphasizes their identities as independent lines.

When a voice moves by leap rather than by step, it's usual for the note following the leap to fall back toward the starting point, as shown in Figure 8-26. The larger the leap, the more desirable it is for the melody to move back in the other direction as a stabilizing force. Here again, however, the "rule" is anything but absolute. The original melody in Figure 8-27, in which upward leaps of a 5th are followed by another upward-moving interval, sounds perfectly natural.

Figure 8-25. In bar 1, all of the voices move in parallel motion: The chord moves as a block. In bar 2, there is some contrary motion in the inner voices, but the bass line and melody continue to move in parallel. Between bars 1 and Z the top and bottom voices move in similar motion (the same direction, but by different intervals).

Figure 8-26. When a voice uses disjunct motion, it's normal for the next note following the leap to fall back toward the starting point.

Figure 8-27. While the treatment of disjunct motion shown in Figure 8-26 is the norm, violating the norm is not unheard of. This original melody, which begins with the same notes as "Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered, " shows another way of treating leaps. As in the melody of "Bewitched, " the repeated violation of the norm creates a sort of gravitational pull, which more or less demands that the final leap be followed by a more extended fall (in this case, the E-D-C-B-A at the end) back toward the starting point.

Another important aspect of voice leading is where you start and where you end up. Generally speaking, moving upward conveys a sense of increasing intensity. This is especially true with respect to melodic movement: The emotional peak of a phrase is often the point at which the highest melody notes are played or sung. If all of the voices of a chord are high, a feeling of great excitement can be generated.

Moving the bass line upward doesn't have quite so clear-cut an effect. This is because the music will sound more full and have a greater impact when the bass part is lower rather than higher. If the melody and bass move in contrary motion, the bass will reach its lowest point as the melody reaches its highest point. This can be a moment of great power. An unusually high bass part can also produce an intense effect, however. You may find it useful to play with this factor in your own arrangements.

Chordal parts seem to sound best when most of the chords use about the same number of voices. To see why, try playing the music in Figure 8-28. The first riff in this figure sounds balanced and logical, not only because of the smooth voice lead ing (only one of the upper voices moves, and then by half-step) but because the right-hand voicings in the two chords have the same number of voices. By comparison, the second riff sounds more than a bit odd. It's almost as if we're hearing two chording instruments, one of which is being cut out by an intermittent electrical problem. Again, this is not necessarily a bad effect. Moving unexpectedly from a thick chord voicing to a thin one or vice-versa can add real emotional depth. But if you do it routinely and casually, your music will have a disjointed quality that your listeners will have to struggle with.

Figure 8-28. It's generally a good idea to use about the same number of voices in each chord. The first riff here utilizes three-voice chords in the right hand. The second riff is very similar, except that the right hand switches between five-voice chords and two-voice chords.

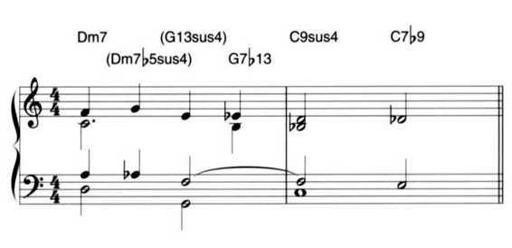

Because voices outline chords, it's sometimes open to debate whether passing tones in one or two voices should be analyzed as producing an entirely new chord, or whether momentary harmonies produced by passing tones should be ignored in an analysis of the progression. Figure 8-29 provides an illustration of this. The underlying progression in measure 1 is clearly from a Dm7 to a G7613. The two chords in the middle of the measure are produced by the motion of what classical theorists would call the soprano and tenor voices. The fact that there's no root movement between the two D chords, and again none between the two G chords, lends weight to the idea that the two chords in the middle of the measure aren't quite real. The voice leading through passing tones in Figure 8-30 is similar, but here I would tend to analyze each chord as being an independent part of the progression, because the roots are moving.

Figure 8-29. The movement of individual voices sometimes creates temporary harmonies. The basic chord progression in measure I here is between the Dm7 and the G7613; the two chords in the middle of the measure are less significant. Note that as a chromatic passing tone, the At, is moving toward G. Because this is a four-voice texture, however, doubling the root of the G chord wouldn't leave enough voices to provide harmonic color. The G in the upper voice is an incomplete neighboring tone - that is, the underlying movement of this voice is from F to G and back to F. If the second F were played, the G would be an ordinary (complete) neighboring tone. The parallel major 7th adds interest to the voice leading.

Figure 8-30. As in Figure 8-29, passing harmonies are created in this progression by smooth movement of the voices. The underlying progression is G7-C13-Fadd9. Because the passing chords have their own roots, however, they'll be more readily heard as independent parts of the progression. Note that the At, in measure 1 and the BI; in measure 2 violate the principles of enharmonic spelling discussed in Chapter Seven. The spellings shown are preferable, however, because they make the chords easier to read.

GERMAN & NEAPOLITAN 6THS

If you listen to classical music written between 1780 and 1880, you'll often hear a few non-diatonic chords that add to the palette of chord progressions: the family of augmented 6th chords and the Neapolitan 6th. None of these is a 6th chord in the sense in which jazz musicians use the term; the reasons why they're called 6th chords will become clear as we proceed.