A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (7 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

A system in which the black keys on the keyboard can be referred to with the letter-name of either the white key below them (as a sharp) or the white key above them (as a flat) gives us a clear, concise way to notate and talk about all of the scales, chords, and intervals that are commonly used.

Figure 1-15. Enharmonic equivalents. Each pair of notes shown here produces the same pitch. Notes like E# and C', are not often needed; they're only used in keys that already have lots of sharps or flats in the key signature.

The F# and G6 scales illustrate another concept that will be useful from time to time. While a sharp or flat note is normally one of the black keys on the keyboard, this is not always the case. Remember that making a note sharp simply means raising it by a half-step. When we raise the note E or B by a half-step to E# or B#, we land on another white key (F or C respectively). So E# and F are enharmonic equivalents. The same thing is true of B# and C, F6 and E, and C6 and B (see Figure 1-15).

QUIZ *

1. What are the four basic elements of music?

2. Which major key has four sharps in the key signature? Which major key has two flats?

3. What is the relationship between two pitches called?

4. What is a set of three or more notes played together called?

5. What is the enharmonic equivalent of A6? Of D6? Of C?

6. What is a unison?

7. What instrument is the arpeggio named for?

8. When two notes are almost in tune, but not quite, playing them together produces a clash. What is the technical term for the sound of this clash?

INTERVALS

n order to work with chords and harmony, you have to start by developing a clear understanding of intervals. Intervals are the building blocks out of which all of the more complex phenomena of harmony are built. An interval, as explained in Chapter One, is simply a relationship between two notes.

n order to work with chords and harmony, you have to start by developing a clear understanding of intervals. Intervals are the building blocks out of which all of the more complex phenomena of harmony are built. An interval, as explained in Chapter One, is simply a relationship between two notes.

Technically, an intervallic relationship is between pitches, not notes. A note is a musical entity that has a pitch and also a duration. For instance, it might be an eighth-note with a pitch of E6. Notes, even if they're written on paper and never heard, are intended to be played, while pitches are abstractions. Most notes also have definite rhythmic positions within a piece of music, though of course it's possible to play one note in isolation. In this book, however, I'll generally use the more comfortable, familiar term. I'll refer to the elements of intervals and chords most often as notes, not as pitches.

We've already met several intervals in Chapter One: the unison, the octave, the 5th, the major 3rd, the half-step, and the whole-step. The time has come to define these terms in a more systematic way.

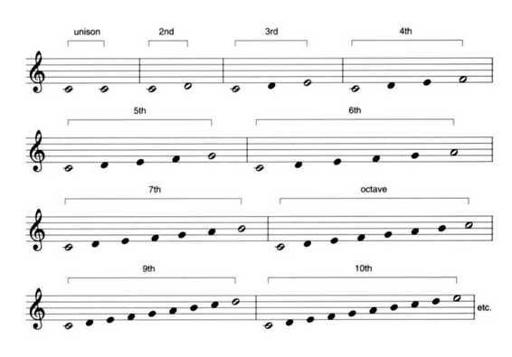

Figuring out the name of an interval is pretty easy: You do it by counting the number of scale steps between the lower and upper notes (including both of the notes in the count). This idea is shown in Figure 2-1.

The unison and octave could just as easily be called the 1st and 8th, but their special importance is highlighted by giving them special names. The two notes of a unison are the same. The two notes of an octave both have the same name (C and C, in Figure 2-1), and in many harmonic contexts are interchangeable, but they're not the same. If you're new to music, learning to hear the difference between two notes an octave apart may require a little effort, because they sound very similar.

Figure 2-1. The names of intervals are based on how many steps of the scale are included within the span of the two notes of the interval. Both the top and bottom notes of the interval are counted in figuring out the name. In this diagram the notes of the scale between the two notes of the interval are shown as black noteheads, while the notes of the interval are shown as hollow noteheads.

Before moving on, you need to notice several things about Figure 2-1 that may not be obvious at first glance.

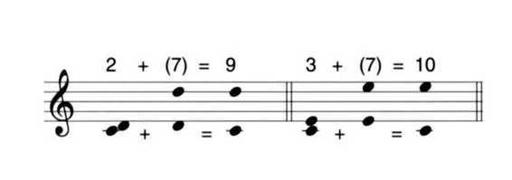

First, the interval of a 9th consists of two notes with the same note names (C and D) as the interval of a 2nd. Likewise, the 10th has the same note names as the 3rd. In essence, a 9th consists of a 2nd plus an octave, and a 10th consists of a 3rd plus an octave.

Since an octave spans eight notes, you might expect that when jumping up an octave you'd use the formula 2 + 8 = 10 to find the name of the wider interval. But it doesn't work that way. Since the octave note (the upper C in Figure 2-1) is only counted once, you add an octave to an interval by adding seven to its name. For a 2nd, the formula is 2 + 7 = 9. For a 3rd it's 3 + 7 = 10. This idea is illustrated in Figure 2-2.

Second, to save space Figure 2-1 doesn't include any intervals larger than a 10th, but such intervals exist. Musicians seldom have need to refer by name to intervals larger than a 13th. With a very large interval, you'd be more likely to say something like, "Two octaves plus a 5th"

Figure 2-2. To increase an interval by an octave, add 7 (not 8) to the name. A 2nd plus an octave equals a 9th; a 3rd plus an octave equals a 10th.

Third, the name of the interval doesn't depend on the order of the two notes. For the sake of convenience and consistency, in this book we'll most often talk about intervals by stating the lower of the two notes first, but this is arbitrary. The interval from C up to G is the same as the interval from G down to C (but not the same as the interval from C down to G, as you'll soon learn).

Fourth, a C major scale has been used in Figure 2-1 purely for convenience, and the lower note of all the intervals is C. Many of the examples in this book will be given in the key of C, but all of the harmonic phenomena we'll be discussing can be transposed to any key. The intervals D-F, E-G, and so on are all 3rds, just as C-E is.

Finally, some important intervals seem to be missing from Figure 2-1. Where, for instance, is our good friend the half-step? Somewhere between the unison and the 2nd, it would seem. And what about the distance between C and A6? What are we to call it? A system that didn't provide names for all of the intervals wouldn't be very useful. So the question of what to call those "in-between" intervals is what we'll turn to next.

NARROWING & WIDENING THE INTERVALS

The concept I'm about to introduce may be hard to remember at first. It may seem arbitrary or nonsensical. In fact, it makes excellent sense, but for reasons that won't be fully explained until we get to Chapter Seven.

Within the major scale there are two kinds of steps. Some of the notes are called tonal steps and some are called modal steps. In each scale, the tonal steps are the tonic, the 4th, the 5th, and the octave (in the C scale, the notes C, F, G, and C). The other steps (the 2nd, 3rd, 6th, and 7th) are the modal steps. The same thing is true of steps in the second octave: The 9th and 10th are modal, the 11th and 12th tonal.

The reasoning behind these terms is that the modal steps change, depending on what mode you're using. (As explained in Chapter Seven, a mode is a type of scale.) The 3rd, for instance, will be lowered by a half-step when we change from a major scale to the minor scale that has the same tonic. The tonal steps remain fixed in most of the classical modes, though they're altered in some jazz scales.

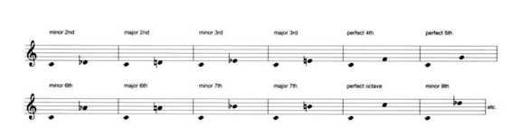

Modal steps have two basic forms, which are called major (which is Latin for "bigger") and minor (Latin for "smaller"). Tonal steps have only one basic form, which is called perfect (that's English for "don't ever change"). If we count the number of half-steps in an interval instead of the number of scale steps, we'll find that a minor interval always has one fewer half-steps than its major counterpart. A minor 2nd, for example, is one half-step in width, while a major 2nd is two halfsteps wide. These relationships are summarized in Figure 2-3 and Table 2-1.