A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (15 page)

Read A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide Online

Authors: Samantha Power

Tags: #International Security, #International Relations, #Social Science, #Holocaust, #Violence in Society, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #General, #United States, #Genocide, #Political Science, #History

Proxmire's speech-a-day approach to ratification was one of many rituals he observed in the Senate. He made a point (and a show) of never missing a roll call vote during his twenty-two years in the Senate, tallying more than 10,000 consecutively. A renowned skinflint, he became famous nationally for crusading against pork-barrel projects and passing out the monthly Golden Fleece Awards to government agencies for waste in spending. The first award in 1975 went to the National Science Foundation for funding a $84,000 study on "why people fall in love." Later recipients were "honored" for a $27,000 project to determine why initiates want to escape from prison; a $25,000 grant to learn why people cheat, lie, and act rudely on Virginia tennis courts; and a $500,000 grant to research why monkeys, rats, and humans clench their jaws. The award infuriated many of Proxmire's colleagues in the Senate, who deemed it a publicity stunt designed to earn Proxmire kudos at their expense."

Although Proxmire alienated some colleagues by "fleecing" them, a few joined him in fighting for the genocide convention. Claiborne Pell, a fellow Democrat from Rhode Island, was one who endorsed Proxmire's pursuit." Pell's father, Herbert C. Pell, had served during World War II as U.S. representative to the War Crimes Commission, which the Allies established in 1943 to investigate allegations of Nazi atrocities. The elder Pell had hardly been able to get senior officials in the Roosevelt administration to return his calls. In late 1944 he was informed that the war crimes office would close for budgetary reasons.The Roosevelt team rejected Pell's offer to pay his secretary and the office rent out of his own pocket, reversing the decision only when Pell publicized the office's closing. When the younger Pell spoke publicly on behalf of the genocide convention decades later, he recalled those years in which he watched his father come to terms with the outside world's disregard for Nazi brutality:

I remember the shock and horror that my father suffered-he was a gentle man-at becoming aware of the horror and heinousness of what was going on.... I am convinced ... that there was an unwritten gentleman's understanding to ignore the Jewish problem in Germany, and that we and the British would not intervene in any particular way.... We wrung our hands and did nothing."

Backed by Pell, Proxmire pressed ahead in an effort to resurrect Lemkin's law. Proxmire's daily ritual became as regular and predictable as the bang of the gavel and the morning prayer. Yet it was also as varied as the weather. Each speech had to be an original. The senator put his interns to good use, trusting them, in weekly rotations, to prepare the genocide remarks. The office developed files like Lemkin's on each of the major genocides of the past millennium, and the interns tapped the files each day for a new theme. Anniversaries helped. The Turkish genocide against the Armenians and the Holocaust were often invoked.

But sadly, Proxmire's best source of material was the morning paper. In 1968 Nigeria responded to Biafra's attempted secession by waging war against the Christian Ibo resistance and by cutting off food supplies to the civilian population. "Mr. President, the need of the starving is obvious. Indeed, it cries to high heaven for action," Proxmire declared. "And to the degree that the nations of the world allow themselves to be lulled by the claim that the elimination of hundreds of thousands of their fellows is an internal affair, to that degree will our moral courage be bankrupt and our humane concern for others a thin veneer. Our responsibility grows awesomely with the death of each innocent man, woman and child."" But the United States stood behind Nigerian unity. Reeling from huge losses in Vietnam as well as the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, the Johnson administration followed the lead of the State Department's Africa bureau and its British allies, both of which adamantly opposed Biafran secession. Citing fears of further Soviet incursions in Africa and eyeing potentially vast oil reserves in Iboland, U.S. officials stalled effective famine relief measures for much of the conflict.The United States insisted that food be delivered through Lagos, even though Nigerian commanders were open about their objectives. "Starvation is a legitimate weapon of war," one said.s" In the end Nigeria crushed the Ibo resistance and killed and starved to death more than 1 million people

Beginning in March 1971, after Bengali nationalists in East Pakistan's Awami League won an overall majority in the proposed national assembly and made modest appeals for autonomy, Pakistani troops killed between 1 and 2 million Bengalis and raped some 200,000 girls and women. The Nixon administration, which was hostile to India and using Pakistan as an intermediary to China, did not protest. The U.S. consul general in Dacca, Archer Blood, cabled Washington on April 6, 1971, soon after the massacres began, charging:

Our government has failed to denounce atrocities ... while at the same time bending over backwards to placate the West Pak[istan] dominated government.... We have chosen not to intervene, even morally, on the grounds that the Awanu conflict, in which unfortunately the overworked term genocide is applicable, is purely an internal matter of a sovereign state. Private Americans have expressed disgust. We, as professional civil servants, express our dissent.

The cable was signed by twenty U.S. diplomats in Bangladesh and nine South Asia hands back in the State Department."' "Thirty years separate the atrocities of Nazi Germany and the Asian sub-continent," Proxmire noted, "but the body counts are not so far apart.Those who felt that genocide was a crime of the past had a rude awakening during the Pakistani occupation of Bangladesh""'' Only the Indian army's invasion, combined with Bengali resistance, halted Pakistan's genocide and gave rise to the establishment of an independent Bangladesh. Archer Blood was recalled from his post.

In Burundi in the spring and summer of 1972, after a violent Hutu-led attempted coup, the ruling Tutsi minority hunted down and killed between 100,000 and 150,000 Hutu, mainly educated elites."' Although the rate of slaughter reached 1,000 per day and open trucks of corpses rolled past the U.S. embassy, ambassador Thomas Patrick Melady downplayed atrocities for fear the State Department would overreact and undermine the U.S. relationship with the regime. The United States was the world's main purchaser of the country's coffee, which accounted for 65 percent of Burundi's commercial revenue. Despite this leverage, the State Department opposed any suspension of commerce. "We'd be creamed by every country in Africa for butting into an African state's internal affairs," one foreign service officer said. "We just don't have an interest in Burundi that justifies taking that kind of flack""' Another State Department official met a junior official's appeal for action by asking, "Do you know of any official whose career has been advanced because he spoke out for human rights?""' Here Senator Proxmire criticized the Organization for African Unity for refusing to investigate. He noted that the genocide convention made clear that such a crime was not a matter merely of internal concern but a violation of international law that demanded international attention. "The United States has for too long blithely ignored the issues of genocide," Proxmire said. "Evidence that genocide is going on in the 1970s should shake our complacency.""'

Proxmire had no shortage of grim news pegs on which to hang his appeal. His staff drew upon a range of sources, but their creative juices sometimes dried up. Even the lugubrious Lemkin with his file folders on medieval slaughter would have struggled to devise a novel speech each day. One evening an enterprising intern in Proxmire's office was struggling to prepare the next morning's speech when a pest control team arrived to sanitize the senator's quarters. The next morning Proxmire rose on the Senate floor and heard himself declare that the late-night visit of exterminators to his office "reminds me, once again, Mr. President, of the importance of ratifying the Genocide Convention."As taxing as it sometimes was to diversify the ratification pitch, nobody on Proxmire's staff considered slipping an old speech into Proxmire's floor folder in the hopes he would not remember having seen it before. "Prox had a hawk-like memory, the sharpest mind I ever came across," says Proxmire's convention expert Larry Patton, "I never had the guts to try."

Proxmire used his daily soliloquy to rebut common American misperceptions that had persisted since Lemkin's day. Powerful right-wing isola tionist groups would never come around. But most Americans, the senator believed, did not really oppose ratification; they were just misinformed. "The true opponents to ratification in this case are not groups or individuals," Proxmire noted in one of 199 speeches he gave on the convention in 1967. "They are the most lethal pair of foes for human rights everywhere in the world-ignorance and indifference.""' He used the speeches to educate. As critics picked apart the treaty and highlighted its shortcomings, he responded," I do not dismiss this criticism or skepticism. But if the U.S. Senate waited for the perfect law without any flaw... the legislative record of any Congress would be a total blank. I am amazed that men who daily see that the enactment of any legislation is the art of the possible can captiously nit pick an international covenant on the outlawing of genocide..""

Proxmire believed the United States could be doing far more in the court of public opinion to impact state and individual behavior. "The United States is the greatest country in the world," he said. "The pressures of the greatest country in the world could make a potential wrongdoer think before committing genocide .1117 But the United States neither ratified the UN genocide convention nor denounced regimes committing genocide. U.S. military intervention was not even considered.

Initially, Proxmire thought it might take a year or two at most to secure passage. "I couldn't think of a more outrageous crime than genocide," he recalls. "Of all the laws pending before Congress, this seemed a no-brainer" On the floor he listed other treaties that the Senate had endorsed in the period it had allowed the convention to languish:

Included among the hundred-plus treaties are a Tuna Convention with Costa Rica, a bridge across the Rainy River, a Halibut Convention with Canada, a Road Traffic Convention allowing licensed American drivers to drive on European highways, a Shrimp Convention with Cuba ... a treaty of amity with Muscat and Oman, and even a most colorful and appetizing treaty entitled the "Pink Salmon Protocol." I do not mean to suggest that any of these treaties should not have been ratified.... But every one ... has as its objective the promotion of either profit or pleasure.""

The genocide convention, by contrast, dealt with people. Because it did not promote profit or pleasure for Americans, it did not easily garner active support. Opponents of the treaty were more numerous, more vocal, and in the end more successful than Proxmire could have dreamed. Undeterred by failure, Proxmire would continue his campaign into the next decade. Indeed, nineteen years and 3,211 speeches after casually pledging in 1967 to speak daily, Proxmire would still be rising in an empty Senate chamber, dressed in his trademark tweed blazers and his Ivy League ties, insisting that ratification would advance America's interests and its most cherished values.

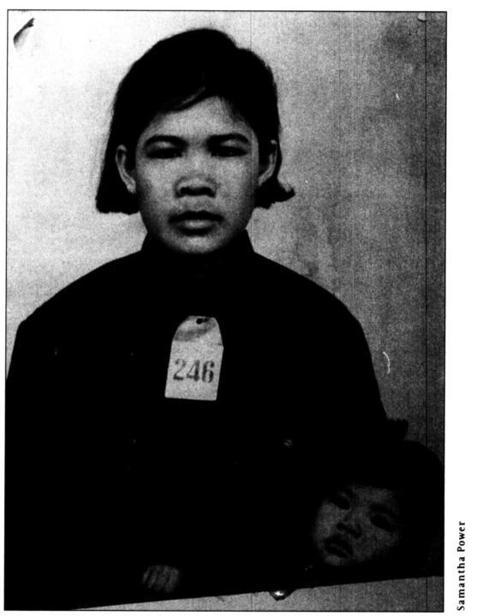

Photo of a Cambodian woman and her child, taken at the Tool Sleng torture center, shortly before they were murdered.

Chapter 6

Cambodia:

"Helpless Giant"

On April 17, 1975, eight years after Proxmire began his campaign to get the United States to commit itself to prevent genocide, the Khmer Rouge (KR) turned back Cambodian clocks to year zero. After a five-year civil war, the radical Communist revolutionaries entered the capital city of Phnom Penh, triumphant. They had just defeated the U.S.-backed Lon Nol government.

Still hoping for a "peaceful transition," the defeated government wel- corned the Communist rebels by ordering the placement of white flags and banners on every building in the city. But it did not take long for all in the capital to gather that the Khmer Rouge had not come to talk. After several days of monotonous military music interspersed with such tunes as "Marching Through Georgia" and "Old Folks at Home," the old regime delivered its last broadcast at noontime on the 17th.' The government announcer said talks between the two sides had begun, but before he could finish, a KR official in the booth harshly interrupted him: "We enter Phnom Penh not for negotiation, but as conquerors .112

The sullen conquerors, dressed in their trademark black uniforms, with their red-and-white-checkered scarves and their Ho Chi Minh sandals cut out of old rubber tires, marched single file into the Cambodian capital. The soldiers had the look of a weary band that had fought a savage battle for control of the country and its people. They carried guns. They gathered material goods, like television sets, refriger ators, and cars, and piled them on top of one another in the center of the street to create a pyre. Influenced by the thinking of Mao Zedong, the Khmer Rouge leadership had recruited into their army those they deemed, in Mao's words, "poor and blank," rather than those with schooling. "A sheet of blank paper carries no burden," Mao had noted, "and the most beautiful characters can be written on it, the most beautiful pictures painted."