A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (41 page)

Read A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide Online

Authors: Samantha Power

Tags: #International Security, #International Relations, #Social Science, #Holocaust, #Violence in Society, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #General, #United States, #Genocide, #Political Science, #History

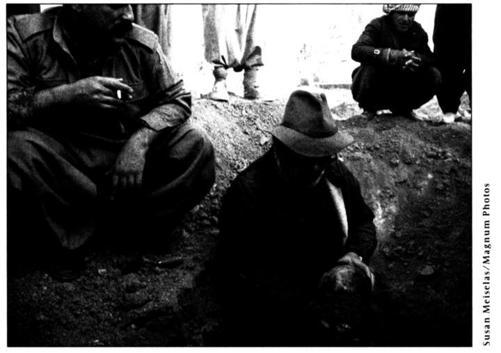

Human Rights Watch dispatched its researchers to Iraqi Kurdistan in 1992 and 1993, where they interviewed some 350 survivors and witnesses to the slaughter. The organization exhumed mass graves and gathered forensic material, such as traces of chemical weapons found in soil samples and bomb shrapnel, as well as the skeletons of the victims themselves. Excavators found rope still tying the hands of the decomposed men, women, and children. One foray yielded a fully preserved woman's braid.""

The eighteen-month investigation by Human Rights Watch into Iraqi atrocities was the most ambitious ever carried out by a nongovernmental organization. It was the kind of study that a U.S. government determined to stop atrocities might well have attempted while the crimes were under way. The human rights group legitimated the earlier estimate of Shorsh Resool, the amateur investigator into the operation. The group found that between 50,000 and 100,000 Kurds (many of whom were women and children and nearly all of whom were noncombatants) were executed or disappeared between February and September 1988 alone. Hundreds of thousands of Kurds were forcibly displaced.The numbers of those eliminated or "lost" cannot be confirmed because most of the men who were taken away were executed by firing squad and buried in unexhumed, shallow mass graves in southwest Iraq, near the border with Saudi Arabia. The Kurdish leadership claims 182,000 were eliminated in the Anfal campaign. Mahmoud `Uthman, the leader of the Socialist Party of Kurdistan, tells of a 1991 meeting at which the Anfal's commander, al-Majid, grew enraged over this number. "What is this exaggerated figure of 182,000?" he snapped. "It couldn't have been more than 100,000..""'

Dr. Clyde Snow, forensic anthropologist, exhumes the blindfolded skull of a Kurdish teenager from a mass grave in Erbil, northern Iraq, December 1991.

For the first time in its history, Human Rights Watch found that a country had committed genocide. Often a large number of victims is required to help show an intent to destroy a group. But in the Iraqi case the confiscated government records explicitly recorded Iraqi aims to wipe out rural Kurdish life.

Having documented the genocide, Human Rights Watch assigned lawyer Richard Dicker to draw up a legal case in the spring of 1994. He hoped to get Canada, the Netherlands, or a Scandinavian state to enforce the genocide convention by at least filing genocide charges before the International Court of Justice. "My role was to make it happen by preparing a tight case and persuading a state to take it on," Dicker remembers. "Of course I failed spectacularly." Diplomats initially argued that Iraq had not committed genocide. "They would say, `Gee, this doesn't look like the Holocaust to me!"' Dicker recalls. But once they became familiar with the law, most officials dropped that objection and worried out loud about the consequences of scrutinizing a fellow state in an international court.

If a genocide case were filed at the ICJ, the court could recommend that Iraqi assets be seized or that Iraqi perpetrators be punished at home, abroad, or in some international court. International criminal punishment had not been levied since Nuremberg, but human rights lawyers hoped that the Iraq case would renew interest in prosecution. After several years of badgering by Dicker and colleague Joost Hiltermann, two governments confidentially accepted the challenge, but they refused to file the case unless a European state would join them.To this day no European power has agreed.

The U.S. Senate had ratified the genocide convention, but Dicker and others believed that the United States should keep a "low profile" on any ICJ genocide case against Iraq because of its nettlesome reservations to the treaty. Advocates feared that Hussein might use the American reservations to deny the ICJ jurisdiction."" Although HRW did not request American participation in the case, it did hope the United States would support the effort. After initially opposing the campaign, the State Department legal adviser received innumerable legal briefs and evidentiary memos from Human Rights Watch, and changed his mind. In July 1995 Secretary of State Warren Christopher signed a communique that found Iraq had committed genocide against Iraq's rural Kurds and that endorsed HRW's efforts to file a case against Iraq.

To this day, however, no Iraqi soldier or political leader has been punished for atrocities committed against the Kurds.

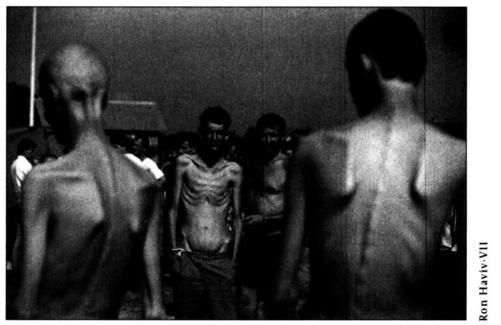

Muslim and Croat prisoners in the Serb concentration camp of Trnopolje.

Chapter 9

Bosnia: "No More

than Witnesses at

a Funeral"

"Ethnic Cleansing"

If the Gulf War posed the first test for U.S. foreign policy in the post-Cold War world, the wars in the Balkans offered a second. Before 1991 Yugoslavia was composed of six republics. But in June of that year, when Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic began to stoke nationalist flames and increase Serb dominance, the republic of Slovenia seceded, sparking a relatively painless ten-day war. Croatia, which declared independence at the same time, faced a tougher exit. Because Croatia had a sizable Serb minority and a picturesque and lucrative coastline, the Yugoslav National Army (JNA) refused to let it go. A seven-month war left some 10,000 dead and 700,000 displaced from their homes. It also introduced the world to images of Serb artillery pounding civilians in towns like Dubrovnik and Vukovar. By late 1991 it was clear that Bosnia (43 percent Muslim, 35 percent Orthodox Serb, and 18 percent Roman Catholic Croat), the most ethnically heterogeneous of Yugoslavia's republics, was in a bind. If Bosnia remained a republic within rump Yugoslavia, its Serbs would receive the plum jobs and educational opportunities, whereas Muslims and Croats would be marginalized and likely physically abused under Milosevic's oppressive rule. But if it broke away, its Muslim citizens would be especially vulnerable because they did not have a parent protector in the neighborhood: Serbs and Croats in Bosnia counted on Serbia and Croatia for armed succor, but the country's Muslims could rely only upon the international community.

The seven members of the Bosnian presidency (two Muslims, two Serbs, two Croats, and one Yugoslav) turned to Europe and the United States for guidance on how to avoid bloodshed. Western diplomats instructed Bosnia's leadership to offer human rights protections to minorities and to stage a "free and fair" independence referendum. The Bosnians by and large did as they were told. In March 1992 they held a referendum on independence in which 99.4 percent of voters chose to secede from Yugoslavia. But two Serb members of the presidency, who were hardliners, had convinced most of Bosnia's Serbs to boycott the vote.' Backed by Milosevic in Belgrade, both Serb nationalists in the presidency resigned and declared their own separate Bosnian Serb state within the borders of the old Bosnia.The Serb-doniinatedYugoslav National Army teamed up with local Bosnian Serb forces, contributing an estimated 80,000 uniformed, armed Serb troops and handing almost all of their Bosnia-based arsenal to the newly created Bosnian Serb Army. Although the troops changed their badges, the army vehicles that remained behind still bore the traces of the letters "JNA." Compounding matters for the Muslims and for those Serbs and Croats who remained loyal to the idea of a multiethnic Bosnia, the United Nations had imposed an arms embargo in 1991 banning arms deliveries to the region. This froze in place a gross imbalance in Muslim and Serb military capacity. When the Serbs began a vicious offensive aimed at creating an ethnically homogenous state, the Muslims were largely defenseless.

Map of Yugoslavia, depicting Serb gains, 1991-1995.

In 1991 Germany had been the country to press for recognizing Croatia's independence. But in April 1992 the EC and the United States took the lead in granting diplomatic recognition to the newly independent state of Bosnia. U.S. policymakers hoped that the mere act of legitimating Bosnia would help stabilize it. This diplomatic act would "show" President Milosevic that the world stood behind Bosnian independence. But Milosevic was better briefed. He knew that the international commitment to Bosnia's statehood was more rhetorical than real.

Bosnian Serb soldiers and militiamen had compiled lists of leading Muslim and Croat intellectuals, musicians, and professionals. And within days of Bosnia's secession from Yugoslavia, they began rounding up nonSerbs, savagely beating them, and often executing them. Bosnian Serb units destroyed most cultural and religious sites in order to erase any memory of a Muslim or Croat presence in what they would call "Republika Srpska"2 In the hills around the former Olympic city of Sarajevo, Serb forces positioned heavy antiaircraft guns, rocket launchers, and tanks and began pummeling the city below with artillery and mortar fire.

The Serbs' practice of targeting civilians and ridding their territory of non-Serbs was euphemistically dubbed etnifko fi.cenje, or "ethnic cleansing," a phrase reminiscent of the Nazis' Sduberunq, or "cleansing," of Jews. Holocaust historian Raul Hilberg said of the Nazi euphemism: "The key to the entire operation from the psychological standpoint was never to utter the words that would be appropriate to the action. Say nothing; do these things; do not describe them."' The Khmer Rouge and Iraqi Northern Bureau chief al-Majid had followed a similar rule of thumb, and Serb nationalists did the same.

As the war in Bosnia progressed, outsiders and insiders relied on the phrase "ethnic cleansing" to describe the means and ends employed by Serb and later other nationalistic forces in Bosnia. It was defined as the elimination of an ethnic group from territory controlled by another ethnic group. Although the phrase initially chilled those who heard it, it quickly became numbing shorthand for deeds that were far more evocative when described in detail.

The phrase "ethnic cleansing" meant different things on different days in different places. Sometimes a Serb radio broadcast would inform the citizenry that a local factory had introduced a quota to limit the number of Muslim or Croat employees to 1 percent of the overall workforce. Elsewhere edicts would begin appearing pasted around town, as they had in 1915 in the Ottoman Empire.These decrees informed non-Serb inhabitants of the new rules. In the town of Celinac, near the northern Bosnia town of Banja Luka, for instance, the Serb "war presidency" issued a directive giving all non-Serbs "special status." Because of "military actions," a curfew was imposed from 4 p.m. to 6 a.m. Non-Serbs were forbidden to:

• meet in cafes, restaurants, or other public places

• bathe or swine in the Vrbanija or Josavka Rivers

• hunt or fish

• move to another town without authorization

• carry a weapon

• drive or travel by car

• gather in groups of more than three men

• contact relatives from outside Celinac (all household visits must be reported)

• use means of communication other than the post office phone

• wear uniforms: military, police, or forest guard

• sell real estate or exchange homes without approval.'

Sometimes Muslims and Croats were told they had forty-eight hours to pack their bags. But usually they were given no warning at all. Machinegun fire or the smell of hastily sprayed kerosene were the first hints of an imminent change of domicile. In virtually no case where departure took place was the exit voluntary. As refugees poured into neighboring states, it was tempting to see them as the byproducts of war, but the purging of non-Serbs was not only an explicit war aim of Serb nationalists; it was their primary aim.