A Puzzle in a Pear Tree (9 page)

14

THE CROWD IN FRONT OF THE CHURCH HAD SWELLED. THE spectacular nature of the crime, with the Virgin Mary tumbling headlong from the stable, had drawn the townspeople as well as the sightseers who had driven up to see the Nativity. Grumbling, Sam Brogan had taken on the job of keeping them back. Even so, they filled the road, making it impossible to drive around the green.

Chief Harper and his contingent from the crèche had just reached the church when a puce Volkswagen Super-beetle careened by and skidded to a stop inches from the crowd.

Rupert Winston erupted from the door. The eccentric director looked as flamboyant as ever in a full-length suede overcoat, felt hat, and six-foot-long scarf of scarlet velvet. “Is it true?” he cried, playing to the crowd, the heavens, and the last row of the balcony. “Is she dead? Is Becky really dead?”

“Not so you could notice,” Becky Baldwin said.

Rupert Winston’s face ran a gamut of emotions that could have served for an actor’s audition piece. “Thank God!” he exclaimed. “It seemed too awful to be true, and yet! . . . And yet! . . . Thank God you’re safe!” The hollow smile on his face froze as realization dawned. The reaction was so hammy Cora couldn’t tell if he really was surprised, or was simply emoting. “Then what’s

wrong

?”

“One of the other girls is dead,” Cora informed him.

“Oh, how awful!” he cried, though it obviously wasn’t nearly as awful as if it had been Becky Baldwin. “Who is it?”

Maxine Doddsworth flung herself into the director’s arms. “It’s Dorrie, Mr. Winston! Dorrie’s dead!”

“Oh, my God!” Rupert pried himself from her clutches, held her at arm’s length. “Are you sure, Maxine? Are you sure it’s her?”

“It’s her,” Chief Harper said. “We have a positive ID. Did you know the girl?”

“She was in my play.”

Cora Felton frowned. “Really? What was she?”

“Oh, no,” Rupert said. “Not the Christmas pageant. The high school play. Dorrie was in

The Seagull.

”

“So, she was an actress,” Cora mused. “Interesting.”

Aaron Grant pushed his way through the crowd. “What’s interesting? What have we got? Murder?”

Chief Harper snorted in disgust. “This is getting out of hand. I’d like to remind you that all we’ve got at the present time is a potentially suspicious death. Until we know different, there’s nothing to report.”

“What isn’t there to report on?” Aaron persisted.

Sherry grabbed him by the arm. “It’s all right, Aaron. I’ll fill you in.”

Aaron turned at the sound of her voice, then stared. “Why are you a cop? I thought you were a virgin.”

“Oh, right. I gotta get these clothes back to Dan Finley.”

“Yes, you do,” Chief Harper said. “And then send him out here to clear the street. There’s nothing more to see, and there’s nothing to report. You got that, Aaron? Let’s have no irresponsible journalism here. It’s almost Christmas. This is no time for another media circus.” Bakerhaven had had its share of media circuses since Cora Felton moved to town.

“If it’s a natural death, I’ll play it down,” Aaron said.

“See that you do.”

As Sherry and Aaron hurried off in the direction of town hall, Sam Brogan detached himself from the crowd and ambled over.

“What’s up, Sam?” Chief Harper asked.

“Dan Finley’s riding herd on the witnesses. He’ll be glad to get his coat back.” Sam jerked his thumb. “Is that Maxine Doddsworth over there?”

“Yeah, why?”

“She’s the last one. Been roundin’ up anyone who was in that stable thing the same time as the victim. All kids, ’cept for Miss Carter.”

“Anyone see anything?”

“ ’Course not. Ask ’em yourself if you want, they’re all in town hall. Best bet is the boyfriend. He was holdin’ her when she took the plunge.”

“Could you keep it down?” Chief Harper warned. “Miss Doddsworth was Dorrie Taggart’s best friend.”

“So I understand. Dorrie relieved her, which puts Maxine right in the soup. Same as Miss Carter.”

“Excuse

me

,” Cora Felton warned.

Sam Brogan shrugged. “I don’t make the facts, I just report ’em.” He flipped open his notebook. “Then there’s Alfred Adams.”

“Who’s that?” Harper asked.

“He’s the Joseph Dorrie’s boyfriend relieved.”

“Why’s he important?”

“According to the schedule, the Marys change shifts on the hour, the Josephs at a quarter past. So Alfred Adams comes on at ten-fifteen, leaves at eleven-fifteen. He’s in place at eleven o’clock when Dorrie relieves her friend Maxine. He’s there for the first fifteen minutes the decedent plays Mary, until he’s relieved by the boyfriend, Lance Ridgewood.”

“And he saw . . . ?”

“Nothing, natch. Alfred Adams is a simpleminded lout. He’s a high school senior—I guess they all are—and a member of the tech crew. He spent the mornin’ hangin’ lights for the Christmas pageant. Got caught up in his work and lost track of time. Was a good five minutes late for his shift.”

“Anything to that?” Cora asked avidly.

Sam shook his head. “He got there ten-twenty ’stead of ten-fifteen, but it don’t mean a thing ’cause Dorrie didn’t get there till eleven. He was there from the time she arrived at eleven till he was relieved at eleven-fifteen. A fifteen-minute window of opportunity during which he could have killed her. If he did, I’ll buy you lunch.”

“Uh-huh,” Harper grunted.

Sam flipped a page. “The boyfriend Lance Ridgewood’s the other side of the coin. Class president, captain of the debate team. Early acceptance to Yale. If I was makin’ book, my money’d be on him. If it wasn’t the women.”

Harper frowned.

On the far side of the crowd a car pulled to a stop, and the trim figure of Barney Nathan emerged. A few prissy, clipped

Excuse me

’s parted the crowd, and allowed him to stride up to the chief.

“I don’t want you to take this as a precedent,” he announced. “And don’t expect me to be so fast next time.”

“You have the cause of death?”

“Yes, I do, and you’re not going to like it.”

“What is it?” Chief Harper asked.

“Poison.”

“Poison! How is that possible! She was in the stable. She didn’t eat or drink anything. Are you saying she was poisoned before she posed, some slow-acting poison that didn’t take effect until she was kneeling there in front of everyone?”

“I’m saying,” Dr. Nathan responded dryly, “that she was killed by a quick-acting poison injected directly under the skin.”

“You mean she was stuck with a hypodermic?” Chief Harper was incredulous. “That’s impossible. She was on public display in front of half a dozen witnesses.”

“That’s your problem, not mine,” Dr. Nathan replied serenely. “But I don’t think she was stuck with a hypodermic.”

“And why not?” The chief sounded irritated.

“Because, unless I’m very much mistaken, I have the murder weapon right here.”

Dr. Nathan reached in his coat pocket, pulled out a plastic bag, and held it up for all to see. In it was something brightly colored red and blue. At first glance it resembled the feathers of a man’s hat.

Cora Felton, who was closest to the doctor, took one look and gasped.

It was a dart.

15

CORA FELTON WAS SNEAKING OUT OF TOWN HALL. IT HAD been twenty minutes since the doctor had produced the dart, and Chief Harper and Jonathon Doddsworth were inside taking witness statements. Ordinarily, Cora would have loved to stay, but Doddsworth had deemed her a witness, and refused to let her listen in. Cora had deemed Doddsworth something far less flattering, and scooted out as soon as she could.

Cora came out the door to find Rick Reed, the handsome, young, ambitious, and totally clueless Channel 8 on-camera reporter, and his film crew interviewing Becky Baldwin on the steps. Seeing Cora distracted Rick, made him fluff a question. Cora smiled. The reporter was hopelessly torn. On the one hand, Cora had just come from the police and would make a better interview. On the other hand, Rick had a crush on Becky, and Cora was unlikely to give him the time of day.

Cora solved his dilemma by announcing, “No comment, ” and sailing on by. It occurred to her it was the nicest thing she’d ever done for him.

As Cora drew near the church, Harvey Beerbaum detached himself from the crowd and descended on her. The fastidious linguist was as agitated as she’d ever seen him. “What’s going on?” he demanded. “No one knows anything, but everyone thinks they do. There are rumors going around of the most outlandish sorts. The young lady was shot with an arrow. She was poisoned with every sort of beverage from herbal tea to diet soda—decaffeinated, no less. She was stabbed, strangled, garrotted, bludgeoned, or smothered with SaranWrap.”

“SaranWrap?”

“Positioned over the mouth and nose so that she could not breathe. Are any of those scenarios grounded in reality?”

“It’s really not my place to discuss scenarios.”

“Balderdash!”

“Balderdash?”

“Cora, it’s me, Harvey. What do you know?”

“Not much more than you do, Harvey,” Cora said with insincerity.

He looked around, lowered his voice confidentially. “Then tell me this. Was there a letter?”

“You mean a puzzle?”

“Yes. A puzzle poem. By rights there should be, if this is

our

killing. So was there one?”

Cora shook her head. “None was found.”

“That’s odd,” Harvey mused. “Then maybe this was unrelated.”

“Not likely,” Cora told him. “The victim should have been Becky Baldwin.”

Harvey scrunched up his nose. “That’s a heartless thing to say.”

“I mean the girl took Becky’s time slot. Haven’t any of the rumors alluded to that?”

“Not really. Becky was doing a there-but-for-the-grace-of-God-go-I routine, but I believed it was simply histrionics.” Harvey frowned. “Well, in that case, there most certainly should be a poem. Otherwise, the setup makes no sense. Is it possible the authorities found the poem and didn’t divulge it?”

“No chance. I was there when it happened. At the crime scene. Before the cops were. Trust me, there was no poem there.”

“Did you look for a murder weapon?”

“I didn’t find any murder weapon.”

“Are you saying there was none to find?”

“You should have been a lawyer, Harvey. You have a positive gift for cross-examination.”

“Not at all. I’m merely listening to what you say. It’s very like solving a puzzle, really. Decoding your answers to my questions. And I don’t believe you answered my last one. About the murder weapon. It seems to me I’ve inquired several times without getting an answer.”

“Well, speaking of rumors . . .” Cora’s voice trailed off invitingly.

“Yes?”

“You suppose I could tell you something without you putting it around?”

“Of course. My lips are sealed,” Harvey vowed.

“The doctor found a poisoned dart in Dorrie’s clothing. He thinks it’s the cause of death.”

“A poisoned—!”

“Could you keep your voice down? Now, assuming the killer wasn’t one of the actors, a person would have to be right in front of the stable to throw a dart. Or to lean over and stick it in.”

“Wouldn’t the actors have seen something?”

“Yes,” Cora said. “But if they had, the police would be arresting that person now. The fact the police are still questioning them is a good indication the actors don’t know squat.”

“Excellent point,” Harvey said. Clearly, approaching the murder as a logic problem delighted him. “How is that possible?”

“Don’t know. But if the actors didn’t see something, maybe someone else did. You notice how the stable is set up facing the church?”

Cora pointed at a hawk-nosed man hanging out at the edge of the crowd. “Isn’t that the minister over there near the bottom of the steps?”

“That’s the Reverend Kimble, of course,” Harvey said. “Surely you know him.”

Cora, who couldn’t remember the last time she’d been in a church without getting married, mumbled, “Yes, of course. Hard to tell at this distance. Listen, Harvey. The Reverend would certainly notice the Nativity. It occurs to me he might know something without being aware that he knows it. If you’re on speaking terms with him, I’m wondering if you could draw him out. Ask if there was anyone who might have thrown a dart.” She raised an admonitory finger. “Without tipping your hand that’s what you’re getting at, of course.”

“Gotcha,” Harvey said.

Cora had to pretend to cough in order to hide her amusement at how quickly the erudite grammarian plummeted into the vernacular at the prospect of pumping a witness. She watched as Harvey threaded his way through the crowd and engaged the Reverend in conversation. With satisfaction she noted that Harvey was directing the clergyman’s attention to the stable in the center of the green.

Cora had not had long to formulate her theory of the case, but she certainly had one. If the killer was not an actor in the tableau, then the attack on Dorrie had come from the front. That left two possibilities: the killer drove by in a car, or the killer came on foot. In the latter case, the killer would have needed someplace to hide.

While Harvey Beerbaum had the Reverend’s attention diverted, Cora slipped up the front steps of the Congregational church.

She entered and found herself in a small anteroom. In front of her, double doors led into the church itself. The doors were open, and Cora could see the pews for the parishioners, and the raised pulpit. Cora could imagine the Reverend Kimble in it, towering over his flock. She could also imagine him wandering through the church during the day, making it a most unattractive place to hide. Two closed doors off the foyer looked more promising. Disappointingly, both were locked with dead bolts. It occurred to Cora the Reverend Kimble had faith in both a higher power

and

modern security technology.

A narrow stairway in one corner of the foyer curved up and around. Cora tried it, found that it led to the organ loft. This was more like it. Even as she went up the stairs she could see a window in the front wall, where the killer could watch for the right time to strike. Cora checked it out. Sure enough, there was a perfect view of the stable, as well as the street below, where, she noted, Harvey Beerbaum was still chatting up the Reverend Kimble. It was the ideal vantage point, the ideal spot for a killer to lie in wait.

Cora frowned.

So what? From the road, ther twenty yards across the snow. Out for cover. No cover of any kind. snow . . .

There was no way, absolutely n get from the church to the stable every actor in the tableau.

Yet somehow the killer had.

Cora sighed.

She turned from the window to check out the organ.

She froze.

The organ was the old-fashioned kind, of elaborate, carved mahogany, with ivory keys, round labeled stops, burnished brass pipes, and wooden foot pedals.

Leaning up against the side of the organ was a long stick.

Taped to the top of the stick was a bright red envelope.

Cora’s heart began beating faster. She’d wanted a clue, but not this.

Not now.

Cora rushed back to the window. Apparently the Reverend Kimble hadn’t had much to say, because Harvey was done with him and was now looking around, probably for her. And the Reverend was headed straight for the church.

Damn!

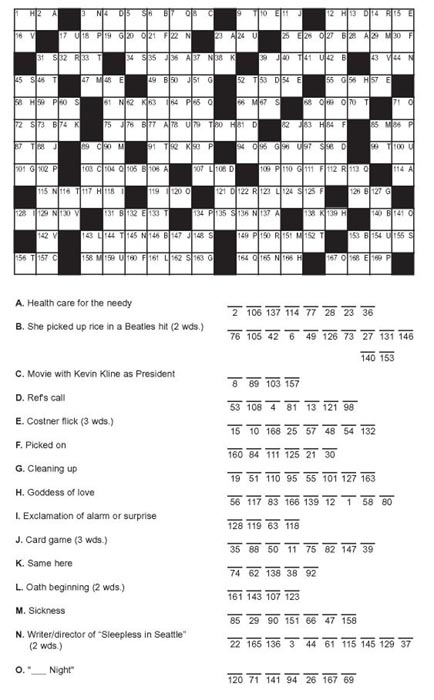

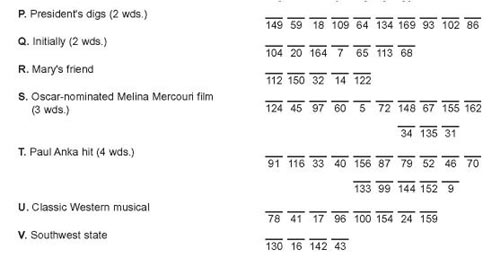

Cora raced back to the organ. She grabbed the envelope, ripped it open, pulled out the paper inside. Sure enough, it was another acrostic.

Cora was sweating, and it wasn’t just her wool overcoat. She looked at the puzzle in her hand and muttered a comment unlikely to be found in its solution . . . and most unseemly, given her surroundings.

Cora dropped to one knee. She shoved the puzzle back in the envelope and flung it on the floor. She rummaged through her floppy drawstring purse and began pulling out treasures dating back as far as husband number two. A lipstick. A key chain with a key to God-knows-what. A coin purse. A gun, fully loaded, and, yes, with the safety on. A theater ticket to

Cats,

untorn—funny, she must have never gone. A paper clip. Half a roll of wintergreen Life Savers. And—

A pair of eyeglasses.

An old pair, in rather poor condition. The lenses were scratched, the wire rims bent, the left earpiece was actually gone.

Perfect.

Cora sprang to her feet, threw the glasses on the floor, and stamped on them, hard. The lenses shattered.

Cora tore off her own glasses and jammed them deep in her purse. Hastily she stuffed in her other keepsakes. When she was done, she grabbed the red envelope and the mutilated glasses, leaped to her feet, swung the purse over her shoulder, and groped her way down the stairs.