A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy (21 page)

Read A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy Online

Authors: Thomas J. Cutler

After the Japanese aircraft returned to the six aircraft carriers that had launched them on their surprise attack, Pearl Harbor was a shambles. Nineteen ships were sunk or heavily damaged, including battleships

Arizona, Oklahoma, California, Nevada, Maryland, Tennessee, Pennsylvania,

and

West Virginia.

Ninety-two naval aircraft were destroyed and 31 damaged.

The Army lost 96 aircraft, with another 128 damaged. Casualties were enormous: 2,008 Sailors killed and 710 wounded; 109 Marines killed and 69 wounded; 218 Soldiers killed and 364 wounded; and 68 civilians killed and 35 wounded.

On the evening of 8 December, an American task force that had been at sea during the attack returned to Pearl Harbor. Admiral William F. Halsey, embarked in the carrier

Enterprise,

watched from the carrier's bridge wing as the ship made her way up the channel. A pall of smoke hung over the harbor, and the surface of the water was coated with an ugly blanket of fuel oil. The blackened skeletons of burned-out buildings lined the shore, the smells of death and destruction were everywhere and strong, but perhaps the worst sight of all was the broken remains of Battleship Row where the concentrated power of the Pacific Fleet had once resided.

Arizona,

or what little of her that remained, still burned. Little more than

California

's super-structure showed above the black water.

West Virginia

was a scorched hulk, and

Oklahoma

's underbelly turned skyward was the most unsettling sight of all. Staring at the devastation with a fierce intensity carved into his rugged features, Halsey was heard to snarl, “Before we're through with them, the Japanese language will be spoken only in hell!”

The Japanese had dared to tread upon the U.S. fleet. Now the rattlesnake was poised to strike.

On board the destroyer

McDermut,

Torpedoman's Mate Third Class Roy West sat at his battle station on the ship's torpedo mount amidships waiting for something to happen. He watched as a bit more perspiration than the 80-degree night would normally have drawn traced glistening paths down the face of the man nearest him. The tension had been building ever since the word had come down that the Japanese were coming up Surigao Strait and

McDermut

had received her battle instructions from the squadron commodore.

Roy West and the other men manning the torpedo mount did not know the details of the battle plan, but they did know the Japanese were expected to come up through the strait to the south of them and that

McDermut

and the other four ships of Destroyer Squadron 54 would attack with torpedoes when, and if, they came. The captain had seemed pretty certain that the Japanese would come when he spoke to the crew earlier over the ship's general announcing system, briefly explaining what was expected to happen and exhorting each man to do his best in the coming battle.

At about 2200, the ship had been ordered to “Condition I Easy,” which meant that all battle stations would be manned but that certain designated

doors, hatches, and scuttles could be briefly opened and shut to allow the men limited movement to make head calls or to deliver coffee and sandwiches. All around the ship the men passed the time according to individual needs. Some were very quiet, silently praying, while others joked loudly. A few invoked the seafarer's ancient rite of complaining, and some ventured to predict what the night would bring. Letters, pictures of wives, girlfriends, and dogs, and decks of playing cards emerged from denim pockets, and more cigarettes than usual flared in the ship's interior spaces where there were no munitions.

At

McDermut

's torpedo mount amidships, West listened as a young man nearby talked about the many virtues of his mother, and he watched as another man nervously fingered a small silver cross. One of the men, who consistently wore an air of bravado as though it were part of his Navy uniform, caught Roy's eye and grinned at him as if to say that all was routine and normal. But tiny strands of spittle between the man's lips said more about what was going on inside than did the forced grin.

The life jackets and helmets that always seemed a burdensome nuisance during drills now brought a mixed sense of foreboding and comfort as the minutes ticked slowly by. West had the almost constant, unsettling feeling of having just stepped in front of a speeding automobile, waiting helplessly while the vehicle careened toward him, tires screeching as the few feet of asphalt between them rapidly disappeared.

And still nothing happened.

Roy West and his shipmates were about to fight in one part of the largest naval battle in history at a place called Leyte Gulf in the Philippines. It was the night of 24â25 October 1944, and a lot had happened since the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The U.S. Navy had fought a long and arduous campaign across the Pacific, at places like Midway, Guadalcanal, and the Philippine Sea.

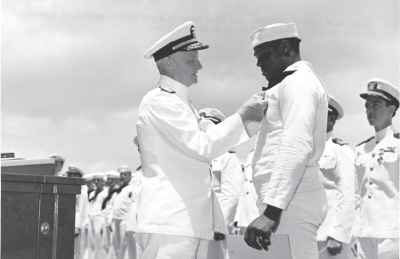

Dorie Miller had served in two more ships since

West Virginia

had gone to the bottom of Pearl Harbor. For his valor, the boxer-turned-gunner had received the Navy Cross, second only to the Medal of Honor. At the presentation ceremony on 27 May 1942, Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet, proved prescient when he said, “This marks the first time in this conflict that such high tribute has been made in the Pacific Fleet to a member of his race and I'm sure that the future will see others similarly honored for brave acts.” Indeed, many more Sailors of every race had shown their mettle as the Navy had beaten back a fanatical and capable enemy across the vast reaches of the Pacific.

Petty Officer Doris Miller receives the Navy Cross from Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific, 27 May 1942.

U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

The victories came with price tagsâmany of them hefty. Assigned to the newly constructed escort carrier USS

Liscome Bay

in the spring of 1943, Dorie Miller was serving in her during Operation Galvanic, the seizure of Makin and Tarawa atolls in the Gilbert Islands the following November. At 0510 on 24 November 1943, a Japanese submarine fired a torpedo into the carrier's stern. The aircraft bomb magazine detonated a few moments later, sinking the warship within minutes. Six hundred forty-six Sailors went down with the ship, Dorie Miller among them.

Sometime after 0200, Roy West and the other men at

McDermut

's torpedo stations sensed that the ship was no longer pacing monotonously at her patrol station but had changed course and speed. A quick look at the gyro repeater confirmed they were moving south. West heard someone nearby say, “This is it.” He felt the soft rustling of butterfly wings somewhere deep in his stomach.

Torpedoman's Mate Third Class Richard Parker's battle station was on the port bridge wing, along with the torpedo officer, Lieutenant (junior grade) Dan Lewis, who was running the port torpedo director. From their vantage point, Parker and Lewis had more information about what was happening, and Parker began passing the “gouge” over the sound-powered

phone system to the others at the various torpedo stations. West, whose battle station was gyro setter for torpedo mount number two, looked at the mount captain, Torpedoman's Mate Second Class Harold Ivey, as reports came in describing American PT boat attacks against the oncoming Japanese force. Several times the word

battleship

was used, and each time West and Ivey exchanged quick looks.

After a few more minutes, the luxuryâor curseâof idleness dissipated as things began to happen rapidly. Evidently,

McDermut

was closing on the enemy because a torpedo firing solution began to take shape. The men on both mounts began quickly matching pointers with the information coming down from the port torpedo director, cranking in gyro angle, alternately engaging and disengaging spindles, and occasionally taking a quick swipe at the beads of perspiration running down their faces. West concentrated hard as the glowing dials before him spun in a jerky dance of whirling numbers. Trying to ignore the thumping cadence of his heart, he worked the cranks just as he had done hundreds of times before in training for this moment.

The destroyer heeled to port as her rudder went over, and she came quickly right about 40 degrees. As she steadied up, West knew his ship must be directly paralleling the target's approach course, on the reciprocal, because there was suddenly no gyro error to correct. Assuming the enemy would continue on his present course and speed, this meant

McDermut

had a near perfect firing solution and an optimum chance for success. It also meant the Japanese ships were closer to Roy West than they had ever been before, and they were probably coming directly at him at a relative speed of nearly fifty knots.

For nearly two hours in the subterranean darkness of USS

Remey

's CIC, the squadron commodore, Captain J. G. Coward, had been monitoring reports from the PT boats farther south in the strait. Despite the excited confusion in the reports, one thing was clear: there was a sizable Japanese force headed up Surigao Strait.

When it appeared that the Japanese had passed the last section of PTs, Coward sent a message to Admiral Jesse Oldendorf saying he was taking his destroyers down the strait.

Remey

led two other tin cans down the eastern side of the strait, while

McDermut

and

Monssen

proceeded southward along the western side.

Before long, radar revealed what no human eye could see. Like tiny green ghosts, several faint contacts flared, then faded on the screen, bearing 184 degrees, range thirty-eight thousand yards. Believing that he could better control his destroyers in a night battle from the bridge, Captain Coward

left CIC and emerged into the humid night air. It was darker there than it had been in

Remey

's CIC.

Soon a report came from CIC that seven enemy ships could be discerned on the radar. From the relative sizes of the pips, the radar men evaluated them as two battleships, a cruiser, and four destroyers. As the American destroyers raced headlong toward the contacts, excited voices called out the diminishing radar ranges. Radio speakers crackled with reports in a chorus as indiscernible to the untrained ear as that heard by the uninitiated at an opera.

Â

“SKUNKS BEARING ONE EIGHT FOUR DISTANCE FIFTEEN MILES, OVER.”

“STANDBY TO EXECUTE SPEED FOUR. JACK TAR AND GREYHOUND ONE, ACKNOWLEDGE.”

“THIS IS JACK TAR, WILCO.”

“THIS IS GREYHOUND ONE, WILCO.”

“THIS IS BLUE GUARDIAN, I AM COMING LEFT TO ZERO NINER ZERO TO FIRE FISH.”

Â

And so on.

As the two sections of destroyers converged on the Japanese column, Coward assigned targets to his ships. Five U.S. destroyers, with a total displacement of about 12,500 tons, were about to engage two battleships, a heavy cruiser, and four destroyers, whose tonnage topped a hundred thousand. Undeterred by this unsettling fact, the American destroyers pressed in for the attack.

In

McDermut,

now charging down the western side of Surigao Strait, Richard Parker passed the word over the sound-powered phone circuit that the three tin cans on the other side of the strait were launching torpedoes at the Japanese.

From his perch atop the torpedo tubes amidships, Roy West peered out over the port side of the ship, trying to see if he could make out anything on the eastern side of the strait. His eyes probed the inky darkness as he heard the command to release spindles.

Suddenly, there was a burst of light in the sky above

McDermut

as a Japanese star shell ignited. The brightly burning flare hanging from the shrouds of its miniature parachute seemed fixed in the sky above them as it cast an eerie gray-white light on the sea. West glanced about and saw

Monssen

revealed in the ghostly pallor, and he hoped that neither destroyer was as visible to the Japanese. From somewhere ahead, a green searchlight began sweeping the sea, and West knew he was in the thick of things.

A moment later, the command to “commence firing” came down from the bridge, and West could feel the expulsion of the five torpedoes beneath him as they leaped from the ship into the boiling sea. Both of

McDermut

's quintuple mounts fired full salvoes. Ten “fish” swam off into the night in pursuit of Japanese steel.

Monssen

also fired a full salvo so that ten more torpedoes were making Surigao Strait a very dangerous place to be.

West and the other torpedo men quickly secured their mounts and gathered around Chief Virgil Rollins, who was peering at a stopwatch in the subdued red glow of his flashlight. As the group waited anxiously for the expected run time of the torpedoes to expire, they could feel

McDermut

heeling sharply over as she came about to dash back up the strait. The wind swept across her decks as she came hard to starboard, and the whole world seemed to be spinning out of control. Suddenly, West could see the faces of his shipmates in a ghastly green light and knew that the searchlight had found them. He felt the concussion of a nearby detonation and was astonished to see a large column of water rise up out of the sea off the port side. Several more rounds exploded so close aboard that

McDermut

's weather decks were drenched in a shower of warm salt water.