A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962 (80 page)

Read A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962 Online

Authors: Alistair Horne

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #War

According to Bernard Tricot, de Gaulle’s wider strategy was as follows: “If Tunis replied in a negative or dilatory fashion to the 14 June speech, the negotiations for a partial cease-fire would be resumed. If, on the contrary, the G.P.R.A. appeared to commit itself genuinely along the road to peace, the leaders of Wilaya 4 would suspend negotiations.” This seems curiously naïve, and totally insensitive to the intolerable danger to which Si Salah and his fellow “renegades” would thus be submitted. But the whole truth may not have been quite so guileless. On the basis of information provided by Krim after the war, General Jacquin insists that on 26 March — only a few days after the first contacts had been taken up with Si Salah, under a veil of total secrecy — Krim received a “leak” from the French government revealing that Wilaya 4 was proposing a separate cease-fire. Thus it seems that de Gaulle may throughout have regarded “Operation Tilsit” chiefly as a powerful lever with which to prise the G.P.R.A. into negotiations on his terms — the glistening goal which had eluded him all along.[

4

] The implied menace was clear; either deal with me for a cease-fire, or I will conclude a separate peace with your subordinates.

On the other hand, de Gaulle himself was under strong counter-pressures at approximately this time. In May 1960 Krim and Boussouf were on their way back from the most high-powered and successful visit that the F.L.N. had yet made to Peking and Moscow, accompanied by well-publicised promises of greatly augmented support from the Communist bloc. As always, there was nothing which made de Gaulle more nervous than the fear of being caught in a Communist pincer in Algeria. Thus, here was a Machiavellian political game, with both de Gaulle and the G.P.R.A. playing for higher stakes than Si Salah; and with success almost bound to make inevitable the sacrifice of the pawns who had put their trust in de Gaulle. Who would win? And would the ends justify the means?

Melun

The G.P.R.A.’s response to de Gaulle’s broadcast of 14 June was significantly swift. Within the week had come their acceptance; on the 25th the first F.L.N. delegation ever to fly openly to France to discuss peace arrived at Orly, enveloped in massive security precautions. Leading them were the youthful and quick-witted Ben Yahia and Maître Ahmed Boumendjel, a gallicised lawyer well-known to the Paris Bar, who had joined the F.L.N. following the “suicide” of his brother, Ali, during the Battle of Algiers. Boumendjel, a portly figure exuding bonhomie, epitomised the cheerful self-confidence the Algerians displayed on arrival. At the head of the receiving delegation was Roger Moris, de Gaulle’s Secretary-General for Algerian Affairs, supported by Colonel Mathon, who had been so closely involved in “Operation Tilsit”. Moris was not perhaps the happiest of choices, in that he was generally regarded as an apostle of

Algérie française

. The Algerians were conducted to the Louis XIII prefecture in the nearby town of Melun, where, in the words of Boumendjel, they were kept as in a “golden cage”. Sleeping, eating and conferring in the prefecture, over the ensuing five days they were not permitted to leave its grounds, or have any contact with the journalists clustered outside the iron railings — de Gaulle having decreed a total Press silence. The only link allowed with the outer world was a direct telephone line to the G.P.R.A. in Tunis; there was absolutely no question of any communication with Ben Bella in

his

“golden cage”. The Algerians felt they were treated throughout with a certain arrogance by de Gaulle, to whom their French opposite numbers reported back each evening.

Under these auspices the conference opened unhopefully with each side repeating its own well-worn and mutually irreconcilable formulas for peace. The one was a step-by-step approach, with the French insisting that a cease-fire must precede negotiations; the other global, declaring with equal rigidity that a cease-fire could not be regarded separately from an overall political settlement. De Gaulle was swiftly disabused of any hopes that the emissaries had come prepared for a speedy acceptance of his

drapeau blanc

when Boumendjel demanded that there should now be direct talks between de Gaulle himself and Ferhat Abbas — or, preferably, a liberated Ben Bella. Apart from offending the niceties of French diplomatic custom, which required elaborate preparations in advance of such a “summit”, it was clear to de Gaulle that this was but a skilful move to gain

de facto

recognition for the G.P.R.A. A frosty refusal was passed down from Olympus: how could there be such concessions while murders and ambushes continued in Algeria? Next, the Algerians requested that at least a member of the French government of ministerial rank should take part in the talks. After four days of the deaf speaking to the deaf, de Gaulle unilaterally broke off the talks. On the 29th the Algerians departed in a cold but courteously correct atmosphere. The following week Ferhat Abbas was declaring in the language of the hard-liners: “Independence is not offered, it is seized…. The war may still continue a long time.” As the logical diplomatic follow-up, fresh threats of the F.L.N. turning its face further towards the Eastern bloc were soon in the air, with Abbas explaining: “We would rather defend ourselves with Chinese arms than allow ourselves to be killed by the arms of the West….”

Whichever way one may look at it, Melun was a total defeat for de Gaulle, while it gave the F.L.N. their second political victory of the year — if “Barricades Week” may be reckoned the first. As seen by the uncommitted Muslims of Algeria, the G.P.R.A. had been

invited

by de Gaulle, but it was on

their

initiative that they had returned home — both sure signs of strength. From this moment, claims Philippe Tripier, they “adopted an equivocal attitude” towards de Gaulle, attributing to him “the posture of the defeated”. To the French investors on whom Delouvrier counted for the realisation of the Constantine Plan, the mere fact that de Gaulle had begun negotiations at all was a major deterrent, while, to the “silent majority” in France as a whole the fact that they had failed came as an unmistakable disappointment. Despite de Gaulle’s clamp-down on Press coverage, the F.L.N. — consonant with its untiring pursuit of “externalising the war” — had gained another valuable world platform and much beneficial publicity. Though de Gaulle might continue to protest that he would not recognise the G.P.R.A. as a negotiating partner, by the mere presence of its emissaries at Melun it had got a first foot in the door which de Gaulle would never be able to dislodge. This was what, from his prison cell, Ait Ahmed had perceptively predicted, and urged upon the G.P.R.A., some six months earlier (and it was a lesson that was certainly not lost upon the negotiators of North Vietnam in their tediously protracted appearances in Paris over a decade later). Seen in the perspective of time, it seems clear that — although Ferhat Abbas might still have desired purposeful negotiations in that summer of 1960 — the G.P.R.A. had come to Paris with no other intention than to place its foot in the door, and then withdraw leaving it there.

No, there had been one other intention — to recoup from the Si Salah affair.

In both respects this strategy of the G.P.R.A. “hard-liners” succeeded admirably, drawing de Gaulle into a cunningly laid trap. De Gaulle seems to have totally miscalculated the hand he felt had been dealt him by “Operation Tilsit”, and it may well have been one of the most disastrous miscalculations of the whole war — on a number of levels. Certainly, as far as any aim of using Si Salah as a lever to bring the G.P.R.A. to the conference table was concerned, de Gaulle fell dismally between two stools — losing Si Salah and gaining nothing from the other. Just how much might have been achieved by “Operation Tilsit” remains a matter of bitter controversy between the senior army officers concerned in it and those close to de Gaulle, like Bernard Tricot. The former claim it to be one of the capital events of the war, a full vindication of the Challe strategy. If carried through, they say, it could at its lowest have resulted in creating a “hole” right in the geographical centre of the revolt, covering a third of the area of Algeria and splitting the east from the west. At its highest, it would have deprived the F.L.N. of any claim to be the sole representative of nationalist Algeria, and have led eventually to a separate peace on terms permitting the continued existence of the

présence française

.[

5

] And once the fighting war had died away in the “interior”, it would be extremely difficult to rekindle. Algeria might have been spared more than a year of war.

Whether these arguments are realistic or not is almost less important than the fact that General Challe, in particular, believed them and they were to play a decisive role in his own future actions. As Yves Courrière remarks, the Si Salah fiasco “was the point of departure for what, less than a year later, was to be called the Revolt of the Generals. For them, following his meeting with Si Salah, de Gaulle committed an act of betrayal on 14 June 1960.”

Though the whole Si Salah[

6

] and Melun episode was far from being de Gaulle’s finest hour, coming so soon after his precarious recovery from “the Barricades”, it goes some way to illustrate both the complexities of the pressures upon him, as well as the essential loneliness of his position. There was one final point: whatever the potential of Si Salah, by renouncing him in favour of talks with the G.P.R.A. emissaries, de Gaulle was in effect dealing, on behalf of the G.P.R.A., yet another blow at the evanescent “third force” in Algeria. Even if he had just intended to use Si Salah as the lever to make the G.P.R.A. negotiate, the fact of their accepting it meant that de Gaulle — regardless of his protests to the contrary — would eventually be forced to negotiate solely with the F.L.N., because there would be no one else, no other

interlocuteur valable

. Thus, from “Tilsit” and Melun onwards the battle between France and the F.L.N. now began to depart from the blood-stained

bled

of Algeria for higher realms of politics and diplomacy.

23.

Ratonnade

.

24. “Barricades Week”, January 1960. Rival leaders Pierre Lagaillarde and Joseph Ortiz.

25.

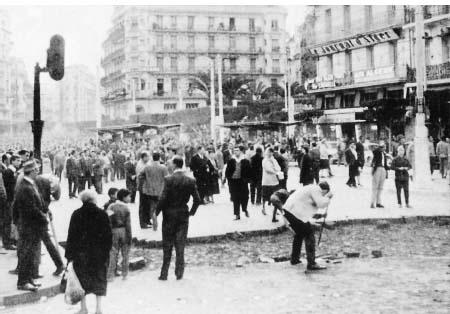

Above:

“Barricades Week”, Algiers. Demonstrators tear up the cobbles to make barricades while a huge crowd gathers.

26.

Below:

December 1960. Rue Michelet: scenes reminiscent of Budapest, 1956, as

pied noir

“ultras” demonstrate against de Gaulle.