A Short History of the World (34 page)

Read A Short History of the World Online

Authors: H. G. Wells

The Rise of Germany to Predominance in Europe

We have told how after the convulsion of the French revolution and the Napoleonic adventure, Europe settled down again for a time to an insecure peace and a sort of modernized revival of the political conditions of fifty years before. Until the middle of the century the new facilities in the handling of steel and the railway and steamship produced no marked political consequences. But the social tension due to the development of urban industrialism grew. France remained a conspicuously uneasy country. The revolution of 1830 was followed by another in 1848. Then Napoleon III, a nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, became first President, and then (in 1852) Emperor.

He set about rebuilding Paris, and changed it from a picturesque seventeenth-century insanitary city into the spacious Latinized city of marble it is today. He set about rebuilding France, and made it into a brilliant-looking modernized imperialism. He displayed a disposition to revive that competitiveness of the Great Powers which had kept Europe busy with futile wars during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The Tzar Nicholas I of Russia (1825â1856) was also becoming aggressive and pressing southward upon the Turkish Empire with his eyes on Constantinople.

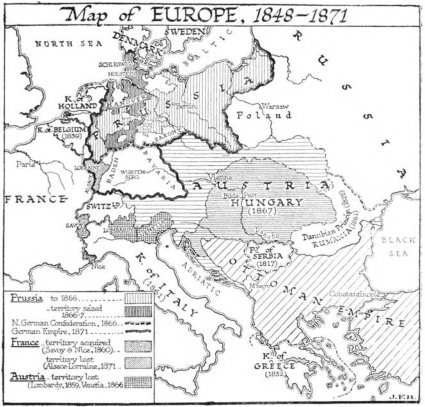

After the turn of the century Europe broke out into a fresh cycle of wars. They were chiefly âbalance-of-power' and ascendancy wars. England, France and Sardinia assailed Russia in the Crimean war in defence of Turkey; Prussia (with Italy as an ally) and Austria fought for the leadership of Germany, France liberated north Italy from Austria at the price of Savoy, and Italy gradually unified itself into one kingdom. Then Napoleon

III was so ill advised as to attempt adventures in Mexico during the American civil war; he set up an Emperor Maximilian there and abandoned him hastily to his fate â he was shot by the Mexicans â when the victorious Federal government showed its teeth.

In 1870 came a long-pending struggle for predominance in Europe between France and Prussia. Prussia had long foreseen and prepared for this struggle, and France was rotten with financial corruption. Her defeat was swift and dramatic. The Germans invaded France in August, one great French army under the Emperor capitulated at Sedan in September, another

surrendered in October at Metz, and in January 1871, Paris, after a siege and bombardment, fell into German hands. Peace was signed at Frankfort surrendering the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine to the Germans. Germany, excluding Austria, was unified as an empire, and the King of Prussia was added to the galaxy of European Caesars, as the German Emperor.

For the next forty-three years Germany was the leading power upon the European continent. There was a Russo-Turkish war in 1877â8, but thereafter, except for certain readjustments in the Balkans, European frontiers remained uneasily stable for thirty years.

The New Overseas Empires of Steamship and Railway

The end of the eighteenth century was a period of disrupting empires and disillusioned expansionists. The long and tedious journey between Britain and Spain and their colonies in America prevented any really free coming and going between the home land and the daughter lands, and so the colonies separated into new and distinct communities, with distinctive ideas and interests and even modes of speech. As they grew they strained more and more at the feeble and uncertain link of shipping that had joined them. Weak trading-posts in the wilderness, like those of France in Canada, or trading establishments in great alien communities, like those of Britain in India, might well cling for bare existence to the nation which gave them support and a reason for their existence. That much and no more seemed to many thinkers in the early part of the nineteenth century to be the limit set to overseas rule. In 1820 the sketchy great European ‘empires’ outside of Europe that had figured so bravely in the maps of the middle eighteenth century, had shrunken to very small dimensions. Only the Russian sprawled as large as ever across Asia.

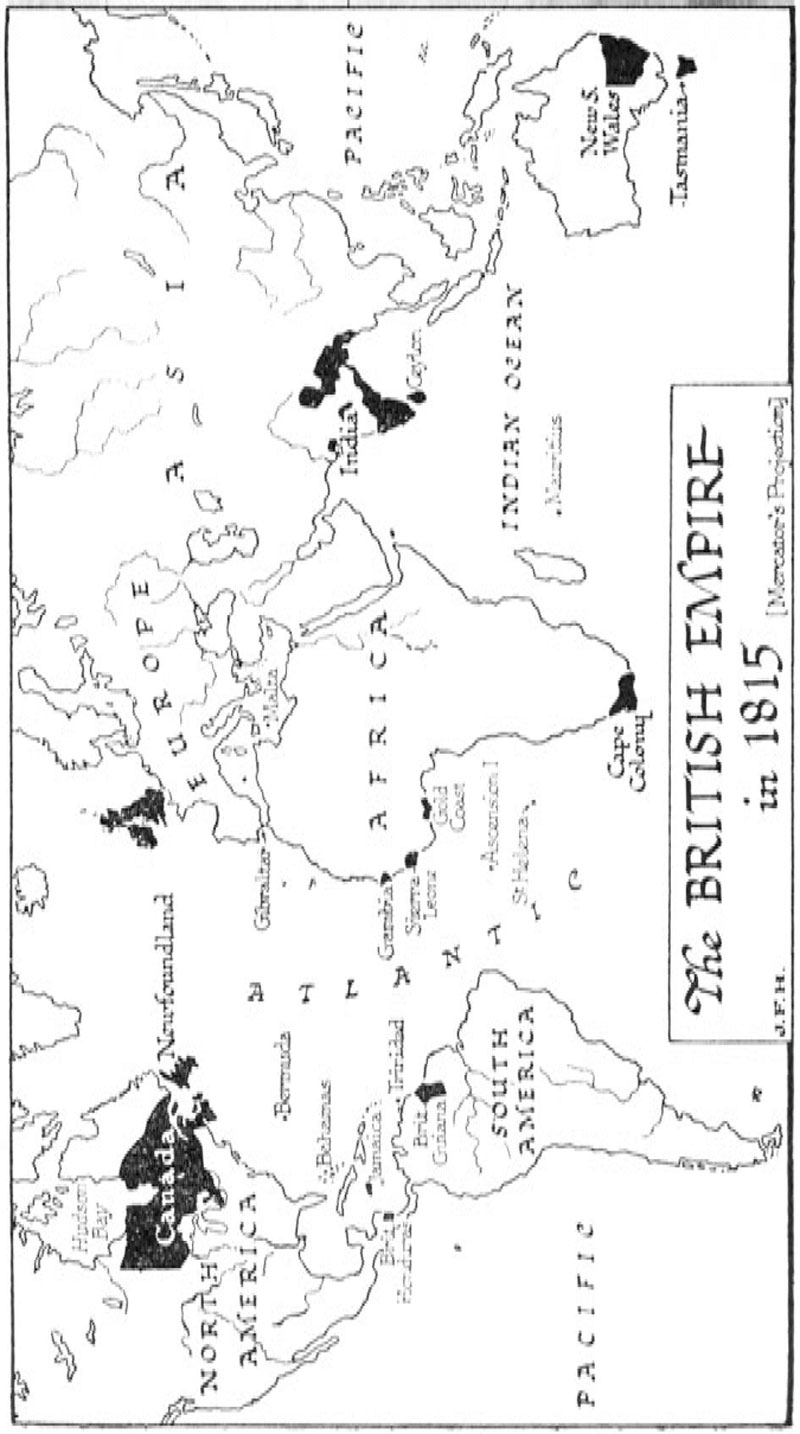

The British Empire in 1815 consisted of the thinly populated coastal river and lake regions of Canada, and a great hinterland of wilderness in which the only settlements as yet were the fur-trading stations of the Hudson Bay Company, about a third of the Indian peninsula, under the rule of the East India Company, the coast districts of the Cape of Good Hope inhabited by blacks and rebellious-spirited Dutch settlers; a few trading stations on the coast of west Africa, the rock of Gibraltar, the island of Malta, Jamaica, a few minor slave-labour

possessions in the West Indies, British Guiana in South America, and, on the other side of the world, two dumps for convicts at Botany Bay in Australia and in Tasmania. Spain retained Cuba and a few settlements in the Philippine Islands. Portugal had in Africa some vestiges of her ancient claims. Holland had various islands and possessions in the East Indies and Dutch Guiana, and Denmark an island or so in the West Indies. France had one or two West India Islands and French Guiana. This seemed to be as much as the European powers needed, or were likely to acquire of the rest of the world. Only the East India Company showed any spirit of expansion.

While Europe was busy with the Napoleonic wars the East India Company, under a succession of governors-general, was playing much the same role in India that had been played before by Turkoman and such-like invaders from the north. And after the peace of Vienna it went on, levying its revenues, making wars, sending ambassadors to Asiatic powers, a quasi-independent state, a state, however, with a marked disposition to send wealth westward.

We cannot tell here in any detail how the British Company made its way to supremacy sometimes as the ally of this power, sometimes as that, and finally as the conqueror of all. Its power spread to Assam, Sind, Oudh. The map of India began to take on the outlines familiar to the English schoolboy of today, a patchwork of native states embraced and held together by the great provinces under direct British rule…

In 1859, following upon a serious mutiny of the native troops in India, this empire of the East India Company was annexed to the British crown. By an Act entitled ‘An Act for the Better Government of India’, the Governor-General became a Viceroy representing the Sovereign, and the place of the Company was taken by a Secretary of State for India responsible to the British Parliament. In 1877, Lord Beaconsfield, to complete the work, caused Queen Victoria to be proclaimed Empress of India.

Upon these extraordinary lines India and Britain are linked at the present time.

1

India is still the empire of the Great Mogul, but the Great Mogul has been replaced by the ‘crowned republic’ of Great Britain. India is an autocracy without an autocrat.

Its rule combines the disadvantage of absolute monarchy with the impersonality and irresponsibility of democratic officialdom. The Indian with a complaint to make has no visible monarch to go to; his emperor is a golden symbol; he must circulate pamphlets in England or inspire a question in the British House of Commons. The more occupied Parliament is with British affairs, the less attention India will receive, and the more she will be at the mercy of her small group of higher officials.

Apart from India, there was no great expansion of any European empire until the railways and the steamships were in effective action. A considerable school of political thinkers in Britain was disposed to regard overseas possessions as a source of weakness to the kingdom. The Australian settlements developed slowly until in 1842 the discovery of valuable copper mines, and in 1851 of gold, gave them a new importance. Improvements in transport were also making Australian wool an increasingly marketable commodity in Europe. Canada, too, was not remarkably progressive until 1849; it was troubled by dissensions between its French and British inhabitants, there were several serious revolts, and it was only in 1867 that a new constitution creating a Federal Dominion of Canada relieved its internal strains. It was the railway that altered the Canadian outlook. It enabled Canada, just as it enabled the United States, to expand westward, to market its corn and other produce in Europe, and in spite of its swift and extensive growth, to remain in language and sympathy and interests one community. The railway, the steamship and the telegraph cable were indeed changing all the conditions of colonial development.

Before 1840, English settlements had already begun in New Zealand, and a New Zealand Land Company had been formed to exploit the possibilities of the island. In 1840 New Zealand also was added to the colonial possessions of the British Crown.

Canada, as we have noted, was the first of the British possessions to respond richly to the new economic possibilities that the new methods of transport were opening. Presently the republics of South America, and particularly the Argentine Republic, began to feel in their cattle trade and coffee growing

the increased nearness of the European market. Hitherto the chief commodities that had attracted the European powers into unsettled and barbaric regions had been gold or other metals, spices, ivory or slaves. But in the latter quarter of the nineteenth century the increase of the European populations was obliging their governments to look abroad for staple foods; and the growth of scientific industrialism was creating a demand for new raw materials, fats and greases of every kind, rubber and other hitherto disregarded substances. It was plain that Great Britain and Holland and Portugal were reaping a great and growing commercial advantage from their very considerable control of tropical and subtropical products. After 1871 Germany, and presently France and later Italy, began to look for unannexed raw-material areas, or for Oriental countries capable of profitable modernization.

So began a fresh scramble all over the world, except in the American region where the Monroe Doctrine now barred such adventures, for politically unprotected lands.

Close to Europe was the continent of Africa, full of vaguely known possibilities. In 1850 it was a continent of black mystery; only Egypt and the coast were known. Here we have no space to tell the amazing story of the explorers and adventurers who first pierced the African darkness, and of the political agents, administrators, traders, settlers and scientific men who followed in their track. Wonderful races of men like the pygmies, strange beasts like the okapi, marvellous fruits and flowers and insects, terrible diseases, astounding scenery of forest and mountain, enormous inland seas and gigantic rivers and cascades were revealed; a whole new world. Even remains (at Zimbabwe) of some unrecorded and vanished civilization, the southward enterprise of an early people, were discovered. Into this new world came the Europeans, and found the rifle already there in the hands of the Arab slave-traders, and negro life in disorder.

By 1900, in half a century, all Africa was mapped, explored, estimated and divided between the European powers. Little heed was given to the welfare of the natives in this scramble. The Arab slaver was indeed curbed rather than expelled, but the greed for rubber, which was a wild product collected under

compulsion by the natives in the Belgian Congo, a greed exacerbated by the clash of inexperienced European administrators with the native population, led to horrible atrocities. No European power has perfectly clean hands in this matter.

We cannot tell here in any detail how Great Britain got possession of Egypt in 1883 and remained there in spite of the fact that Egypt was technically a part of the Turkish Empire, nor how nearly this scramble led to war between France and Great Britain in 1898, when a certain Colonel Marchand, crossing central Africa from the west coast, tried at Fashoda to seize the Upper Nile.

Nor can we tell how the British government first let the Boers, or Dutch settlers, of the Orange River district and the Transvaal set up independent republics in the inland parts of South Africa, and then repented and annexed the Transvaal Republic in 1877; nor how the Transvaal Boers fought for freedom and won it after the battle of Majuba Hill (1881). Majuba Hill was made to rankle in the memory of the English people by a persistent press campaign. A war with both republics broke out in 1899, a three years' war enormously costly to the British people, which ended at last in the surrender of the two republics.

Their period of subjugation was a brief one. In 1907, after the downfall of the imperialist government which had conquered them, the Liberals took the South African problem in hand, and these former republics became free and fairly willing associates with Cape Colony and Natal in a Confederation of all the states of South Africa as one self-governing republic under the British Crown.

In a quarter of a century the partition of Africa was completed. There remained unannexed three comparatively small countries: Liberia, a settlement of liberated negro slaves on the west coast; Morocco, under a Moslem sultan; and Abyssinia, a barbaric country, with an ancient and peculiar form of Christianity, which had successfully maintained its independence against Italy at the battle of Adowa in 1896.