A Short History of the World (9 page)

Read A Short History of the World Online

Authors: H. G. Wells

The Beginnings of Cultivation

We are still very ignorant about the beginnings of cultivation and settlement in the world although a vast amount of research and speculation has been given to these matters in the last fifty years. All that we can say with any confidence at present is that somewhen about 15,000 and 12,000

BC

while the Azilian people were in the south of Spain and while the remnants of the earlier hunters were drifting northward and eastward, somewhere in North Africa or Western Asia or in that great Mediterranean valley that is now submerged under the waters of the Mediterranean sea, there were people who, age by age, were working out two vitally important things: they were beginning cultivation and they were domesticating animals. They were also beginning to make, in addition to the chipped implements of their hunter forebears, implements of polished stone. They had discovered the possibility of basketwork and roughly woven textiles of plant fibre, and they were beginning to make a rudely modelled pottery.

They were entering upon a new phase in human culture, the Neolithic phase (New Stone Age) as distinguished from the Palaeolithic (Old Stone) phase

1

of the Cro-Magnards, the Grimaldi people, the Azilians and their like.

*

Slowly these Neolithic people spread over the warmer parts of the world; and the arts they had mastered, the plants and animals they had learnt to

use, spread by imitation and acquisition even more widely than they did. By 10,000

BC

, most of mankind was at the Neolithic level.

2

Now the ploughing of land, the sowing of seed, the reaping of harvest, threshing and grinding, may seem the most obviously reasonable steps to a modern mind just as to a modern mind it is a commonplace that the world is round. What else could you do? people will ask. What else can it be? But to the primitive man of 20,000 years ago neither of the systems of action and reasoning that seem so sure and manifest to us today were at all obvious. He felt his way to effectual practice through a multitude of trials and misconceptions, with fantastic and unnecessary elaborations and false interpretations at every turn. Somewhere in the Mediterranean region, wheat grew wild; and man may have learnt to pound and then grind up its seeds for food long before he learnt to sow. He reaped before he sowed.

And it is a very remarkable thing that throughout the world wherever there is sowing and harvesting there is still traceable the vestiges of a strong primitive association of the idea of sowing with the idea of a blood sacrifice, and primarily of the sacrifice of a human being. The study of the original entanglement of these two things is a profoundly attractive one to the curious mind; the interested reader will find it very fully developed in that monumental work, Sir J. G. Frazer's

Golden Bough

.

3

It was an entanglement, we must remember, in the childish, dreaming, myth-making primitive mind; no reasoned process will explain it. But in that world of 12,000 to 20,000 years ago, it would seem that whenever seed time came round to the Neolithic peoples there was a human sacrifice. And it was not the sacrifice of any mean or outcast person; it was the sacrifice usually of a chosen youth or maiden, a youth more often who was treated with profound deference and even worship up to the moment of his immolation. He was a sort of sacrificial god-king, and all the details of his killing had become a ritual directed by the old, knowing men and sanctioned by the accumulated usage of ages.

At first primitive men, with only a very rough idea of the seasons, must have found great difficulty in determining when

was the propitious moment for the seed-time sacrifice and the sowing. There is some reason for supposing that there was an early stage in human experience when men had no idea of a year. The first chronology was in lunar months; it is supposed that the years of the biblical patriarchs are really moons, and the Babylonian calendar shows distinct traces of an attempt to reckon seed time by taking thirteen lunar months to see it round. This lunar influence upon the calendar reaches down to our own days. If usage did not dull our sense of its strangeness we should think it a very remarkable thing indeed that the Christian Church does not commemorate the Crucifixion and Resurrection of Christ on the proper anniversaries but on dates that vary year by year with the phases of the moon.

It may be doubted whether the first agriculturalists made any observation of the stars. It is more likely that stars were first observed by migratory herdsmen, who found them a convenient mark of direction. But once their use in determining seasons was realized, their importance to agriculture became very great. The seed-time sacrifice was linked up with the southing or northing of some prominent star. A myth and worship of that star was for primitive man an almost inevitable consequence.

It is easy to see how important the man of knowledge and experience, the man who knew about the blood sacrifice and the stars, became in this early Neolithic world.

The fear of uncleanness and pollution, and the methods of cleansing that were advisable, constituted another source of power for the knowledgeable men and women. For there have always been witches as well as wizards, and priestesses as well as priests. The early priest was really not so much a religious man as a man of applied science. His science was generally empirical and often bad; he kept it secret from the generality of men very jealously; but that does not alter the fact that his primary function was knowledge and that his primary use was a practical use.

Twelve or fifteen thousand years ago, in all the warm and fairly well-watered parts of the old world these Neolithic human communities, with their class and tradition of priests and priestesses and their cultivated fields and their development of villages

and little walled cities, were spreading. Age by age a drift and exchange of ideas went on between these communities. Elliot Smith and Rivers

4

have used the term âHeliolithic culture' for the culture of these first agricultural peoples. âHeliolithic' (Sun and Stone) is not perhaps the best possible word to use for this, but until scientific men give us a better one we shall have to use it. Originating somewhere in the Mediterranean and western Asiatic area, it spread age by age eastward and from island to island across the Pacific until it may even have reached America and mingled with the more primitive ways of living of the Mongoloid immigrants coming down from the North.

Wherever the brownish people with the Heliolithic culture went they took with them all or most of a certain group of curious ideas and practices. Some of them are such queer ideas that they call for the explanation of the mental expert. They made pyramids and great mounds, and set up great circles of big stones, perhaps to facilitate the astronomical observation of the priests; they made mummies of some or all of their dead; they tattooed and circumcised; they had the old custom, known as the âcouvade', of sending the

father

to bed and rest when a child was born, and they had as a luck symbol the well-known swastika.

If we were to make a map of the world with dots to show how far these grouped practices have left their traces, we should make a belt along the temperate and sub-tropical coasts of the world from Stonehenge and Spain across the world to Mexico and Peru. But Africa below the equator, north-central Europe and north Asia would show none of these dottings; there lived races who were developing along practically independent lines.

Primitive Neolithic Civilizations

About 10,000

BC

the geography of the world was very similar in its general outline to that of the world today. It is probable that by that time the great barrier across the Straits of Gibraltar that had hitherto banked back the ocean waters from the Mediterranean valley had been eaten through, and that the Mediterranean was a sea following much the same coastlines as it does now. The Caspian Sea was probably still far more extensive than it is at present, and it may have been continuous with the Black Sea to the north of the Caucasus mountains. About this great central Asian sea lands that are now steppes and deserts were fertile and habitable. Generally it was a moister and more fertile world. European Russia was much more a land of swamp and lake than it is now, and there may still have been a land connexion between Asia and America at Behring Straits.

It would have been already possible at that time to have distinguished the main racial divisions of mankind as we know them today. Across the warm temperate regions of this rather warmer and better-wooded world, and along the coasts, stretched the brownish peoples of the Heliolithic culture, the ancestors of the bulk of the living inhabitants of the Mediterranean world, of the Berbers, the Egyptians and of much of the population of south and eastern Asia. This great race had of course a number of varieties. The Iberian or Mediterranean or ‘dark-white’ race of the Atlantic and Mediterranean coast, the ‘Hamitic’ peoples which include the Berbers and Egyptians, the Dravidians, the darker people of India, a multitude of east Indian people, many Polynesian races and the Maoris are all divisions of various value of this great main mass of humanity.

1

Its western varieties are whiter than its eastern. In the forests of central and northern Europe a more blond variety of men with blue eyes was becoming distinguishable, branching off from the main mass of brownish people, a variety which many people now speak of as the Nordic race. In the more open regions of north-eastern Asia was another differentiation of this brownish humanity in the direction of a type with more oblique eyes, high cheekbones, a yellowish skin and very straight black hair, the Mongolian peoples. In South Africa, Australia, in many tropical islands in the south of Asia were remains of the early negroid peoples. The central parts of Africa were already a region of racial intermixture. Nearly all the coloured races of Africa today seem to be blends of the brownish peoples of the north with a negroid substratum.

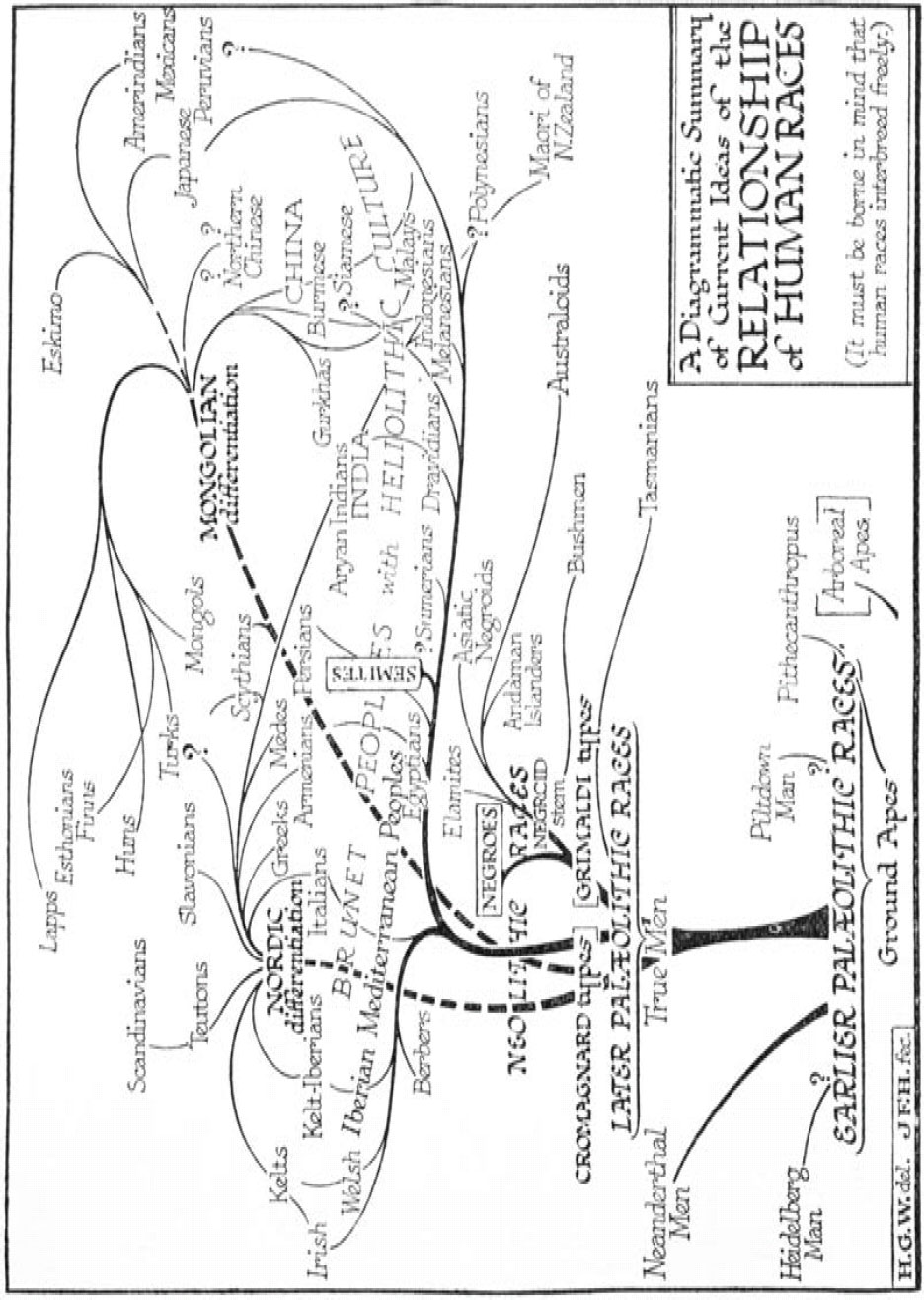

We have to remember that human races can all interbreed freely and that they separate, mingle and reunite as clouds do. Human races do not branch out like trees with branches that never come together again. It is a thing we need to bear constantly in mind, this remingling of races at any opportunity. It will save us from many cruel delusions and prejudices if we do so. People will use such a word as race in the loosest manner, and base the most preposterous generalizations upon it. They will speak of a ‘British’ race or of a ‘European’ race. But nearly all the European nations are confused mixtures of brownish, dark-white, white and Mongolian elements.

It was at the Neolithic phase of human development that peoples of the Mongolian breed first made their way into America. Apparently they came by way of Behring Straits and spread southward. They found caribou, the American reindeer, in the north and great herds of bison in the south. When they reached South America there were still living the Glyptodon, a gigantic armadillo, and the Megatherium, a monstrous clumsy sloth as high as an elephant. They probably exterminated the latter beast, which was as helpless as it was big.

The greater portion of these American tribes never rose above a hunting nomadic Neolithic life. They never discovered the use of iron, and their chief metal possessions were native gold and copper. But in Mexico, Yucatan and Peru conditions existed

favourable to settled cultivation, and here about 1000

BC

or so arose very interesting civilizations of a parallel but different type from the old-world civilization. Like the much earlier primitive civilizations of the old world these communities displayed a great development of human sacrifice about the processes of seed time and harvest; but while in the old world, as we shall see, these primary ideas were ultimately mitigated, complicated and overlaid by others, in America they developed and were elaborated to a very high degree of intensity. These American civilized countries were essentially priest-ruled religious countries; their war chiefs and rulers were under a rigorous rule of law and omen.

These priests carried astronomical science to a high level of accuracy. They knew their year better than the Babylonians of whom we shall presently tell. In Yucatan they had a kind of writing, the Maya writing, of the most curious and elaborate character. So far as we have been able to decipher it, it was used mainly for keeping the exact and complicated calendars upon which the priests expended their intelligence. The art of the Maya civilization came to a climax about

AD

700 or 800. The sculptured work of these people amazes the modern observer by its great plastic power and its frequent beauty, and perplexes him by a grotesqueness and by a sort of insane conventionality and intricacy outside the circle of his ideas. There is nothing quite like it in the old world. The nearest approach, and that is a remote one, is found in archaic Indian carvings. Everywhere there are woven feathers and serpents twine in and out. Many Maya inscriptions resemble a certain sort of elaborate drawing made by lunatics in European asylums, more than any other old-world work. It is as if the Maya mind had developed upon a different line from the old-world mind, had a different twist to its ideas, was not, by old-world standards, a rational mind at all.

This linking of these aberrant American civilizations to the idea of a general mental aberration finds support in their extraordinary obsession by the shedding of human blood. The Mexican civilization in particular ran blood; it offered thousands of human victims yearly. The cutting open of living victims,

the tearing out of the still beating heart, was an act that dominated the minds and lives of these strange priesthoods. The public life, the national festivities all turned on this fantastically horrible act.

The ordinary existence of the common people in these communities was very like the ordinary existence of any other barbaric peasantry. Their pottery, weaving and dyeing was very good. The Maya writing was not only carven on stone but written and painted upon skins and the like. The European and American museums contain many enigmatical Maya manuscripts of which at present little has been deciphered except the dates. In Peru there were beginnings of a similar writing but they were superseded by a method of keeping records by knotting cords. A similar method of cord mnemonics was in use in China thousands of years ago.

In the old world before 4000 or 5000

BC

, that is to say three or four thousand years earlier, there were primitive civilizations not unlike these American civilizations; civilizations based upon a temple, having a vast quantity of blood sacrifices and with an intensely astronomical priesthood. But in the old world the primitive civilizations reacted upon one another and developed towards the conditions of our own world. In America these primitive civilizations never progressed beyond this primitive stage. Each of them was in a little world of its own. Mexico, it seems, knew little or nothing of Peru, until the Europeans came to America. The potato which was the principal food stuff in Peru was unknown in Mexico.

Age by age these peoples lived and marvelled at their gods and made their sacrifices and died. Maya art rose to high levels of decorative beauty. Men made love and tribes made war. Drought and plenty, pestilence and health, followed one another. The priests elaborated their calendar and their sacrificial ritual through long centuries, but made little progress in other directions.