A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush (13 page)

Read A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush Online

Authors: Eric Newby

The valley was full of magnificent horses, the joint property of the people in the

aylaq

and some Pathan nomads, still higher up. Now, terrified, they went thundering away in single file, weaving through the maze of channels and up on to the mountain-side, manes streaming in the breeze.

This meadow was succeeded by a second in which the Pathan nomads were camped in black goatskin tents, an altogether fiercer, tougher bunch than the Tajiks and more mobile.

The third and highest had the same beautiful grass, and the same labyrinth of watercourses. At the far end, by the foot of a

moraine

that poured down into the meadow in a petrified cascade of stone, there was a large rock, covered with orange lichen, which offered some slight shade from the heat of the sun. Here we unloaded our horses. In the chronicles of any well-conducted expedition this would have been called the ‘base camp’.

All through the afternoon we lay close in under the rock, our heads and shoulders in shadow, the rest of our bodies baking in the sun. In the intervals of dozing we studied the mountain through Hugh’s massive telescope, which he normally carried slung in a leather case and which gave him a certain period flavour. From where we were at the foot of the

moraine

that ended a hundred yards away, it was obvious that there was a lot of what the military call, often with only too great a regard for accuracy, ‘dead ground’ between ourselves and the actual base of the

mountain. We were in fact in almost the same position as we had been on the

Milestone Buttress

: at the ‘start’ but not at the ‘beginning’.

What I could see was awe-inspiring enough. Mir Samir, seen from the west, was a triangle with a sheer face. It was obvious, even to someone as ignorant as I was, that at such an altitude not even the men whose kit reposed in the ‘

Everest Room

’ back in Caernarvonshire would be able to make much of the western wall. The same objections seemed to apply to a sheer gable-end directly facing us, which we had already christened with that deadly nomenclature that has a death-grip on mountaineers, the

North-West Buttress.

More possible seemed another more distant ridge of the mountain that appeared to lead to the summit from a more easterly direction.

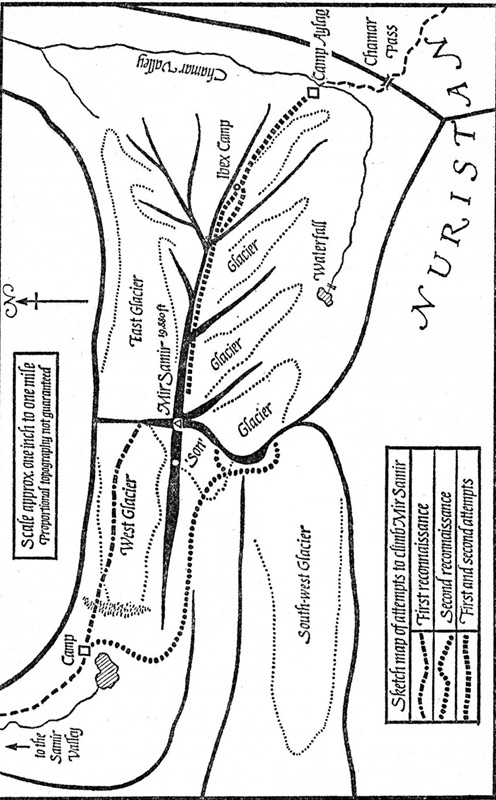

‘That’s our great hope,’ Hugh said. ‘You can’t see it from here but out of sight under the buttress there’s a glacier running down from a rock wall that joins up with the buttress itself. That’s the west glacier. This

moraine

comes from it.’ He indicated the labyrinth in front of us. ‘On the other side of the wall is the east glacier under the east ridge. My idea is to get up on the wall and either down on to the east glacier or round the edge of the buttress and up on to the ridge that way. It’s difficult to explain when you can’t see it,’ he added.

‘It’s impossible.’

What I

could

see was a continuous jagged ridge like a wall running from Mir Samir itself directly across our front and curling round to form the head of the valley.

‘

Pesar ha ye Mir Samir

, the sons of Mir Samir,’ was how Abdul Rahim picturesquely described the outriders of this formidable rock. He had promised to accompany us to the high part the next morning, though not to climb. Now he started to talk as any squire might of the hunting and shooting.

‘When I was a young man I could run through the snow as fast as an ibex and caught three with my bare hands. The winter, when the snow is deep, is the best; then the partridge and the ibex are driven into the valleys and with dogs and men we can drive them against a rock wall or into the drifts. But now I am old [he was thirty-two] and have grey hairs in my beard and sometimes my heart hurts like a needle. I have been many things. I was two years a soldier and when there was the uprising of the Safis I fought against them.’

3

He went on to tell us about his married life. ‘I have had three wives. The first two were barren but the third had three children. They were suffocated because she slept on them each in turn. She is a heavy woman. I would like to take another but they cost 9,000 Afghanis [at the official rate of exchange 50 to the pound about £150 in our money; at the bazaar rate of 150, about £50]. That is in money. In kind, two horses, five cows and forty sheep. After the wedding perhaps three hundred people come for a whole week of feasting. They must be given rice; so you see it is not cheap.’

It was time for the evening prayer and the four men made their devotions, orientated, I thought, rather inaccurately, towards Mecca.

‘I expect Abdul Ghiyas will be saying a few extra ones this evening,’ Hugh said as the ceremony, moving in its simplicity, came to an end. ‘I’ve asked him to come with us as far as the rock wall tomorrow.’

For the first time I noticed that planted in the meadow in front of Abdul Ghiyas where he had been saying his prayers was an ice-axe.

As the sun went down, the wind began to blow, dark clouds formed behind the mountain and the whole west face was bathed

in a ghastly yellow light that in the southern oceans would be the presager of a great gale. The heat of the day had rendered the mountain remote, almost unreal; now suddenly the air was bitterly cold and I tried to imagine what it could be like up there on the summit at this moment. We issued the windproof suits. Shir Muhammad rejected his, as did Badar Khan and Abdul Rahim; only Abdul Ghiyas accepted one.

The sun was setting behind the Khawak Pass. At this time I should have been leaving Grosvenor Street after a day under the chandeliers. Instead we were cooking up some rather nasty tinned steak over a fire that was producing more smoke than heat. The smell of burning dung, the moaning of the wind, the restless horses, the thought of Abdul Ghiyas saying his prayers, dedicating his ice-axe, and above all the mountain itself with its summit now covered in swirling black cloud, all combined to remind me that this was Central Asia. I had wanted it and I had got it.

When it was quite dark the noises began.

‘Ibex,’ said Hugh.

‘I think it’s damn great rockfalls.’

‘In the spring a panther took three lambs from this place,’ said Abdul Rahim.

‘Brr.’

We got up at four and huddled grey and drawn over a miserable fire of dung and the miracle root,

buta,

at this hour not readily combustible, and which never got going. The arrival of two barefooted Pathans, one wearing nothing but a shirt and cotton trousers, the other an ancient tottery man of eighty, a walking rag-bag, did nothing to make us feel warmer. Abdul Ghiyas was a fantastic sight in a rather mucky turban he had slept in all night, a windproof suit in the original war department camouflage and unlaced Italian climbing boots. He no longer looked like a nurse, more like a mad sergeant.

After drinking filthy tea and eating some stewed fruit, we set off, leaving Badar Khan to look after the horses. It would be tedious to enumerate the equipment we took with us; it was much the same as anyone else would have taken in similar circumstances: there was certainly less of it than any other expedition I have ever heard of. Each of us carried about forty pounds, all except Shir Muhammad who had a large white sheet with all the ropes and ironmongery in it slung across his shoulder. In the grey light we looked for all the world as though we were setting off for an exhumation. Even our ice-axes looked more like picks. I wished Hyde-Clarke could have seen us now.

‘I wonder what the Royal Geographical Society would think of this lot?’ said Hugh, as we splashed through some swampy ground in ‘Indian file’.

‘Doesn’t matter what they think, does it? We’re not costing them anything.’

‘They’ve lent us an altimeter.’

‘It’s nice to think they’ve got an interest in the expedition.’

Beyond the meadow that wetted our feet nicely for the rest of the day, we reached the

moraine,

grey glacial debris up which we picked our way gingerly. Above us the long ridges were already brilliant in the rising sun. We were three quarters of an hour to the head of the

moraine.

Here we rested. Abdul Ghiyas had a splitting headache brought on by the altitude; his face was ash-grey.

By seven the sun was blinding on the snow peaks. We were off the

moraine

now and on sticky mud where the torrents spilled over the edge of the plateau. Higher up, in the pockets of earth between the rocks, Abdul Rahim showed us fresh tracks of ibex and wolf. Then, suddenly, there was a terrific fluttering as birds got up in front of us and Abdul Rahim was off, dropping his rucksack, his

chapan

looped up, running like a stag at over 15,000 feet and disappearing over the edge of the hill.

There was an interval, then he reappeared half a mile away. Originally there had been five birds; now there were only two but he was on the trail of one flying ten yards ahead of him, going towards a lake which it splashed into. Whether he wanted to or not his impetus carried him into the water in a flurry of spray and he scooped the bird up.

Very soon he came loping towards us, the bird under his arm.

‘

Kauk i darri

,’ ‘I’m going to tame it,’ he said. It was a white snow cock, half grown. It seemed completely unafraid, nestling close to him. It was a remarkable achievement, particularly for one who had only the night before been telling us that he suffered from a weak heart.

Shir Muhammad chose this moment to unsling his sheet full of ironmongery and drop it with a great clang on the stony ground. Like a child out shopping with its mother, bored with the conversation over the baskets, he too was fed-up with standing around at 15,000 feet doing nothing in particular;

kauk i darri

taken by any means were commonplace to him. His action settled our camping place. It was as suitable as any other.

Round 1

We were in an impressive and beautiful situation on a rocky plateau. It was too high for grass, there was very little earth and the place was littered with boulders, but the whole plateau was covered with a thick carpet of mauve primulas. There were countless thousands of them, delicate flowers on thick green stems. Before us was the brilliant green lake, a quarter of a mile long, and in the shallows and in the streams that spilled over from it the primulas grew in clumps and perfect circles.

The lake water came from the glacier of which Hugh had spoken; we were in fact in the ‘dead ground’ that I had been trying hard to visualize during our telescope reconnaissance. From the rock wall that was our immediate destination, the glacier rolled down towards us from the east (to be accurate

E.N.E

.) like a tidal wave, stopping short a mile from where we were in a confusion of

moraine

rocks thrown up by its own movement, like gigantic shingle thrown up by the sea.

The cliff at the head which divided it, according to Hugh, from a similar larger glacier flowing down in the opposite direction, looked at this distance, about two miles, like the Great Wall of

China; while above it, like a colossal peak in the Dolomites but based at a far higher altitude, the mountain itself zoomed straight up into the air to its first bastion, the pinnacle of the north-west buttress. Above the buttress there was a dip, then a second ridge climbing to another pinnacle, twin to the first, then another ridge that seemed to lead to the summit itself.

The cliff joined the buttress low down on its sheer face. Vast slopes of snow or ice (in my untutored state there was no way of knowing the difference) reached high up its sides. To more skilful operators they might have offered an easy beginning; no one could have found the rock above anything but daunting.

For some time we considered our task in silence.

‘It’s nothing but a rock climb, really.’

‘I can see that.’

‘Just a question of technique.’

‘What I don’t see is, how do we get on to it.’

‘That’s what we’ve got to find out.’

The west wall that had filled me with such awe when the sun set on it was now scarcely to be seen at all; only the apex of that fearful triangle was visible with a light powder of snow on it, far less than I had imagined.

The lower part was obscured by

pesar ha ye Mir Samir

, ‘one of the sons’, a mountain loosely chained to the parent at a great height, 18,000 feet high, rising from the pediment of snow slopes above the glacier and running parallel with it across our front. From the valley it had seemed a continuous ridge but immediately beyond the lake it broke in a gap a mile wide, then rose again but not to the same heights. Between these two ridges there seemed to be the entrance to a deep valley, the far side rising in a fiendish-looking unscalable ridge, serrated with sharp pinnacles, like a mouth full of filed teeth.

Hugh was full of excitement.

‘That’s the way to the foot of the west wall.’

‘That’s the place I was hit on the head by a great stone with Carless

Seb

.’ This from Abdul Ghiyas who was looking extremely unwell; I was not feeling so good myself, having now rejoined Hugh in his troubles; inheritance of the deadly drinking habits we had cultivated in the Panjshir.

We set up our little tent. It was impossible to drive in pegs, there was too little earth. They simply folded up on themselves; instead we used boulders. With its sewn-in ground sheet and storm-proof doors it was like an oven. From it we emerged dripping with perspiration.

Abdul Rahim and Shir Muhammad now withdrew, having first bade us farewell in their different ways. There were tears in Abdul Rahim’s eyes as he clasped our hands. I was as deeply affected as he was. I respected his judgement in mountain matters and this demonstration of emotion I took as a confession that he did not expect to see us again. Nothing could shake that man of iron, Shir Muhammad; he set off down the mountain without a word and without a backward glance. He was negotiating with one of the Pathan nomads to buy a lamb and was anxious to resume business.

It was half past seven; already the day seemed to have lasted unduly long. Hugh was already laying out the gear.

‘The sooner we get to the top, the sooner we can leave; this is no place to linger,’ he said.

For once I agreed with him. Before we left I slipped behind a rock (no remarkable thing now that both of us were doing this anything up to a dozen times a day) and quickly studied the section of the pamphlet on the ascent of glaciers. It was rather like last-minute revision while waiting for the doors of the examination room to open, and equally futile.

We set off at a quarter to eight. All three of us were now dressed alike in windproof suits, Italian boots and dark goggles. On our heads we wore our own personal headgear. It was essential to wear something as the heat of the sun was already terrific. Our faces were smeared with glacial cream and our lips with a strange-tasting pink unguent of Austrian manufacture. We looked like head-hunters.

At first the way led over solid rock which shone like lead, polished by the friction of thousands of tons of ice passing over it. It was only a surface colour; chipped, it showed lighter underneath, like the rest of the mountain, a sort of unstable granite. To the left was another lake, smaller than the lower one but more beautiful, the water bright blue, rippled by the wind, inviting us to abandon this folly. At last we reached the terminal

moraine

, the rock brought down by the glacier now locked across the foot of it in confusion. It was as if a band of giants had been playing cards with slabs of rock, leaving them heaped sixty feet high. Through this mess we picked our way like ants. From the depths of the

moraine

came the whirring of hidden streams. Above us the ‘Son of Mir Samir’ towered into the sky, and from its fastnesses came unidentifiable tumbling sounds.

At eight-thirty we reached the glacier, the first I had ever been on in my life. It was about a mile and a half long. The ice was covered at this, the shallow end, by about a foot of snow, frozen hard during the night but now melting rapidly. The water was spurting out of the foot of the glacier as if from a series of hosepipes.

We embarked on it, keeping close in under the snow slopes which rose sheer to the mountain on the right hand; now in the cold shadow of the ‘son’ we put on our crampons. Apart from the day in Milan when I had bought them in a hurry, it was the first time I had worn crampons. I didn’t dare ask Hugh whether he had, but I noticed that his too were new.

‘I do not wish to continue,’ said Abdul Ghiyas, courageously voicing my own thoughts at this moment. It was obvious that he had never worn crampons from the difficulty he was having in adjusting them. ‘My head is very bad.’

‘My stomach is bad; the feet of Newby

Seb

are bad, yet we shall continue,’ said Hugh.

Cruelly, we encouraged him to go on. Perhaps it was the effect of altitude that made us do so. At any rate we roped up and he allowed himself to be linked between us without demur.

We set off; Abdul Ghiyas with his awful head, Hugh with his stomach, myself with my feet and my stomach. Apart from these ills, we all agreed that we felt splendid, at least we could feel our legs moving.

‘I think we’ve acclimatized splendidly,’ said Hugh with satisfaction. I found it difficult to imagine the condition and state of mind of someone who had acclimatized badly.

We moved up the glacier, plodding along with the unaccustomed crampons laced to our boots, clockwork figures, desiccated by the sun, our attention concentrated on the surface immediately ahead which we carefully probed with ice-axes for crevasses. All the time I had the feeling that our behaviour was ludicrous. Perhaps a more experienced party would have looked at the glacier and decided that there were none, at any rate as low down as this. But in the absence of any qualified person to ask it seemed better to continue as we were.

The light was very trying; even with goggles it was like driving into someone else’s headlights. We were thirsty and all around us was running water. It was difficult to resist the temptation to scoop up a mouthful but the state of our insides was sufficient warning for us not to do so.

Now the angle of the glacier increased as we began to climb towards the head. Here the snow was deep and I began to cut

steps. At first unnecessarily large but, as I got better, smaller ones. The rock wall was looming up now above us but running round the head of the glacier between us and the wall was something that looked like an anti-tank ditch.

‘

Bergschrund

,’ said Hugh.

‘What’s that?’

‘A sort of crevasse. This one’s only five feet deep.’

‘How do you know?’ We were in a rather unsuitable place for a prolonged discussion.

‘The year I was with Dreesen I slipped coming down and fell in it.’

‘Did you have crampons?’

‘No. Get on.’

I went on, marvelling. Even with crampons it seemed difficult enough but, of course, we were all wearing rubber soles. With nails it would have been more feasible; but then Hugh had not been wearing nailed boots in 1952 either.

Slowly we gained height until we were close under the overhang of the rock wall which was in cold shadow with great slivers of ice reaching down to impale us. Here the

bergschrund

gave out and we crossed it and began to traverse across the top of it on snow that was so hard and shiny as to be almost ice. It was impossible to see into the

bergschrund

; only the opening was visible. For all I knew it might have been a hundred and fifty feet deep.

Traversing this steep slope was far more difficult than the direct ascent we had been making up to now. For the novice crampons are both a blessing and a disaster and I was continually catching the points in my opposite trouser leg. For some time we had been belaying and moving in pitches in the correct manner taught us by the Doctor.

Finally at ten-thirty we hauled ourselves wearily up a few feet of easy rock and on to the top of the wall. We had only been

travelling for two hours but at this altitude it was sufficient for mountaineers of our calibre. At this point the wall was about fifteen feet wide; below us to the east it fell away in a sheer drop of two hundred feet to the head of the other glacier, the twin of the one we had just ascended. It was a much larger twin, tumbling away to the east in an immense field of white. Above it the north face of the east ridge swept up 3,000 feet from the glacier in fearful snow slopes, like something out of the pamphlet illustrating the dangers of avalanche, with overhangs of black rock and a really deep-looking

bergschrund

high up, under them.

‘What about

rappelling

down on to it?’ said Hugh.

‘How do you propose to get back if we do?’

‘It would be difficult,’ he admitted.

Somewhere above us was the summit but it was invisible, masked by the north-west buttress, smooth and unclimbable from the point where it was joined by the wall we were perched on. The wall itself was crowned with pinnacles of rock thirty feet high; at this moment we were in a dip between two of them.

Far away beyond the east glacier and a labyrinth of lesser mountains was a great mass of peaks, all snow-covered; one of them like an upturned cornet.

‘That’s Point 5953, the one we’re going to climb if we have time after this one,’ Hugh said.

1

The whole thing was on such a vast scale; I felt a pigmy, powerless.

‘Just what I thought,’ Hugh said. ‘It just confirms what Dreesen and I decided last time. Too much for us.’

I smothered an overwhelming impulse to ask him why we had come this far to find out something he already knew, but it was no place for irony; besides, the view was magnificent.

‘I’d like to see the other side of that ridge,’ he went on, indicating the east ridge. ‘If we fail on this side we’ll try it, there’ll be less snow.’

‘But more rock.’

‘It’s only three days’ march. We’ve got to go there in any case. It’s the way into Nuristan.’

The retreat began. I was end man. The feeling of relief that I experienced when I knew that we were to go no farther, coupled with the belief that the

bergschrund

was only five feet deep, had induced in me a light-headed sense of freedom from care; what the Americans call euphoria, a state of mind not consonant with my present responsibilities. It was no place for playing about. The snow was as hard as ice; none of us knew how to make an ice-axe belay on such a surface.

It was all right when I was controlling Abdul Ghiyas’s descent. He was behaving splendidly anyway and, probably from an innate appreciation of what to do in such a situation, he was handling the tools with which he had been issued admirably. It was only when I was descending myself that I felt irresponsible. Twice I caught my crampons in my trousers and slipped, giggling, fortunately in places where the snow was deep and soft.

Finally Abdul Ghiyas shouted to Hugh, who immediately halted. ‘He says you’re trying to kill us all,’ he bellowed up at me. ‘Are you mad?’