A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush (23 page)

Read A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush Online

Authors: Eric Newby

It also gives an impressionistic picture of life some fifty years ago in two adjacent but quite different valleys of the Hindu Kush (Indian Killer) range; a range named after the captives taken on the plains of India who perished while crossing the passes on their way to the slave markets of Central Asia. In addition, the book has a brilliant ending which describes our chance encounter with Thesiger, a historic figure from the golden age of exploration.

The second reason must lie in the train of catastrophic events, once barely imaginable, which have projected Afghanistan on to the world stage during the last four decades. In the 1960s, when mass tourism began to gather pace, the country had acted as a peaceful staging post for many thousands of young people on the overland route to India. But the 1970s witnessed a republican revolution which slithered into communism and Soviet occupation, thus turning Afghanistan into a battle ground of the Cold War. In the wake of the Russian withdrawal came an ethnic civil war, the rise of the mainly Pushtun Taliban, the emergence of al-Qa’eda and 9/11/2001. Today, NATO forces have for some years been engaged there in the struggle against militant Islamists. These events have all helped to maintain the rise in status of an already merit-worthy book.

When

A Short Walk

was published in 1958 it was well received, particularly by other writers. Evelyn Waugh agreed to write his perceptive foreword while Peter Fleming invited Eric and me to dine with him and Ella Maillart, the Swiss sportswoman and writer who had travelled with him from China to India in 1935.

The continuing success of the book was to bring us other invitations. In the early 1970s Cooks, the travel agency, asked us to lead the first trekking tour for mountain walkers in Afghanistan. They were already running such tours successfully in Nepal. It

was to begin and end at Bamian in the central highlands and go up the beautiful Ajar valley where the river was said to be brimming with trout. But then a famine was reported and this was followed by the republican coup when King Zaher was deposed. Cooks abandoned the project.

In the late 1990s we were to have returned to Afghanistan to make a film for BBC television. The difficulty was that the Taleban controlled most of the country. However, we could fly on a UN plane to Faizabad in Badakhshan in the north-east where Merlin, the British medical charity,

7

had a team of doctors and nurses. The founder and then director of Merlin, Dr Christopher Besse, even offered to come with the Newbys and me as our personal physician. But in summer 1998 the Taleban recaptured Mazar-i Sharif, the main town in the north, and slaughtered many of its inhabitants. The BBC decided that the project would be too difficult and too dangerous.

8

Thus, our hopes of returning to Afghanistan together were twice frustrated by events.

Looking back on our journey into the Hindu Kush in 1956 my reflections centre on the good fortune we enjoyed.

9

Afghanistan was then cocooned in a rare period of peace and stability which lasted for some forty years until roughly 1973. This allowed our small expedition to go forward without let or hindrance. We got on well with our three sturdy Tajik companions, who spoke the Persian dialect now known as Dari; and we were glad to have with us as a guide and counsellor their leader Abdul Ghiyas. He seemed to have friends everywhere. One of them was Abdul Rahim, who caught the young snowcock at 16,000 feet near the foot of Mir Samir.

Abdul Ghiyas had a certain discipline. Say we agreed with him the need to make an early start the next day: he would be up by three, have said his early prayers, lit a fire and boiled water for

the tea by three thirty when he would rouse us. The horses would then be loaded and by four he would have the show on the road. This was a magic hour. The valleys would remain in deep shadow while the rays of the eastern sun cast their light around the topmost peaks. For a time the air would remain cool and still but by eight or nine o’clock both men and horses would be ready for a halt. Abdul Ghiyas would then preside over making the tea. He would fashion a fireplace with a few stones, Shir Muhammad would provide dried horse dung and the rest of us would bring the dead roots and branches of artemisia, the low sage brush, which grew widely. Then the comedy would begin.

We would all gather round, longing impatiently for the first restoring sips of tea. Someone would enquire: ‘Ao jush mikonad, Abdul Ghiyas?’ (‘Is the water boiling?’). A moment later another would venture: ‘Mijushad?’ (‘Is it boiling?’). The answer to such cheek might be the favourite Afghan expression for the negative: a forward tilt of the chin together with a smack of the lips against the tongue. At last the water would be on the ‘jush’, Abdul Ghiyas would then reach into his capacious waistcoat, extract a pouch of tea, tip a small measure onto the palm of one hand and pour it into our blackened kettle. Sugar, a luxury in the Panjshir, would be reserved for red-letter days.

Without the agreement of Abdul Ghiyas, we would have never been able to cross the Chomar Pass into Nuristan. He could, without much exaggeration, have claimed that the road was impossible for horses. The others would have supported him. Even with his acquiescence, it was with some anxiety that we followed the barely visible track leading up to and over the pass into the Ramgul valley. Would we find a land of milk and honey or disturb a hornets’ nest?

Of course we found neither. The isolated Ramgul was a world apart from the well-trodden Panjshir. Its inhabitants spoke an ancient language called Kati, favoured homespun clothing, and

were intensely suspicious of strangers, whether Afghan or other. This was hardly surprising as it was only within living memory that they had been subdued and forcibly converted to Islam by the Amir Abdul Rahman. One of the questions they plied us with was whether we were Nikolai? This must have been a reference to contacts which they had had formerly with traders from Tsarist Russia, possibly dealers who had sold them rifles.

We were fascinated to visit the Ramgul, a valley of Nuristan which had remained little known to the outside world. Had we failed to get there, this would have compounded our other failure, through inexperience, to reach the summit of Mir Samir.

10

As it was, when we crossed the Arayu pass back into the friendly Panjshir, we felt some admiration for the rugged Nuristani way of life but also relief that no serious mishap had befallen us.

When Soviet forces occupied Afghanistan in the 1980s, the Panjshir valley became one of the leading centres of resistance. Under their legendary leader, Ahmad Shah Masud, the Tajiks withstood numerous attacks by the Red Army and today rusting Soviet tanks remain there as evidence. Later, this resistance spread to neighbouring provinces. It was sustained, at least in some part, by the export of lapis lazuli from the famous mine at Sar-i Sang in Badakhshan. The lapis was carried by caravans of pack horses across Nuristan to Chitral and the outside world. The horses returned with supplies.

11

The Soviet withdrawal was followed by a civil war in which ethnic ambitions were at times supported by foreign interests. In the mid-1990s, the Pushtun Taleban slowly extended their control over the main towns, only leaving a few corners of the country in the hands of the Northern Alliance (Tajiks, Uzbeks and Hazaras). But then came 9/11 with the United States tilting the balance of power against al-Qa’eda and the Taleban. Sadly, Masud

was assassinated by al-Qa’eda in 2001, but our three companions from 1956 managed to survive the wars. In 2007 Badar Khan, who lived at Jangalak, played a part in the BBC television film about Eric as a travel writer made by Icon films.

12

Two or three years ago I asked Eric which of the books he had written was his favourite. I had half expected him to reply that it was his first book,

The Last Grain Race

, which had been about his first great adventure and had also fostered the largest number of different editions; or perhaps

Love and War in the Apennines

, which has already appeared as an excellent film.

13

But he answered

A Short Walk

, and said that sometimes, when he felt depressed, he would open his copy and read either the first or the last chapter. And then, he added, he would feel much better. I sometimes feel the same.

HUGH CARLESS

AUGUST

2008

1.

Lascelles was British Ambassador to Ethiopia 1949–51, to Afghanistan 1953–57 and, as Sir Daniel, to Japan 1957–59.

2.

The

Moshulu

, a four-masted Finnish-registered barque, was one of the ten sailing vessels owned by Gustav Erikson of Mariehamn in the Aaland Islands which took part in the grain race from Australia to Europe in 1939.

Moshulu

, laden with Australian wheat, won in the time of ninety-one days. The language used on board was Swedish.

3.

6 RSF, 15 (Scottish) Division.

4.

Wanda Newby wrote an engaging account of her early life in Slovenia, then a province of Italy, and her wartime years near Parma in

War and Peace: Growing up in Fascist Italy

(London, Collins, 1991). Marrying Eric in 1946, she lived with him happily for over sixty years.

5.

Eric Newby,

A Traveller’s Life

(London, Collins, 1992).

6.

Tony Davies,

When the Moon Rises

(London, Leo Cooper, 1973). Davies made a remarkable attempt at escape, walking seven hundred kilometres down the crest of the Apennines for three months until he was shot in the foot and recaptured

on the Sangro river. After the war he qualified in medicine and practised as a much-admired family doctor in the Tillingbourne valley in Surrey.

7.

In 2008 Merlin still maintain medical staff in Badakhshan and Takhar, where they specialize in helping the Afghan authorities to reduce maternal mortality.

8.

The film would have been produced by Peter Firstbrook and directed by Amanda Theunissen.

9.

In 2007, The Royal Society for Asian Affairs invited me to give a lecture on ‘Eric Newby, The Hindu Kush and The Ganges’ which was later published in

Asian Affairs

, vol. XXXVIII, no. III, November 2007.

10.

In 1959, a group of German climbers from Nuremberg claimed the honour of having been the first to scale Mir Samir. They had evidently bivouacked nearer the summit than we had dared to do, and so had been able to get up and down the following day.

11.

Sandy Gall was the leading British journalist to report, by television films and also by his books, on the resistance led by Masud. In addition, in 1983 he founded Sandy Gall’s Afghanistan Appeal as a charity to provide orthopaedic equipment and workshops for disabled Afghans.

12.

The Icon film

Travellers’ Century: Eric Newby

(TX 2008 BBC4) was directed by Harry Marshall and filmed by Benedict Allen.

13.

Hallmark Hall of Fame television film

Love and War

2001.

My thanks are due to the Afghan Government for their kindness and co-operation in allowing me to travel in Nuristan, and to

Vogue

for permission to reproduce

Meeting an Explorer

which first appeared in it and which is now incorporated in Chapter 20.

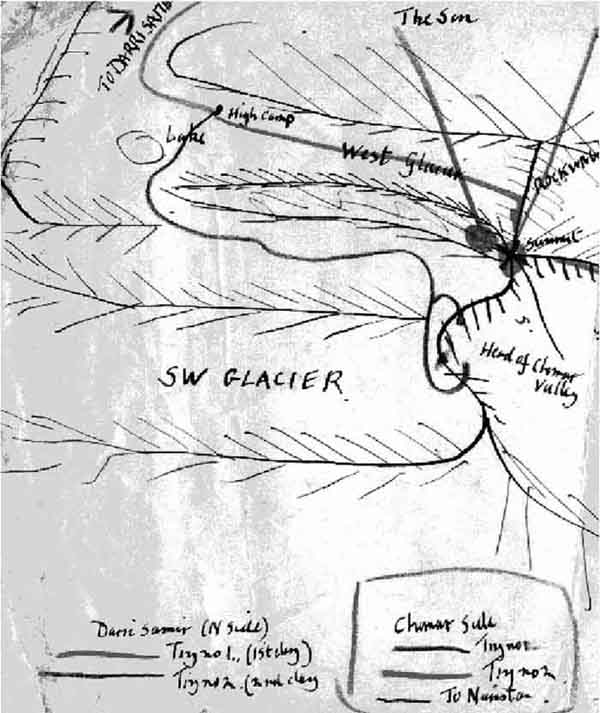

The map to illustrate the journey is based on the maps of the Survey of India and a traverse made by Wilfred Thesiger,

D.S.O.

, in 1956, and our own researches.

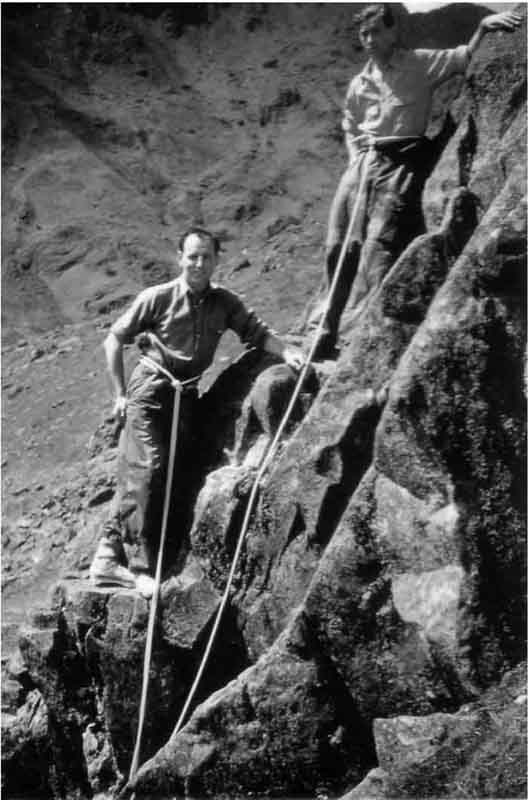

Novices on the Milestone Buttress, Snowdonia, May 1956.

Page from the author’s manuscript: Mir Samir.

Hugh Carless in the pilgrims’ photo booth; Meshed, Iran.

Camp on the ibex trail: hard lying on shattered rock.

On Mir Samir, a steep pitch.

Crossing the Chamar Pass; Shir Muhammad with the chestnut and Badar (Bahādar) Khan with his white.

Eric with some of the elders in Pushal. Second from the right is the ‘company promoter’.

Younger men in Pushal.

Stone houses with timber frames, Ramgul Valley.

The Ramgul Valley looking south towards Lake Mundul.

The proud owner of a prize fighting partridge in the Ramgul.

Wilfred Thesiger at sunup, Panjshir Valley.

Portrait of two failures.

Novices on the Milestone Buttress, Snowdonia, May 1956.