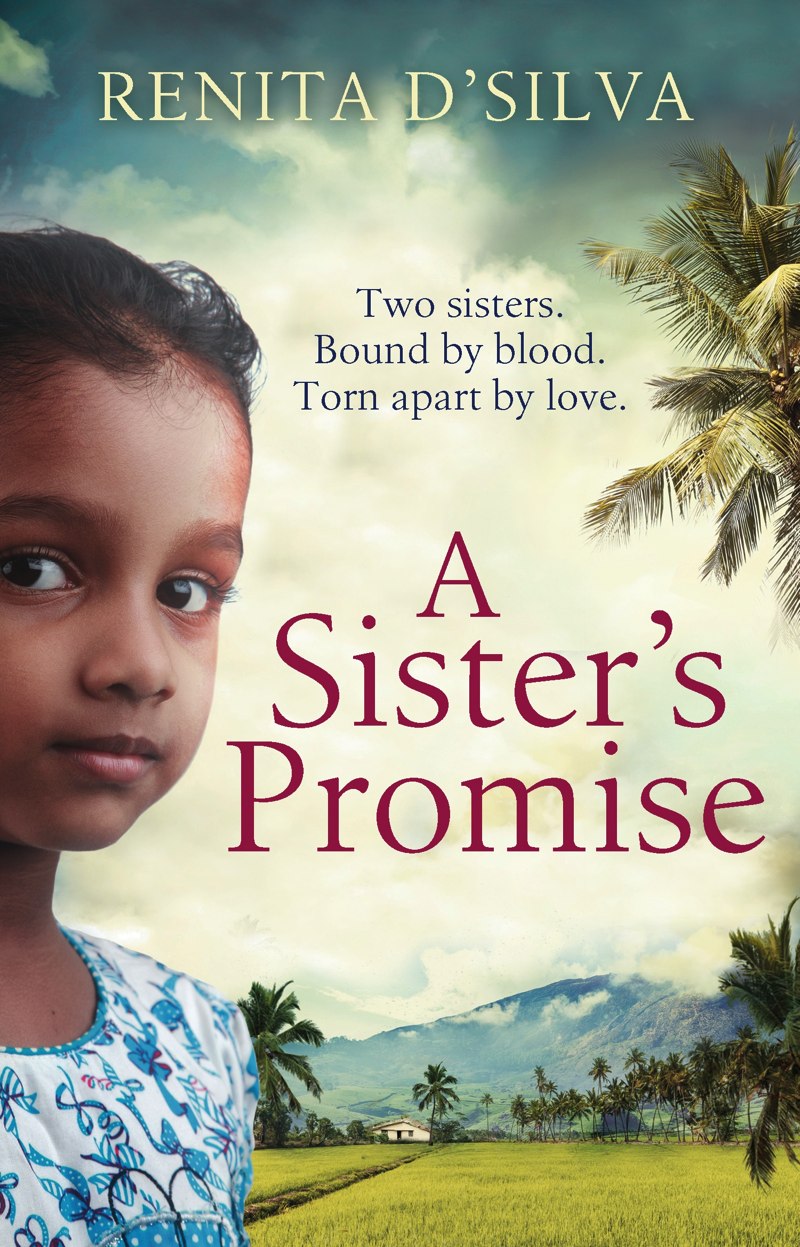

A Sister's Promise

Read A Sister's Promise Online

Authors: Renita D'Silva

A SISTER’S PROMISE

RENITA D’SILVA

In memory of my grandfather, Simon Rodrigues, Aba, (1918 - 2002) – the vanquisher of pythons; the nemesis of cockroaches, spiders and sundry bugs; the herald of our achievements; soft voiced and big hearted, protector and provider.

And in memory of my grandmother, Mary Rodrigues, Ba, (1929 - 2015) – the repository of anecdotes and old wives’ tales, gossip and ghost stories and recipes; the dispenser of advice and wisdom; the owner of magic hands that healed and fed, cooked and created. Loved.

PROLOGUE

BENEDICTIONS FROM A BENEVOLENT GOD

Two girls frolic on a summer’s evening, and while shadows slant grey in emerald fields, they revel in the golden taste of happiness, basking in the warm radiance of childhood, innocence and freedom.

Touch-me-nots, their blooms, the soft, sugar-embroidered pink of a happy ending, shrink from the kiss of grumbling yellow bees. Butterflies coyly flutter their emerald-tipped silver wings as if dispensing benedictions from a benevolent god. High up in the coconut trees, the crows squabble and gossip.

The taller girl, pigtails swaying in the fragranced breeze, closes her eyes and counts. The smaller girl hides among the copse of trees at the edge of the field as the lone cow, tail twitching, keeps watch and envelops her in its mildly curious, liquid mahogany gaze.

‘Here I come,’ shouts the seeker and she darts among the fields, her churidar ballooning around her.

The other girl peeks from behind the base of the mango tree as she breathes in the tart green smell of ripening mangoes, her hands attuning to the knobbly brown feel of bark.

‘Got you,’ the taller girl yells, coming up behind her, but the smaller girl screams as she slips on the moss at the base of the tree, her knee exploding in a spurt of red as she cuts it on a sharp-edged stone.

The taller girl holds the smaller one in her arms and gently wipes away the blood oozing through the torn churidar bottoms.

The cow strains at the rope that tethers it to the post and comes up to them, nudging their faces with its soft wet nose: the slimy feel of fish guts, the earthy tang of manure.

The girls laugh, syrup and sweetness, their angst forgotten, dispersed into the evening air that brings cooking smells wafting up to them. The cow bellows, a long, mournful moo.

‘Here,’ says the taller girl, rubbing at the blood that still sprouts in scarlet droplets from the wounded girl’s knee. ‘Let’s make a promise to love and look out for each other forever.’

The wounded girl hesitates for one protracted beat during which the other girl’s smile slips.

Then, she too dips her pinkie finger in the blood and ignoring the summons to dinner that carry over the gurgling of the stream, and drift across the fields, they link their fingers together and recite, ‘We will always look out for each other and love each other best.’

KUSHI

THE GHOST OF DARING TO DREAM TOO BIG

BHOOMIHALLI, INDIA

In my fevered dreams, in this peculiar half-awake state, I see myself writing the letter.

The seemingly innocuous wad of papers penned in meticulous joined-up letters, in my best handwriting, and my mother’s voice echoing in my ears: ‘Remember, for some people, your handwriting is their first, and perhaps only, introduction to you.’ My brain fired up, vivid images of amber flames dancing in front of my eyes, my ink-marked fingers working zealously.

Now, my agitated mind whispers a warning from the confines of this strange bed in which I find myself strapped; medicinal sheets swaddle me in a claustrophobic embrace, as I watch my younger, naive self making copies, penning addresses, sealing envelopes.

I am unable to do any more than gag on the bitter taste of glue, damp paper and remonstrance, my hollow stomach dipping, knowing that it is done and in the past. My words posted and in the relevant hands, set into action events which will culminate in the here and now: this delirious state; this bizarre prison.

The letter then:

To:

The Chief Minister of Karnataka

CC: The Minister for Higher Education; The Minister for Law, Justice and Human Rights.

Dear Sirs,

My name is Kushi Shankar. I am seventeen years old and a resident of Bhoomihalli village. I am writing this letter to you because, in my opinion, even though you have been elected to represent the people of this state and have pledged to do your best by them, you sometimes forget how they, i.e. we, the common people, live.

Mr Chief Minister, I know that you grew up in the city, started your political career there and now reside there in a huge mansion in the poshest part of the city. I am not faulting you for this. I just wonder if you know what it is really like for the people in the villages, that’s all. The people you are supposed to protect and look after, whose concerns, you assure us, are your priority.

Well, we don’t feel that way here in Bhoomihalli and I am sure this is the case in other villages as well. We feel let down, disillusioned. You promise us all these things so we vote for you: clean roads, drinking water, medical facilities, a good education and then you renege on these promises as soon as you are elected. Is this fair?

Why do we have to suffer power cuts every single evening and through the night while your city mansions have electricity day in and day out? Why do we still not have the medical facility that has been promised us by every politician before every election since my father was a boy, and have to travel to Dhoompur to get medical help and medicines? Why do we have to queue for hours at the one communal tap every summer when our wells dry up, for water the colour of sludge that comes for one hour each day, at different and entirely random times? Where are the borewells you have promised us? Where is the clean, running water?

All of these concerns I have raised here are important, of course, but they are not the real reason I am writing to you. I have a specific purpose in writing this letter, which I will tell you about in a minute. But mostly, this letter is a plea, showing you how it is for us and asking you to please do something.

Now, I am going to present to you a scenario.

Picture this:

The Engineering College on the outskirts of Dhoompur. The one with the imposing gate and the leafy, tree-lined drive leading up to the formidable two-storey building, with its cement roof and its tall gables; with its chattering, confident students who wear their sense of entitlement like an extra set of clothes. The one whose glossy prospectus promises 100% placement at the end of the four-year course, a white-collar job guaranteed.

Every child in Bhoomihalli and the neighbouring villages seeks admission into the hallowed portals of this college, dreaming of being one of the revered students with their poise and their absolute belief in a sunny future. The parents of Bhoomihalli’s aspiring children are farm labourers who work so very hard to make sure their kids get the education they themselves were denied, which is why they perform back-breaking labour in other men’s fields for little return.

These farmers would like their children to be officers, to wear shirts and trousers, not lungis and holey vests. They would like their children to carry briefcases spilling over with documents—which they, mere labourers, cannot read—and not bricks and rubble, or yokes and bales of hay. They would like their children to have an upright bearing, not a back permanently bent with lugging the cares of the world. They would like their children’s skin to be pampered and soothed by the air-conditioned interior of offices, not burnt to a crisp by the unforgiving sun.

They would like their children to speak the English of the educated, not the Kannada and Tulu of the masses. They would like their children to have soft, well-fed bellies sagging contentedly over their belts, not concave stomachs that ache with hunger and struggle to hold up lungis like their own.

They would like their children to eat meat at least three times a week, not once every few months when the cow that was their livelihood finally gives up on life and has to be butchered, the paltry, stringy meat clinging to the bones tasting of worry. For how will they replace Nandini, who was so very loyal and gave milk every single day even though she lived only on a diet of scorched, yellow grass?

And the villagers can conceive of only one way that their children can have all of this, and that is through education, that magic word that promises entry into the echelons of the rich and the well settled.

At the local school which the children of these labourers attend, the teachers change like the weather, they appear and disappear like apparitions, like gods who every once in a while give a darshan to favoured supplicants. When the teachers disappear—they are not paid enough, they say, and go to the cities in search of better recompense and the big break they know is their due—there is no choice but to club two or three classes together, no matter the pupils’ ages. These range from eleven to fifteen, with some of the older children stepping in to teach the younger ones. Is it any matter then that there is such a disparate success rate between schools in the city and those in the villages?

The teachers who do stay more than a month or two all recite the same mantra, unintentionally echoing the message that is drilled into the village children by their parents so many times that they know it by heart: Study hard, bag a seat at the Engineering College, get out of here.

And so, the children of the labourers study and their parents work extra-long hours to procure the requisite textbooks. As the exams loom, the villagers forgo meals for a week or two to send their children for tuition in Dhoompur, to centres that claim ‘Sure-fire Success in Pre-University and CET Exams’.

And these village kids, who lack textbooks and teachers and classroom space, pass the exams with flying colours, their high ranks in the CET assured to win them entry into the Engineering College. They are invited to the city to choose their seat, their shiny, assured future gleaming tantalisingly before them.

On paper, of course, that is what is supposed to happen.

But does it?

Now my ma says that it was a different system while she was growing up. In those days you chose the schools you wanted by post. You sent off the form and either you were offered a place or you weren’t. So, the travesty I am about to narrate was much easier to execute then and not as transparent, you see.

Anyway, the surprising thing is that my ma, yes, you heard right, was offered a place to study medicine at Hosahanapur College! This is because she won the first rank in the entire state and the education board couldn’t in all honestly refuse her a place at the college of her choice. She, after all, had first claim on any or all of the seats. If they had refused, it would have caused too big a furore to sweep under their scandal-studded carpet.

Now, back to my scenario. To make this easier, I am going to narrate it from the point of view of Somu, the boy who scored the top marks in the entire village last year.

Somu and his da arrive in the city to choose a place at the Engineering College. Somu shakes the grime off his clothes as best he can, and pats his hair down using the dust-smeared, cracked glass of the groaning, overstuffed city bus window as a mirror, as he and his da journey to the interview hall. His father stands beside him, too close due to the press of commuters. Both of them are uncomfortable in the shiny new clothes purchased for this day from money obtained by emptying the rainy day fund. Somu’s father is desperately missing his lungi and tries to discreetly adjust his crotch which feels confined and trapped inside the unfamiliar trousers.