A Train in Winter (24 page)

Authors: Caroline Moorehead

However much was delivered—and there were weeks when nothing at all arrived from the women’s families—food became, and remained, an obsession. Some women had stomach cramps from hunger and few had much energy. One day Marie-Claude fainted from hunger. Betty took to speaking of a ‘community of corpses’. So bad did the hunger become that Danielle, who had once again appointed herself the leader of the women, arranged for all the prisoners whose windows gave on to the street to throw them open at the same time and to shout out together: ‘J’ai faim! J’ai faim! J’ai faim!’ Outside the fort, passers-by paused and listened. After this, though Danielle and Germaine Pican, perceived as the two ringleaders of the group, spent several days without food in one of the damp, dark punishment cells, Trappe agreed to put a ladle in the watery gruel and taste it, and as a result the soup became a little richer. ‘It taught us an important lesson’ Germaine would later say. ‘It made us understand that we were not completely powerless.’

To her family, Marie-Claude wrote—on scraps of paper, the writing so small that it could barely be read without a magnifying glass, the letter smuggled out of Romainville by the Breton cooks in exchange for money—that the women’s teeth were rotting from lack of calcium. ‘There are among us friends who are visibly shrinking,’ she added, saying that she dreaded the thought of the approaching winter on one bowl of soup a day. ‘I dream about beans, lentils, noodles, potatoes and cream puddings.’

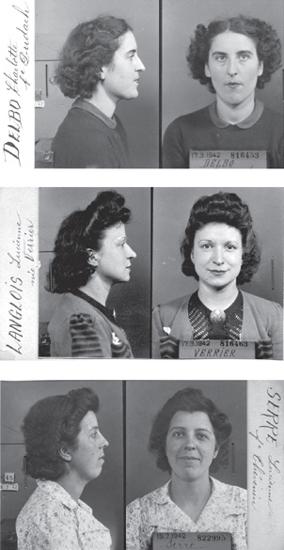

Danielle, who kept all discouragement at bay with her constant good humour and determination, told her mother, in another smuggled letter, that she had never looked more elegant, having shed some more of her pre-war extra kilos. Her old friends, she wrote, would never recognise her now, so slender had she become. Cécile would later say that it was not nearly as hard for her as for the other women, because she had so often been hungry as a child. When a photographer came to Romainville on the orders of the Gestapo to take the women’s photographs, 17-year-old Simone was the only one who looked healthy and well fed, though in some of the pictures the women could be seen smiling, their friends having pulled faces and giggled as the photographs were being taken.

Simone Sampaix

Photographs of Charlotte, Betty and Lulu taken in Romainville

When she found a way to get a letter out of the fort, Annette Epaud, proprietor of L’Ancre Colonial in La Rochelle, wrote to her family that she was suffering from spells of terrible depression. ‘It’s very hard to be separated from those you love. I hope this ends quickly… I miss my Claude so much.’ She added that those women who had no news at all of their families felt very miserable and isolated, particularly those who, like Maï and Lulu, had left small children behind. Annette suggested that her sister bake a cake and send it to her with a letter hidden in the middle, and if possible also a pair of shoes. To Claude she wrote: ‘Little Claude, always be good and nice. And always love your mother’.

Under the firm hand of the older women, the female section was soon very busy. Maï, who had been a midwife, organised gymnastics and cold showers every morning, saying that the women needed to be fit to face whatever awaited them. Families were asked to send in wool, sewing materials and old clothes, which the women unpicked and turned into sweaters and bags.

As in La Santé, a news bulletin—the information gleaned from listening to the guards, to the Breton cooks and to any news brought in by new arrivals—was put together in the dormitory occupied by Danielle, Charlotte and several of the other women who had once been part of the

résistance intellectuelle

. Marie-Claude spoke good German, which helped. Written in blue methylene stolen from the infirmary on the brown wrapping paper of the Red Cross parcels, the

Patriote de Romainville

was copied out and handed around the dormitories, to be destroyed at the end of each day when it had been read by everyone. Its tone was upbeat. The news was good: the Germans were under assault in the east, and the Allies were advancing in North Africa. There was every reason to hope that the war would soon be over. The

Patriote

also listed complaints about the meagre ration of soup, the lack of fat and sugar, the prohibition on letters. It was a measure of Danielle’s ferocious will, and of Josée’s and Marie-Claude’s organisational skills, that no one was allowed to sink into a state of depression and apathy. The two women instilled in the others a sense of pride, a resolve not to be beaten, which spread round the dormitories and held them together.

Day by day, the friendships between the women deepened. Cécile arrived in Romainville distinctly wary of those who, like Danielle and Marie-Claude, seemed so assured and knowing. As she saw it, her communist credentials were no less good than theirs, but their education and their class seemed impossibly superior to her own. She felt nervous, ill at ease. Meeting Charlotte on the stairs every day, wrapped in a voluminous cloak and fur hat given to her by Louis Jouvet and holding herself tall and upright, her face made up, having brought with her powder and lipstick, Cécile thought her arrogant and unfeeling. Each morning, with heavy irony, she gave a little bow and said: ‘Bonjour, madame.’ Charlotte did not reply. But then the day came when the two women began to laugh; and from then on they were inseparable. Charlotte’s laugh, said her friends, was particularly attractive.

All across the women’s section, in the dormitories, on the staircase, in the courtyard, other friendships were born and grew, women separated by age, schooling, class and profession drawn into patterns of affection and understanding by shared stories and similar losses. Grieving for their executed husbands, missing their children, fearful for their families, they talked, for there was not much else to do; and, as they talked, they felt stronger and better able to cope. Already they were conscious that the nature of women’s close friendships would shield them in the weeks to come, and that the men, on the other side of the fort, were often not bound to each other by similar ties. ‘We did not need to “make friends,”’ Madeleine would say, ‘we were solidly together already.’ ‘We were,’ Betty said, ‘a team.’

Those women who had husbands and lovers in the Resistance and still free were terrified that they might be caught; those whose men were already in the hands of the Gestapo, some of them in the hostage cells across the courtyard in Romainville, lived in a state of constant anguish: how soon might they be taken and shot as hostages for an attack on the Germans? Madeleine Normand, the farmer’s wife who had sold her animals to raise money for her clandestine life, one day caught sight of her husband in the courtyard: he could barely see her, because he had been almost blinded by torture.

Bonds of mutual fear and sorrow linked the women, from dormitory to dormitory. The two sisters, Lulu and Jeanne who had known Cécile in the Resistance, now grew closer to her; Charlotte became attached to Viva; Germaine grew fond of Danielle. Bit by bit, affection found expression in mutual help, in the remembering of birthdays, in anticipating needs and countering the bleakness with warmth. Many of the women were witty and they made each other laugh. A Spanish woman, Luz Martos, who had come to France after the defeat of the republicans, entertained the others by jumping up on to the table to demonstrate Spanish dances. At night, when it was very cold, the women slept close together, sharing blankets. Anniversaries of every kind were marked and celebrated in dozens of small ways. On 11 November, at midday, every woman stopped what she was doing and sang the Marseillaise in memory of the armistice of the First World War.

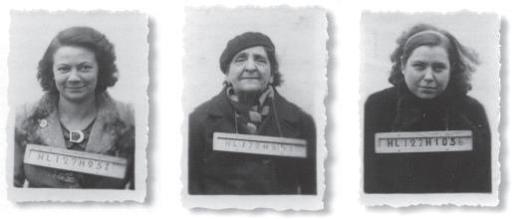

Suzanne Maillard, Maï Politzer, Marie-Elisa Nordmann

Olga Melin, Yvonne Noutari, Annette Epaud

Yvette Guillon, Pauline Pomies, Raymonde Georges

At first, there was also a not altogether comfortable political hierarchy. About half the women were communists, and it was the communists who felt that it had been they who had led the most effective life in the Underground. Whether as liaison officers such as Cécile and Betty, or writers and editors such as Maï and Hélène Solomon, or organisers such as Danielle, they remained highly conscious of the cause for which they had fought. ‘We don’t forget, even in prison, that we are communists,’ wrote Betty somewhat primly in a letter smuggled out soon after she reached Romainville. ‘Do you see,’ wrote Danielle, ‘they can kill us, but while we live they will never extinguish the flame that warms our hearts… It won’t be long before our country is again free, and the USSR wins.’ The early Resistance, as they saw it, had been directed largely by them, and they felt not only a sense of personal entitlement but a certain wariness towards those drawn in, either out of loyalty to a relation or simply out of distaste for the occupiers. Such women, they made it felt, lacked conviction.

One result of this political consciousness was that in the early days of Romainville a slight breeze of political purity wafted through the women’s section, intimidating to outsiders, who knew that they were being discreetly vetted before being drawn into the fold. Newcomers, without the same political commitment and often more easy-going and less well educated, found the inventive and unflagging determination of the communists daunting.