A Trial by Jury (8 page)

Authors: D. Graham Burnett

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Murder, #Jury, #Social Science, #Criminal Law, #True Crime, #Law Enforcement, #General, #Legal History, #Civil Procedure, #Political Science, #Law, #Criminology

Acting all of this out a few feet from the witness stand, directly in front of the jury box, the murder weapon in his hand, the prosecutor again and again swung the open knife, rolling his head and shoulders into each exaggerated stroke as he growlingly challenged the witness to deny that this, in fact, was how Cuffee met his death.

“And didn't you thenâlike this!âstab him? And thenâagain!âlike this? As he tried to crawl away? Andâagain!”

But the sensational dramatizationâwhich the judge refused to interrupt, and which sent the victim's family howling from the room as several of the jurors squirmed in disgustâbuilt to a crashingly flat climax.

To the blistering assertion that this was how it had happened, Milcray offered a simple answer.

“No.”

If anything was going to shake him, one thought, it would have been that.

So egregious did I find the whole performance that, as Milcray returned to his seatâslightly hunched, as if afraid of bumping his head on somethingâI felt a deep desire to see the prosecutor lose the case. How did that whisper of a thought affect what followed? It is difficult to say.

Sentiment aside, the prosecution's case left a crucial question unaddressed: motive. It is true that the law did not require proof of a motive (in a second-degree-murder trial, only intent to kill must be shown, not the motivation for doing so). But a sane individual, asked to find an apparently mild-mannered personâone with no history of violent crimeâguilty of a grotesquely cruel murder (twelve of the stab wounds fell in a small area in the back of the head), strongly wishes for at least a wisp of a rationale. When none can be offered, it is hard to resist entirely, as beyond doubt, a claim of self-defense.

On this matter the prosecution had very little. In summing up the state's case, the prosecutor again harped on a myriad of more and less grave inconsistencies in Milcray's defenseâthe changed stories, the implausible account of the many wounds to the back (how could they have been delivered while Cuffee was on top, given that they were all on the side

opposite

Milcray's knife hand?), the limited evidence of struggle in the small space (knickknacks still standing on the television, right next to a life-or-death thrash?)âand added to these some positively weird things that the prosecutor himself thought anomalous: for instance, why hadn't Cuffee and Milcray engaged in any foreplay before they began to disrobe? If, as Milcray testified, Cuffee's penis was flaccid when he first removed the panties, how could he have had an erection just moments later, when he turned back from putting on the condom? Such peeves told us more about the prosecutor's erotic universe (it seemed to me) than they did about Milcray's testimony. As for the concluding assertionâthat we were looking at “the face of evil” when we surveyed the defendantâit seemed patently false to me, whatever may have happened in that room that night.

Clearly there were very serious problems with Milcray's account(s). Much of what he had told us was not credible. Yet, for all that, the prosecution could offer distressingly little in response to that powerful lingering question: Why? The best that the state could do was to paint a picture of Milcray as a spurned lover, and as a man torn apart by the “inner demons” of his sexual double life. That night, the prosecutor intimated, Milcray had sat on the futon longing for more than a quick lay, but Antigua wanted to have sex and move on. (Remember, Nahteesha said Antigua was going to get rid of him!) Looking away as he put on the condom, Cuffee probably made some offhand remark, and something in Monte “snapped”âturning back, Cuffee found the knife ready-drawn, and barely had time to throw up his hands (he had a small cut on the web between the thumb and index finger of his right hand) in a futile effort to block the sudden surprise blow to the heart.

The key bits of evidence for this scenario? In addition to the ostensible difficulty of opening the knife (demanding that Milcray prepare for the stabbing while Cuffee was looking away), the prosecutor returned to the mysterious double condoms on the floor. According to his closing argument, the odd semen tests (yes on the penis, no on the condoms) showed that Cuffee had gotten the condoms

out

but had not yet put them

on

âhence, he was stabbed in the midst of doing so.

But there was an obvious problem with this. Both condoms were fully unrolled, with one inside the other, indicating either that they were at some point both on a penis, or that Cuffee put on condoms like no one else in the world. What was the prosecutor thinking?

The last defense witness was the partner of the police officer who had testified for the prosecution about initially finding the body. He was asked only one substantive question: Who kicked in the door at apartment one, 103 Corlears? He answered emphatically that he had. Unfortunately, his partner had earlier claimed the honor for himself, with equal certainty. It was a tiny point, but an oddly powerful one: Could we trust anyone who had given evidence on anything?

Â

I

ride down in the balky, crowded elevator. I have become obsessed with alibis and think, continually, about whether, if everything depended on it, I could establish my whereabouts at different moments in the past, the content of fleeting conversations, the minute chronologies of a day or an evening. Most of daily life, I am realizing, construed as evidence, looks flimsy, suspicious, improbable, lacking adequate corroboration.

When the door opens on the floor below the courtroom, the defense attorney steps in. We have been repeatedly warned by the judge to have no interactions with counsel for either side. I keep my eyes dead in front of me.

“Hey, Ed,” he says to someone in the back.

They strike up a conversation.

The defense attorney's new cocker-spaniel puppy has just been spayed.

“Yeah,” he says solemnly, shaking his head, “I have got

one sick puppy

at home.”

Out of the corner of my eye, I see him smile sympathetically.

Is he trying to influence me?

PART II

__________________

The Deliberations

5. Into the

Closed Room

T

hrough all of this, through more than ten days of testimony and evidence, I walk to the court in the morning, go home for lunch (which I eat alone, reading

The Economist

at a small round table in a sunny corner), walk home in the evening. This strolling to and from my daily work brings me a great deal of pleasure.

By varying my route, I meander through SoHo, TriBeCa, Little Italy, or Chinatown, watching the life in each neighborhood: the giant geoduck clams, glumly clamped on their outlandish siphons, sitting in Styrofoam crates at the fish wholesaler on Lafayette; the porn-and-stereo-supply stores ratcheting open their metal grates on Canal early each morning; the impossible beauties sashaying along lower Broadway in the evenings. One morning I pause to watch a garbage truck smolder on White Street, abandoned by its crew, the flames beginning to appear between its armor plates, the sirens whining their approach. One afternoon I am brought up short in front of a Chinese restaurant called the Canal Fun Corp. There, in the windowâin addition to the hanging ducks, their beaks charred, their necks question-marked by the wire roasting racksâsits a large clawed disk, like some grotesque crab. I look more closely: it is a pig's face, earless, and butterflied by the butcher in such a way that the split lower jaw spreads into two evil hemistichs of a smile.

Is this, I wonder, some sort of garnish?

These walks leave time for thought. We associate truth with knowledge, with seeing things fully and clearly, but it is more correct to say that access to truth always depends on a very precise admixture of knowledge and ignorance. This is nicely captured by the traditional figure of justice, a blindfolded woman holding a scale. With her balance she can assess certain things, with her eyes closed she cannot see certain other things. True justice depends as much on her blindness as on her ability to discern.

Where juries are concerned, the courts pay particular attention to ignorance: keeping the jury in the darkâabout certain pieces of evidence deemed inadmissible, about the procedural technicalities that constrain the activities of the court, about the most basic sense of what is to be expected in the unfolding of a trialâclearly constitutes an important aspect of judicial practice. I assume different judges take this strategy to different lengths; and the spectrum of serviceable ignorance extends from sublime safeguards (juries must not be told that they can, in fact, disregard the law, or “nullify,” with impunity) to considerably more prosaic obfuscation (refusing to tell a sequestered jury where they will be spending the night).

The judge of Part 24 liked his juries as out of it as possible. This became clear earlyâhe was terse and elliptical when he addressed us, and had obviously given the officers of the court instructions to answer few questions and, when obliged, to do so in the least precise wayâbut this approach was never more in evidence than when he handed the case over to us for deliberation. He gave us almost no direction at all as to how we were to conduct ourselves in the jury room, and he ran through the charges we were to consider very briskly, despite their complexity.

These can be summed up as follows. We could find Milcray guilty of murder in the second degree or, failing that, of a lesser charge, manslaughter. The primary distinction between these was the issue of intent. In order to find someone guilty of murder in the second degree, it must be shown that the accused both intended to kill and did so. To find someone guilty of manslaughter, by contrast, it need only be shown that the defendant acted “recklessly” and in doing so occasioned death. Intent, we were told, was a state of mind, and it was therefore “invisible.” How were we to make a decision about the state of the defendant's mind when we had been told that we were to constrain ourselves to the facts established by the evidence in the case, and were not to speculate or indulge in conjecture? Fear not: the law invited us to use our common sense to infer the state of the defendant's mind from whatever elements in the record lent themselves to such inferences. Another Gordian knot of philosophy cut nicely by the sword of justice: the inward states of other people were, in fact, accessible, for our purposes, by means of their outward actions. Next question.

This satisfying appeal to common sense, however, did not mean that we were beyond the realms of scholastic hairsplitting. For the prosecution wished us to consider the charge of second-degree murder under two different “theories”: the standard “intent” theory, and another, introduced to us as the “depraved indifference” theory. I tried to concentrate with all my power as the judge enlarged on the distinction.

In general, he told us, the law had evolved to treat killing someone intentionally as more blameworthy, more grievous, than doing so without intent. However, there were deemed to be certain situations in which a person's action or behavior was so egregious, so heinous, so unjustifiable, that this distinction did not hold. In other words, if someone showed a “depraved indifference to human life” that resulted in a homicide, it was considered just as blameworthy as if the killing had been intentional. If we found that Milcray had acted with “depraved indifference to human life,” then we were to disregard the issue of intent and find him guilty of murder in the second degree. If we could find no evidence of intent to kill but we did detect an indifference to human life that appeared to us no more than “reckless,” then he was guilty of manslaughter, the lesser charge.

These were fine distinctions, the sort that Thomistic quibblers love. It was a great deal to digest orally, in a single sitting, without a pencil.

Nor was that all. The defendant in this case, the judge explained, had introduced the issue of “justification.” Under New York State law, he went on, you can justifiably use deadly force if you reasonably believe that you are about to be the victim of a rape or a forcible sodomy (technical definition here: any part of the penis entering the mouth or anus). So, if we found that the defendant reasonably believed he was in imminent danger of such an assault, then actions he took that led to the death of the attacker could be justified; we were then to find the defendant not guilty.

Much of the first two days of our deliberations consisted of a sustained effort to understand the charges themselves, what they implied, and how we were to go about considering them. Some of this would have been easier if we had been able to see the judge's instructions, which he read aloud after the closing arguments. All we were given, however, was a sheet that listed the possible verdicts with key words for each: second-degree murder (intent); second-degree murder (depraved indifference); and manslaughter (reckless). We were also given a stack of ruled sheets for written communications with the court.

I say “we,” but it was I who was given these papers, immediately before we were directed to leave our seats and file past the bench into the jury room to begin deliberations. Eight days into the trial, our grandfatherly foreman, Richard Chorst, had failed to show up.

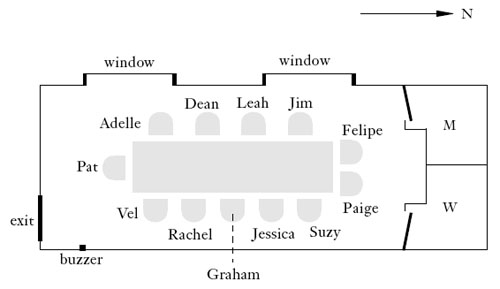

Initially this occasioned only irritation. We had several times been delayed by late juror appearances, which kept us milling around in the hallway. But Chorst had been quite correct in all ways, sitting up straight, his suits pressed, chatting politely in a reserved, friendly, Midwestern manner, his hands perennially folded in his lap. Then he vanished. As his tardiness stretched past the morning, the court clerk made a series of phone calls, checking Chorst's home and, it was rumored, local hospitals and precincts. But nothing turned up. Out in the hall word passed around that Chorst had mentioned to one of us that he had a long-planned trip abroad that was rapidly approaching. Had he just gone AWOL? The judge wanted to wait, so he sent us out on our lunch break early. When there had been no word by midafternoon, we were called into the court, and the judge moved me to the foreman's seat, on my right, calling up an alternate to take my old placeâLeah Tennent, the spirited young woman with the ready smile and global-village air. She seemed pleased and focused when she sat down next to me. It would have been very hard to have spent the weeks listening to the evidence only to be dismissed when the deliberations beganâthe fate of the three other alternates.

The judge made no real effort to explain to us what role the foreman was to play once the case was in our hands, and he never even made it clear if we were obliged to retain the foreman he appointed. In fact, the first thing I did upon our settling into the jury room (after proposing that we collect ourselves in several moments of silence) was to offer to cede my place to whomever we chose by a show of hands. At that early moment, when relief (that things were finally in our control) and excitement (something new!) were strong, people waved off the suggestion. It was clear several jurors thought that reaching a verdict was going to be a matter of minutes, so procedural questions seemed quaint, irrelevant.

I had sensed that there might be more resistance to my retaining the position. When I was originally placed in the foreman's seat, I rapidly revised my courtroom appearance. In place of roughneck urban wear, I began turning up in work clothes, the sort I would wear to the office: a tie, a sweater vest, a blazer. A few of the jurors remarked on the transformation, most in a cordial way, suggesting that perhaps I was trying now to fill the departed Chorst's well-polished shoes and keep up our collective jury dignity before the disagreeable judge. But Paige, the decorator with the downtown attitude, gave this an acid turn as we were waiting outside the courtroom.

“He thinks we are going to be impressed, and that this will help him lead us,” she quipped to a few others.

Well, yes, actually, I suppose, there was probably a bit of that. But a bit, too, of simple respect for the forms, and, after all, I had worn a tie practically every day since grammar school. It wasn't that I was putting on airs, but that I had, in a way, shown up initially in a vacation disguise. At the same time, Paige was responding to something more than my suede waistcoat: she could read my general affect among fellow jurors as what it was, a species of aloofness. Over the first two weeks of the trialâin the halls, the snack shop, at shared lunchesâmost of the jurors had cultivated a basic sociability. Generally I had not engaged with the others, but had sat alone and read. Later, I staked out a small abandoned desk at one end of the hall, and used it to work on the index to my book. Paige, I could sense, didn't like the “I sit apart” routine, the “I read poetry on this bench down here during break” routine.

I could see her point. Academics cultivate a certain pomposity, most of them; I doubtless reflected years in that world. The resulting behaviors probably didn't really come across as particularly significant to some other jurorsâto hardy Dean, say, the vacuum-cleaner repairman. Whether I read difficult modernist poems for fun in the hall appeared to be of no consequence to him. But Paige, as a décor person, had a sharp eye for styles and could scent the supercilious; she had seen college professors be jerks before. She was watching.

As a courtesy, I stepped out of my seat and let the others pass in front of me as we filed out of the box to leave the courtroom and begin deliberations. It was a formal gesture.