A World Lit Only by Fire (40 page)

Read A World Lit Only by Fire Online

Authors: William Manchester

That had been lèse majesté with a vengeance, and it had been swiftly punished. The angry sovereign had set a price on Pole’s

head; the cardinal had fled for his life, eluding capture but suffering nevertheless, for during his fugitive years both his

mother and brother were beheaded. Now, at his urging, Mary made her attempt to restore papal supremacy over England. The penal

laws against heresy were revived. On her orders, Archbishop Cranmer was burned at the stake—other famous martyrs were Bishops

Ridley and Latimer—and Pole was then consecrated in Canterbury as Cranmer’s successor. Over three hundred Englishmen, whose

only crime had been following Mary’s father out of the Roman Church, were also executed. Perhaps her most significant achievement,

which she shared with Henry, was her demonstration that England could be just as barbaric as the rest of sixteenth-century

Europe. Even today she is remembered as Bloody Mary.

T

HE IMMORTAL

Maid of Orleans still dominated memories of the prior century. But now the sixteenth was more than half gone and it had produced

no woman to match her; indeed, no heroines at all. Then, late in its sixth decade, irony intervened to produce a woman who

would rank with the greatest sovereigns in English history, giving her name to a new age which would redeem the squalor of

the old. She was the daughter of the disgraced Anne Boleyn, who had lain in Anne’s womb, awaiting birth, during the coronation

Sir Thomas More had ignored. On the day of her birth, she had been declared illegitimate by the Vatican. In the wake of her

mother’s execution the archbishop of Canterbury—after ruling that Anne had, in fact, been married to Percy at the time of

her royal wedding and had thus been bigamous as well as adulterous and incestuous—had concurred with Rome, pronouncing the

child a bastard.

Anne having been formally declared a common slut—thus placing her far beneath Catherine, whose status as a divorcée was

relatively respectable—the royal solicitors concluded that Henry’s second marriage had had no legal status whatever. Since

it had never occurred, the three-year-old waif who had been its only issue had no legal existence. Like her half-sister, however,

and indeed because of her, Anne’s daughter was to be rescued from oblivion. The restoration of Mary’s legitimacy created a

precedent. After Jane Seymour’s death in childbirth, Parliament, bowing to Henry’s will, recognized all three of his children,

conceived in various wombs, thus establishing the final order of Tudor succession: first Edward, son of Jane; then Mary, daughter

of Catherine; and finally, Elizabeth, daughter of Anne.

Crowned in 1558 at the age of twenty-five, Elizabeth I restored Protestantism, revived her father’s Act of Supremacy, and

reigned over England for forty-five glorious years. In light of the tragic consequences of her parents’ sexual excesses, which

had typified European nobility in their time—the promiscuity, the proliferation of bastards, the hasty coupling in palace

antechambers—she was perhaps wise to live out her long life unaccompanied by a connubial consort, and to be remembered in

history as the Virgin Queen.

ONE MAN ALONE

I

N THE TEEMING Spanish seaport of Sanlúcar de Barrameda it is Monday, September 19, 1519.

Capitán-General Ferdinand Magellan, newly created a Knight Commander of the Order of Santiago, is supervising the final victualing

of the five little vessels he means to lead around the globe:

San Antonio, Trinidad, Concepción, Victoria

, and

Santiago

. Here and in Seville, whence they sailed down the river Guadalquivir, Andalusians refer to them as

el flota

, or

el escuadra

: the fleet. However, their commander is a military man; to him they are an armada—officially, the Armada de Molucca. They

are a battered, shabby lot, far less imposing than the flota Christopher Columbus led from this port twenty-one years ago,

leaving Spain for his third crossing of the Atlantic.

Nevertheless the capitán-general’s armada is more seaworthy than it appears—he has seen to that. Now approaching his forties,

the man who will become the greatest of the sixteenth-century explorers is a precise, even fastidious mariner. Every plank

and rope has been personally tested by him; he has directed the replacement of all rotten timbers and overseen the installation

of new shrouds and new sails of strong new linen, each stamped with the cross of St. James, patron saint of Spain. Each of

the five requires a lot of looking after. The small ships—

San Antonio

, the largest, displaces only 120 tons—are actually

naos

, three-masted, square-rigged hybrid merchantmen derivative of fourteenth-century cogs and Arabian dhows. Unless carefully

attended, all are potential shipwrecks. Therefore they have been repeatedly scoured and caulked from stem to stern. Now their

grizzled commander is patiently checking the stores for a two-year expedition—never dreaming that the great voyage will

take three years, and that he will not survive it.

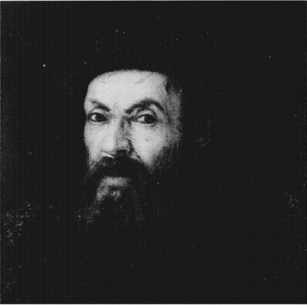

Physically Magellan is unimpressive. He was born to one of the lower orders of Portuguese nobility, but his physique is that

of a peasant—short, swart, with a low center of gravity. His skin is leathery, his black beard bushy, and his eyes large,

sad, and brooding. Long ago his nose was broken in some forgotten brawl. He bears scars of battle and walks with a pronounced

limp, the souvenir of a lance wound in Morocco. He had acted recklessly then (and will again, in the last hours of his life),

but he is rarely impulsive. On the contrary; his reserve approaches the stoical. He is a man who lives within, saving the

best of himself for himself, enjoying solitude. As a commander he can be ruthless—“tough, tough, tough,” in the words of

a fellow captain. Subordinate officers dislike this

dureza

, though they concede his supreme competence and the quickness with which he rewards those who perform well—rare traits

among commanders of the time. Because of this, he is popular among his crews.

Proud of his lineage, meticulous, fiercely ambitious, stubborn, driven, secretive, and iron-willed, the capitán-general, or

admiral, is possessed by an inner vision which he shares with no one. There is a hidden side to this seasoned skipper which

would astonish his men. He is imaginative, a dreamer; in a time of blackguards and brutes he believes in heroism. Romance

of that stripe is unfashionable in the sixteenth century, though it is not altogether dead. Young Magellan certainly knew

of El Cid, the eleventh-century hero Don Rodrigo, whose story was told in many medieval ballads, and he may have been captivated

by tales of King Arthur. Even if he had missed versions of Malory’s

Morte d’Arthur

, he would have been aware of Camelot; the myths of medieval chivalry had persisted for centuries, passed along from generation

to generation. Arthur himself was a genuine, if shadowy historical figure, a mighty English

Dux Bellorum

who won twelve terrible battles against Saxon invaders from Germany and was slain at Camlann in

A.D

. 539. Less real, but enchanting to children like the youthful Magellan, was the paladin Lancelot du Lac, introduced in 1170

by the French poet-troubadour Chrétien de Troyes. De Troyes was also celebrated for his

Perceval, ou Le Conte du Graal

, the first known version of the Holy Grail legend, which was retold in 1203 by the German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach as

the story of

Parzival

. Both De Troyes and Von Eschenbach were translated into other European languages, including Portuguese. And there were others.

At his death in 1210 Gottfried von Strassburg left his epic

Tristan und Isolde

. In 1225 France’s Guillaume de Lorris wrote the first part of the allegorical metrical romance

Roman de la Rose

, distantly based on Ovid’s

Ars Amatoria

. Chaucer translated it in the next century. And in 1370 or there-abouts

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

, a poetic parable of Arthur’s elegant nephew, appeared in England.

Magellan, a man of boundless curiosity, has found reality equally enthralling, devouring the works of Giovanni da Pian del

Carpini, who in 1245 had traveled east to Karakorum in central Asia, and Marco Polo’s account of his adventures in the Orient,

Ferdinand Magellan (c. 1480–1521)

dictated to a fellow prisoner in 1296. More important, the commander of the five little ships has been inspired by the feats

of Columbus and the discoverers since. Other Europeans have dreamed of following their lead. What sets Magellan apart is his

unswerving determination to match them and thus become a hero himself. Erasmus and his colleagues are admirable, but they

are writers and talkers; Magellan believes that deeds are supreme. He would agree with George Meredith—“It is a terrific

decree in life that they must act who would prevail”—and in his struggle for dominance his most valuable possession will

be his extraordinary will. He can endure disappointment and frustration, but can never accept defeat. He simply does not know

how.

Yet thus far his career has been one of unfulfilled promise. Although he craves recognition, his very directness—his complete

lack of guile, or even tact—has repeatedly cost him the support of those in a position to honor him. In Lisbon, for example,

he disdained the silken subtleties at the royal court, and, as a result, encountered disaster. To the urbane courtiers surrounding

the fatuous king, he seemed an awkward boor. Having suffered from a false accusation of larceny, and having then cleared his

name, he sought an audience with Dom Manuel I, the Portuguese sovereign. He wanted royal support for his great voyage. Both

Portugal and Spain coveted the Spice Islands; Magellan urged the king to help him stake Portugal’s claim there. But he had

handled the interview badly. Manuel, a fop, expected his subjects to fawn over him. Ignoring court protocol, Magellan went

straight to the point. His sovereign responded by dismissing him in the rudest possible manner, turning his royal back while

the courtiers tittered. His Majesty had even told the supplicant that the Portuguese crown had no further need for his services

—that he could take his proposal elsewhere. Magellan, single-mindedly pursuing his vision, then put himself at the disposal

of Spain’s eighteen-year-old King Carlos I, soon to become Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. On March 22, 1518, acting in his

own name and that of his insane mother Johanna, Carlos signed a formal

Yo el Rey

agreement, or

capitulación

, underwriting the capitán-general’s voyage and appointing him governor-to-be of all new lands to be discovered by the expedition.

Now Magellan moves from vessel to vessel, counting first the stores needed to feed the 265 members of his crews—quantities

of rice, beans, flour, garlic, onions, raisins, pipes and butts of wine (nearly 700 of them), anchovies (200 barrels), honey

(5,402 pounds), and pickled pork (nearly three tons); then the thousands of nets, harpoons, and fishhooks which will be needed

to supplement diets; next, astrolabes, hourglasses, and compasses for navigation; iron and stone shot for his cannon, and

thousands of lances, spikes, shields, helmets, and breastplates, should they land on hostile shores, as is likely; forty loads

of lumber, pitch, tar, beeswax, and oakum, hawsers, and anchors are insurance against shipwrecks; mirrors, bells, scissors,

bracelets, gaily colored kerchiefs, and brightly tinted glassware are intended to befriend natives in the East. … The inventory

goes on and on. It seems endless, but the admiral’s interest never flags.