A World Lost: A Novel (Port William) (19 page)

Read A World Lost: A Novel (Port William) Online

Authors: Wendell Berry

Now that I have told virtually all I know of the story of Uncle Andrew

and of his death and how we fared afterward, I see that I must return to

my old question - What manner of man was he? - and make peace with

it, for I am by no means certain of the answer. A story, I see, is not a life.

A story must follow a line; the telling must begin and end. A life, on the

contrary, would be impossible to fix in time, for it does not begin within

itself, and it does not end.

Within limits we can know. Within somewhat wider limits we can

imagine. We can extend compassion to the limit of imagination. We can

love, it seems, beyond imagining. But how little we can understand!

Whatever he was, Uncle Andrew was more than I know. In drawing

him toward me again after so long a time, I seem to have summoned, not

into view or into thought, but just within the outmost reach of love,

Uncle Andrew in the plenitude of his being -the man he would have

been for my sake, and for love of us all, had he been capable. In recalling

him as I knew him in mortal time, I have felt his presence as a living soul.

However we may miss and mourn the dead, we really give little deference to death. "Death," a friend of mine said as he approached it himself, "is a convention ... not binding upon anyone but the keepers of

graveyard records." The dead remain in thought as much alive as they

ever were, and yet increased in stature and grown remarkably near. The

older I have got and the better acquainted among the dead, the plainer it

has become to me that I live in the company of immortals.

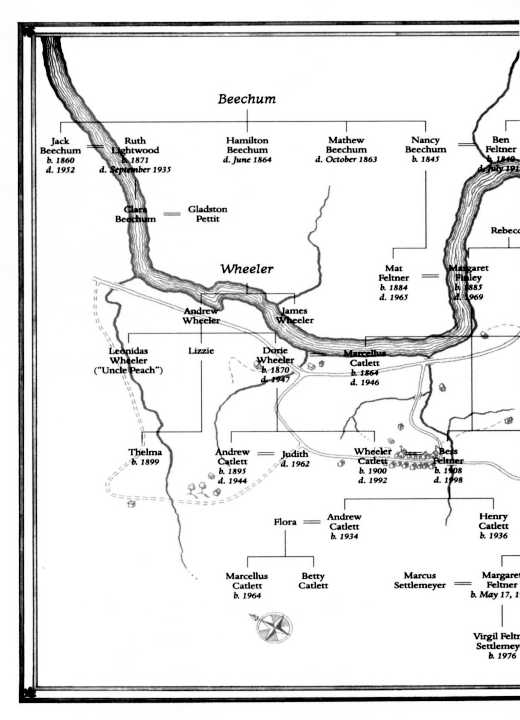

One by one, the sharers in this mortal damage have borne its burden

out of the present world: Uncle Andrew, Grandpa Catlett, Grandma,

Momma-pie, Aunt Judith, my father, and many more. At times perhaps I

could wish them merely oblivious, and the whole groaning and travailing world at rest in their oblivion. But how can I deny that in my belief

they are risen?

I imagine the dead waking, dazed, into a shadowless light in which

they know themselves altogether for the first time. It is a light that is merciless until they can accept its mercy; by it they are at once condemned

and redeemed. It is Hell until it is Heaven. Seeing themselves in that light,

if they are willing, they see how far they have failed the only justice of

loving one another; it punishes them by their own judgment. And yet, in

suffering that light's awful clarity, in seeing themselves within it, they see

its forgiveness and its beauty, and are consoled. In it they are loved completely, even as they have been, and so are changed into what they could

not have been but what, if they could have imagined it, they would have

wished to be.

That light can come into this world only as love, and love can enter

only by suffering. Not enough light has ever reached us here among the

shadows, and yet I think it has never been entirely absent.

Remembering, I suppose, the best days of my childhood, I used to

think I wanted most of all to be happy - by which I meant to be here and

to be undistracted. If I were here and undistracted, I thought, I would be

at home.

But now I have been here a fair amount of time, and slowly I have

learned that my true home is not just this place but is also that company

of immortals with whom I have lived here day by day. I live in their love,

and I know something of the cost. Sometimes in the darkness of my own

shadow I know that I could not see at all were it not for this old injury of

love and grief, this little flickering lamp that I have watched beside for all

these years.