A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 (18 page)

Read A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 Online

Authors: G. J. Meyer

Tags: #Military History

In 1830 the French seized control of Algeria in North Africa. At about that same time the British began building a power base in Arabia and the Persian Gulf. In 1853 Russia, tempted by what appeared to be easy pickings, invaded the Ottoman provinces south of the Danube. The Ottoman presence in Europe might have come to an end then if not for the Crimean War, in which Britain and France intervened to stop the Russians.

Britain, fearful that its position in the eastern Mediterranean and control of India might be lost if Russia broke through to the south, saved the Ottomans from destruction yet again in 1878. But by that time several European countries, Britain included, were feasting on the Turkish empire’s extremities. Austria-Hungary took possession of Bosnia and Herzegovina, literally preparing the ground for the Sarajevo assassination. France, with British support and in the face of such strong German opposition that for a time the issue threatened to spark a war, took Tunisia and Morocco in North Africa. Britain took Egypt and Cyprus, and finally even Italy reached across the Mediterranean to grab Tripoli (today’s Libya), along with islands in the Aegean and Mediterranean. Germany meanwhile, having arrived too late to share in this plunder, focused on building ties with the Turks. It began work on a Berlin-to-Baghdad railway, and Kaiser Wilhelm II paid a state visit to Constantinople and Jerusalem.

In 1908, the year when Austria-Hungary formally annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina, a group of would-be reformers called the Young Turks (their leader, an army officer named Enver Pasha, was only twenty-seven years old) seized control of the government in Constantinople and introduced a constitution. In 1912 the First Balkan War drove the Turks almost entirely out of the Balkans. This, and the failure of the Constantinople regime to deliver the reforms expected of it or to stop the disintegration of the empire, gravely damaged the prestige of the ruling faction, which was replaced by nationalist extremists once again led by Enver. Some of it was regained the following year, however, when the Second Balkan War led to Turkey’s recovery of the city of Adrianople on the European mainland. The sultan was at least as ridiculous a figure as the sorriest of his predecessors. (He had been deemed a safe choice for the throne after boasting that he had not read a newspaper in more than thirty years.) No one even pretended that he mattered. In January 1914, Enver Pasha left the army to become minister of war, and in July he took his empire into a secret defensive alliance with Germany.

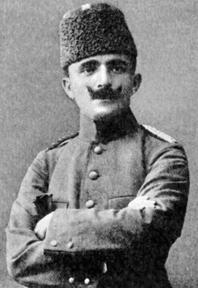

Enver Pasha War Minister and Young Turk

Eager to recoup the Ottoman Empire’s humiliating losses in the Balkans and elsewhere.

Astonishingly in light of all the humiliations it had experienced, the Ottoman Empire of July 1914 was still bigger geographically than France, Germany, and Austria-Hungary combined. It still ruled Arabia, which soon would emerge as the world’s greatest source of oil. If war did erupt, no one knew if the empire would enter it or, if so, on which side. It would be a coveted ally—or a rich, probably easy conquest.

Chapter 6

Saturday, August 1:

Leaping into the Dark

“If his majesty insisted on leading the army eastwards, he would have a confused mass of disorderly armed men.”

—H

ELMUTH VON

M

OLTKE

W

hy didn’t the Germans seize upon Tsar Nicholas’s eleventh-hour offer? Why didn’t they agree to do as the Russians were doing, mobilize their forces but at the same time pledge not to attack? Why didn’t they wait, pressuring Austria-Hungary to be sensible while Russia put pressure on Serbia and some sort of settlement was worked out? It was a splendid opportunity. Seizing it could have put Germany in a solid bargaining position.

It all came to nothing in part because of the unmanageable difficulties that mobilizing and then waiting would have created for Germany and Germany alone. An open-ended postponement of hostilities after the great powers had mobilized would have destroyed Germany’s chances of defeating France before having to fight Russia. It would have given Russia especially, but France as well, an advantage that could only grow as time passed. The high command of the German army would, understandably, have called any such postponement an act of madness. When the kaiser suggested something like it, Army Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke came close to calling the idea insane.

Ever since becoming chief of staff, Moltke had been developing a highly secret plan for fighting a two-front war. This came to be called the Schlieffen Plan, after the general who first conceived and proposed it, but it was Moltke who made it Germany’s only military option. By 1914 he had spent a decade immersed in it, tinkering with it, torturing himself about how to make it work. No matter how often or in how many ways he introduced new refinements, the plan continued to have one unchanging thesis at its center: speed was everything. Anything that slowed the Germans down, anything that might allow Russia to get into a war before France had been taken out, was regarded as likely to be fatal.

For this reason the tsar’s promise to “take no provocative action” while mobilizing was, from the German perspective, nonsense. General mobilization meant, by definition, that Russia was marshaling its forces for an attack on Germany. Every day of mobilization brought Russia closer to being ready to strike at Germany from the east as soon as Germany was ready to engage France in the west. Viewed from Berlin, Russian mobilization

was

a provocative action of the most serious kind. It was inherently threatening to an extent that the tsar and his advisers could not possibly have understood. And while the Russians hoped that mobilization, by demonstrating the gravity of the situation, would increase the willingness of the Central Powers to negotiate, actually it worked in the opposite direction. The Germans—fearful like all the great powers of appearing weak—were unwilling to give the appearance of having been forced to negotiate by the threat of Russian action.

But Germany’s mobilization problems went even deeper. Moltke, over the years, had transformed Schlieffen’s idea for a lightning-fast attack on France from an option into an inevitability in case of war. Any delay after mobilization had gone from being a danger into being an impossibility. Moltke and his staff gradually lost the ability to imagine situations in which delay might become advisable. Their planning became so rigid that it left Germany—today this can seem almost impossible to believe—with no way of mobilizing without invading Luxembourg and Belgium en route to invading France.

This was the self-created trap that the Germans found themselves in on August 1—a trap that gave the army’s high command no choice except to tell the kaiser that Tsar Nicholas was asking Germany to do the one thing that Germany absolutely could not do. Only Russia could now prevent war, the generals told Wilhelm, and Russia could do so only by agreeing to the terms of the double ultimatum.

At midday on the fifth Saturday since the murder of Franz Ferdinand, the deadline for the double ultimatum arrived without an answer from Russia or France. Kaiser Wilhelm, at the urging of Moltke and Falkenhayn and with the reluctant agreement of Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg, approved a declaration stating that because of St. Petersburg’s continued mobilization a state of war now existed between the two empires. This declaration was wired to Friedrich von Pourtalès, Berlin’s ambassador to Russia, with instructions to deliver it at six

P.M.

(It would not reach Pourtalès until five-forty-five, and he had to decode it before taking it to Sazonov.)

Later in the afternoon, when the German ambassador in Paris called on Viviani and asked for his government’s response to the ultimatum, he was told icily that “France will have to regard her own interests.” An hour later the French government declared a general mobilization—General Joffre, chief of the French general staff, was warning that every twenty-four hours of delay would cost ten or twelve miles of territory when the fighting began—and fifteen minutes after that Kaiser Wilhelm agreed to mobilization as well.

The German mobilization order was made public at five

P.M.

The kaiser had made its signing a solemn and, in an improvised way, a formal occasion, inviting Bethmann Hollweg and a number of Germany’s most senior military officials to serve as witnesses. After handshakes and words of firm resolution by men with tears in their eyes, they remained together to wait for word from Pourtalès. Their conversation turned into a discussion of what should be done next, which soon became a heated and somewhat confused argument. Long-bearded old Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, father of the High Seas Fleet that had poisoned relations with Britain, said that neither mobilization nor a war declaration was needed at this point—that all reasonable possibilities of a negotiated settlement should be allowed to play out. Almost everyone except the kaiser, who appeared to be uncertain, disagreed with Tirpitz, but not always in the same way or for the same reasons. Moltke and Falkenhayn remained firm on the need for mobilization without delay. Bethmann, who never would have assented to mobilization if Russia’s earlier mobilization had not been confirmed without possibility of doubt, said that a formal declaration of war was what was needed now.

The dispute was interrupted by the arrival of Gottlieb von Jagow, the head of the foreign office. Bursting into the room, he announced that a message had just arrived from Ambassador Lichnowsky in London. It was still being decoded but would be ready in minutes. It appeared to be important.

It was a good reason to delay the mobilization, said Tirpitz, at least until they knew what it was all about.

Rubbish, said Moltke and Falkenhayn, and they departed. They were off to oversee the mobilization.

The message from London proved to be not just important but astonishing. Lichnowsky reported that the British foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey, had just telephoned him with a momentous question. Grey wanted to know, the ambassador said, “if I thought I could assure him that in case France should remain neutral in a Russo-German war, we would not attack the French.” The question had come just in advance of a meeting of the British cabinet, and Lichnowsky had assured Grey “that I could take responsibility for such a guaranty, and he is to use this assurance at today’s cabinet session.”

The kaiser, when he had absorbed this, was almost beside himself with joy. So was Bethmann: it seemed almost too good to be true. It placed at Germany’s feet an historic diplomatic victory. The Germans were now free to bring Russia to heel virtually without risk and to restore Austria-Hungary’s position among the powers.

Moltke and Falkenhayn were intercepted and summoned back to the palace. The message from London was read to them. Then the kaiser gave new orders to Moltke:

“We shall simply march the whole army east!”

These words came as a blow to Moltke. He was the nephew and namesake of Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke, one of the greatest figures in German military history. The elder Moltke had led the Prussian army to victory over Austria in 1866, thereby establishing Prussia as the leader of the German states. He had then, in 1870, led the armies of Prussia and the German states allied with it in the defeat of France. His nephew had always enjoyed a special place in the army simply because of his name. It was almost certainly his name, in fact, that had propelled him to the top of the general staff. He was a stolid, insecure man, gloomy and filled with fear of the future, convinced that Germany’s enemies were growing stronger so rapidly that within not many more years the empire’s position would be hopeless. This fear had caused him to toy with the idea of preventive war (an idea that Bismarck had ridiculed as “committing suicide out of fear of death”), though he had never actually advocated or prepared for such a war. He was sixty-seven years old in 1914, with heavy jowls and too much flesh on what had once been his impressively martial frame, a weary man recovering from a bronchial infection, devoid of the slightest trace of charisma. No one had ever mistaken him for a military genius.