A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 (47 page)

Read A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 Online

Authors: G. J. Meyer

Tags: #Military History

The consequences were profound. Until the kaiser began his shipbuilding program, Britain and Germany had seemed designed by destiny not to conflict. Britain had the world’s greatest collection of colonies and greatest fleet of warships, but only a small and widely dispersed army and no ambitions on the European mainland. Germany’s overseas possessions were small by comparison, and it had no navy at all beyond a tiny coastal defense force. Both nations were focused on France, which for generations had been the most powerful country on the continent (it had taken Britain, Prussia, Russia, Austria, and Spain together to bring Napoleon down) and Britain’s great rival in North America and the Caribbean, Africa, the Middle East, and elsewhere.

Even after the Franco-Prussian War, which established the newly unified Germany as Europe’s leading power, Britain saw little reason to be concerned. She and Germany continued to regard each other as natural allies and old and good friends—a relationship personalized in the happy marriage of Queen Victoria’s daughter and the first kaiser’s son and heir. After 1890, when Russia and France became allies, whatever worries London might have had about Germany disrupting the European balance of power were temporarily put to rest.

But when Wilhelm II and Tirpitz embarked upon the building of a navy that they hoped to make as powerful as Britain’s, they threatened the foundations of British security. From the perspective of London, Germany was no longer a friend but a rival at best and a serious danger at worst. (The kaiser neither intended nor foresaw this change. At once jealous and admiring of a United Kingdom ruled in succession by his grandmother, his uncle, and his cousin, he entertained fantasies in which Britain would embrace Germany as its equal on a world stage that the two would govern to the benefit of everyone, including the “natives” of backward and faraway lands.)

The German navy was born in 1898, when legislation financed the construction of seven state-of-the-art battleships immediately and fourteen more over the next five years. This ignited an enormously costly arms race. Britain was able to pay for its shipbuilding with tax revenues, but the Germans, already spending heavily to keep their army competitive with those of France and Russia combined, had to borrow heavily. (Members of the Reichstag objected, but they had no authority over the naval budget.) Further naval construction bills were enacted in Berlin in 1900, 1906, 1908, and 1912, each one more costly than the last. In 1898 Germany’s annual naval spending had been barely one-fifth of the army budget. By 1911, with the army much bigger and more expensively equipped, the navy was costing more than half as much.

The result, for a nation with little in the way of a maritime tradition, was a surprisingly excellent navy, one whose ships and crews were by every measure at least equal in quality to those of the British. But London had done, and spent, still more. Admiral Sir John Arbuthnot Fisher—“Jacky” Fisher, the brilliant, dynamic, and strangely Asian-looking little first sea lord—radically reformed and upgraded the Royal Navy to trump the German challenge. Thanks largely to Fisher, in 1906 Britain launched a monster ship that revolutionized naval warfare: HMS Dreadnought, which at 21,845 tons was more than a fourth bigger than any battleship then in service, was sheathed in eleven inches of steel armor, carried ten twelve-inch guns capable of firing huge projectiles more than ten miles, and in spite of its size and weight could achieve a speed of twenty-one knots. When the Germans then built dreadnoughts of their own, the British responded by building still more, making them even bigger and arming them with fifteen-inch guns. It was a race the Germans could not win, but it went on.

Admiral Lord John Fisher

“Damn the Dardanelles—they will be our grave!”

Germany began the war with fifteen Dreadnought-class warships, each fitted with a suite of luxury quarters for the exclusive use of the kaiser, and five under construction. The British had twenty-nine and were building another thirteen. With France’s ten heaviest warships added to the equation, the Entente had an insuperable advantage. Neither side was willing to risk its best ships in all-out battle, the Germans because they were outgunned and the British because the loss of their fleet would mean ruin. And so the first months of war saw a distinctly limited naval conflict in which no dreadnoughts were involved.

That war was a costly one despite its limits. It showed the Germans that their High Seas Fleet was not big enough to compete, and the British that they could keep that fleet bottled up in port but not destroy it. On August 28 a British foray at Helgoland Bight in the North Sea turned into the war’s first naval battle; three German cruisers and one destroyer were sunk. On September 3, north of Holland, a single German submarine sank three antiquated British cruisers, fourteen hundred of whose crewmen were lost. On November 1 five German cruisers commanded by Admiral Maximilian von Spee met and defeated the Royal Navy’s South American squadron off the coast of Chile, sinking two cruisers and badly damaging a third. Fisher, retired in 1910, had been called back to active duty by Churchill after war hysteria forced Prince Louis Battenberg to retire as first sea lord because of his German antecedents. (The family soon changed its name to Mountbatten.) Dispatching a task force of two battle cruisers (smaller than dreadnoughts and battleships), three armored cruisers (smaller still), and two light cruisers to South America, Fisher ordered Admiral Sir Frederick Sturdee not to return until Spee and his ships had been destroyed. On December 8 Spee raided Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands and was surprised to find Sturdee already there, taking on coal. Spee fled and Sturdee pursued, catching up with the slower German ships and sinking all but one. Spee went to the bottom with his flagship and his two sons.

Later that month German battle cruisers shelled three towns on England’s east coast, killing a number of civilians. In January British and German ships clashed inconclusively—there were no sinkings—at Dogger Bank in the North Sea. Surface combat then came to an end, the British satisfied to keep the Germans in port and Kaiser Wilhelm, in the face of protests from Tirpitz, unwilling to send his fleet out to engage them.

The Royal Navy had by this time clamped down a naval blockade that cut off most of Germany’s imports. In violation of international agreements, the Asquith government declared that the entire North Sea was a war zone in which not only German but neutral ships would be boarded, searched, and prevented from delivering cargo of any kind (food and medicine included) to places from which it might be forwarded to the Central Powers. Even neutral ports were blockaded, with most of Germany’s merchant fleet interned therein. The British and French, meanwhile, were using their control of the world’s oceans to move troops and supplies wherever they chose—to Europe from India, Africa, Australia, Canada, and the Middle East, and from Europe to the Mediterranean.

Berlin responded with a new and still-primitive weapon that was the only kind of ship it could send into open waters with any hope of survival. On February 4, though they had fewer than twenty seaworthy submarines (Britain and France each had more, Fisher having insisted on adding them to the Royal Navy during his first tenure as sea lord), Germany declared that the waters around Britain and Ireland were to be regarded as a war zone in which all ships, merchantmen included, would be fair game.

Like poison gas and the machine gun, like the airplane and the tank, the submarine was something new in warfare. Both sides needed time to adapt to it. Only the Germans went after commercial shipping, because there was no German commercial shipping for the Entente’s submarines to sink. At first they observed traditional “prize rules,” according to which naval vessels were supposed to identify themselves (which in the case of the submarines meant surfacing) before attacking nonmilitary ships and allow passengers and crews to depart by lifeboat before torpedoes were fired. Such practices proved dangerous for the tiny, fragile, slow-moving and slow-submerging U-boats. They became suicidal when the British began not only to mount guns on merchantmen but to disguise warships as cargo vessels in order to lure submarines to the surface. The prize rules were soon abandoned.

The U-boats (

Unterseebooten

) sank hundreds of thousand of tons of British shipping, suffering heavy losses themselves in the process. They were, however, of little real value. At its peak their campaign was stopping less than four percent of British traffic but was arousing a ferociously negative response not only in Britain but in the United States. The German foreign office, fearful of American intervention, tried to persuade the kaiser that the U-boats’ successes were not nearly worth the risk. Most leaders of the German army and navy demanded that the campaign continue.

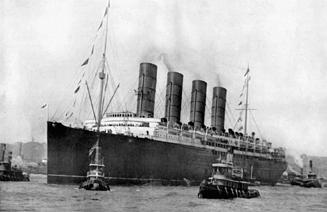

On May 1 the German consulate in New York ran newspaper advertisements warning readers of the dangers of sailing on the Lusitania, a British Cunard steamship famous as the biggest, fastest liner in Atlantic service. Less known was the Lusitania’s status as an “auxiliary cruiser” of the Royal Navy. Its construction had been subsidized by the government, which equipped it with concealed guns, and it almost certainly had American-manufactured guns and ammunition as part of its cargo for the May crossing.

The “auxiliary cruiser” Lusitania embarking from New York Harbor on her last Atlantic crossing

On May 7, passing close to Ireland as it neared the end of its voyage, the

Lusitania

turned directly into the path of the patrolling submarine U-20 and was torpedoed. It sank in twenty minutes after a massive second explosion that soon would be attributed to the German commander’s gratuitous firing of a second torpedo into the mortally wounded ship but has since been traced to an ignition of coal dust in empty fuel bunkers. Some twelve hundred passengers and crew drowned, 124 Americans among them, and the United States erupted in indignation. German diplomats warned with new urgency that the U-boat attacks must stop, and on June 5 an order went out from Berlin calling a halt to the torpedoing of passenger liners on sight.

Chapter 15

Ypres Again

“Out of approximately 19,500 square miles of France and Belgium in German hands, we have recovered about eight.”

—W

INSTON

C

HURCHILL

A

s March turned to April the leaders of the Entente had reason to be satisfied with how the war was going for them in the East. The Russian offensive against Austria-Hungary in Galicia and the Carpathians—the same offensive that had taken Przemysl—continued to make headway despite lingering winter weather and chronic shortages of weapons and ammunition. (Ludendorff wrote admiringly of how the Russian soldiers, attacking uphill and armed only with bayonets, displayed a “supreme contempt for death.”) The Russian Eighth Army, commanded by the able and aggressive General Alexei Brusilov, was capturing miles of the Carpathian crest and the passes leading to the Danube River valley. Russian control of Galicia was so secure that the tsar himself visited the conquered city of Lemberg (Lvov to the Russians, now Lviv in Ukraine), where he had the satisfaction of sleeping in the suite that until then only Emperor Franz Joseph had been allowed to use. A massive Russian move beyond the Carpathians seemed inevitable by spring or early summer. The Austrians, frightened, knew that they had little hope of fending it off. The Russians were so confident of their prospects that they no longer saw any need to offer a rich share of their anticipated postwar spoils in order to draw Italy into the war. And they were being successful enough against the Turks in the Caucasus to make a Dardanelles campaign seem no longer imperative or even particularly desirable except in connection with a Russian advance on Constantinople.