A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 (96 page)

Read A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 Online

Authors: G. J. Meyer

Tags: #Military History

Even in the short term, the treaty was a greater misfortune for Germany than for Russia. The Bolsheviks gave away little—what they surrendered was beyond their power to hold. The Germans got a liability of enormous dimensions. At a time when they needed every available man and gun and locomotive in the west, they took on a new, ramshackle, unmanageable, and doomed eastern empire, the occupation of which would require one and a half million troops. They had to send soldiers to subdue Finland, Romania, Odessa, Georgia, Azerbaijan—an almost endless list of distant places with little relevance to the outcome of the war. Ukraine alone soaked up four hundred thousand German and a quarter of a million Austro-Hungarian troops. And for what? The payoff never came. Ukraine was supposed to become a bread basket for the starving populations of the Central Powers. But the troops sent there consumed thirty rail cars of food daily. The grain that eventually reached the German and Austrian home fronts was never more than ten percent of what had been hoped for. The situation would continue to deteriorate, compounding the problems of the Germans, as civil war erupted in Russia and its former possessions.

Even this outcome was overshadowed by the impact that Brest-Litovsk had on Germany’s principal enemies. The draconian treatment of Russia was taken as a stern lesson in what had to be expected if imperial Germany was not broken. Those leaders most determined to fight on—Lloyd George for one, Clemenceau for another—could claim to have been vindicated. On both sides of the Western Front, potential peacemakers were left without influence.

Ludendorff could scarcely have cared less. He basked in the satisfaction of having achieved a triumph as complete and world-changing as any in history. In the west he was assembling an astoundingly powerful force—191 divisions, three and a half million men—trained in new tactics and eager to put them to work.

He was within days of bringing down on his enemies the greatest series of hammer blows in the annals of war. If he could succeed this one last time, Germany would be master of east and west.

Background

LAWRENCE OF ARABIA

BY THIS TIME A WHOLE OTHER WAR, ONE BETWEEN THE

British and the Turks (but with Arabs doing much of the fighting and dying), was growing up from small beginnings on the fringes of the Sinai Desert east of Suez and west of Palestine. Even at its height it would be a tiny war compared to what was happening in Europe, and viewed from a sufficient distance it could seem a wonderfully exotic affair.

It was also more fertile ground than the battlefields of Europe for the emergence of heroes. Trenches and massed artillery and machine guns had a way of putting would-be heroes underground before they properly got started. But in the desert, men wearing burnooses rode camels into battle. Even an Englishman could do so. Out of that possibility grew the greatest romantic story of the Great War, the legend of Lawrence of Arabia, the man the Bedouins called El Aurens.

The story began in the Egyptian capital of Cairo in September 1916, with the preparations of a British diplomat named Ronald Storrs to travel into the Hejaz region east of the Red Sea. Storrs wanted to make contact with the followers of Sherif Hussein, Arab emir of the sacred city of Mecca. The British had earlier duped and bribed Hussein, making promises they had no intention of keeping, to get him to raise a rebellion against the Ottoman Empire. He had done so, and the Turks had responded. In February and again in August, Turkish troops led by German officers had unsuccessfully attacked the Suez Canal, which ran north and south along the western edge of the Sinai and was the jugular through which Britain maintained contact with India and the Far East. Though thrown back, the Turks were threatening to take Mecca from the Arab rebels and crush Hussein’s small force of warrior-tribesmen.

A young and very junior lieutenant, Thomas Edward Lawrence, requested permission to accompany Storrs. Still in his twenties, a deskbound intelligence officer with no military experience or training, Lawrence was on the staff of a recently created entity called the Arab Bureau, which was to develop policies to guide British relations with the Arabs. Lawrence said he wanted to gather information about how the Arab troops were organized, and to identify competent, dependable Arab leaders. His superiors granted his request; evidently he was not popular among the Cairo officer corps, so that “no one was anxious to detain him.”

It was a perfect meeting of man and situation. One of five sons of a baronet named Chapman and the governess with whom he had run away from his first family—creating such a scandal that they had adopted a new family name—he already had extraordinary knowledge of the Arabs and their world. As a student at Oxford he had become fascinated with medieval military fortifications, and while still an undergraduate he traveled through Ottoman Syria and Palestine studying castles constructed by the crusaders. The resulting thesis, later published in book form, led to a degree with highest honors and a traveling fellowship. From 1911 to early 1914 Lawrence worked on archaeological digs and broadened his knowledge of Arabia, its people, and their language and culture.

In England when the Great War began, he joined the war office in London and was put to work making maps. Before the end of the year he was given a commission and sent to Cairo. Though he looked utterly unlike the Peter O’Toole who would one day play him on the screen (Lawrence was short and lantern-jawed), he had exceptional intellectual gifts and made himself valuable during a year spent questioning prisoners, analyzing information procured from secret agents, and continuing to make maps. His appreciation of the magnitude of the war on the far-off Western Front was no doubt strengthened by the death of two of his brothers there in 1915.

Though his background and peculiarities (which included a powerful masochistic bent) meant that Lawrence had a limited future at best in the regular army, from the start of the Storrs mission his liabilities became assets. Instead of returning to Cairo with the rest of the mission, Lawrence went deeper into the Arabian desert, traveling by camel and adopting Arab garb (the only sensible way to dress in that uniquely inhospitable environment). South of the city of Medina he met one of Hussein’s sons, Prince Feisal. The two quickly formed a bond. When Lawrence returned to Cairo, he told his superiors that the Arab revolt had the potential to seriously weaken the Turks everywhere from Syria southward, that Feisal was the man to lead it, and that he should be given money and equipment. Lawrence was sent back into the desert to become Britain’s liaison and to deliver promises of support.

This eccentric academic intellectual turned out to be a guerrilla fighter of almost incredible courage, a shrewd military strategist, an absolutely brilliant tactician, and an inspiring leader of Arabs. Having won the confidence of Feisal, he was able to open a new, miniature, but important, front. It became a war of his own creation, it kept the Turks constantly off balance, and ultimately it would protect the flank of a conventional British force moving out of Cairo to the conquest of a Sinai, Palestine, and Syria. Coming at the same time as the collapse of Bulgaria, which opened Constantinople to attack out of the Balkans, the advance into Syria would help make it impossible for Turkey to continue the war. By then young Lawrence was a lieutenant colonel and holder of one of Britain’s highest military decorations, the Distinguished Service Order or DSO.

Lawrence’s approach was to probe into enemy territory with the smallest, most mobile force possible, hitting hard and escaping quickly. He led the raids that he planned, taking the Turks by surprise by approaching across murderously hot and waterless wastes, blowing up bridges and railways, then disappearing back into the desert. He was engaged in countless gun battles, was wounded several times, and was once captured while on a spying mission by Turks who didn’t know who he was but beat him severely before letting him go. Probably he was sexually assaulted during this episode, though in later years he was evasive on the few occasions he made reference to it. The war in the desert was a savage affair in which terrible atrocities were committed by both sides. At the same time that Lawrence’s activities made him an international hero (an American journalist named Lowell Thomas brought his exploits to the world’s attention), they left him physically and emotionally exhausted and psychologically damaged.

The traumatic effects of the war were worsened, for Lawrence, by the knowledge that Britain was deceiving Hussein, Feisal, and the Arabs generally. Britain and France had signed but kept secret the Sykes-Picot Agreement, according to which, after the war, the southern parts of the Ottoman Empire were to be divided between the two. Britain was to get southern Mesopotamia (Iraq to us) and ports on the Mediterranean. Lebanon and Syria were promised to France. The Arabian Peninsula was to be divided into spheres of influence that, if nominally autonomous, would be dominated by the Europeans.

Sykes-Picot could not be reconciled with what the Arabs had been promised: autonomy across their homeland, from the southern tip of the peninsula up through Lebanon and Syria. Lawrence revealed much of the true situation to Feisal, urging him to strengthen the Arabs’ bargaining position by capturing as much territory as possible before the war ended. Though his credibility with the Arabs was enhanced when the Bolsheviks published the details of the Sykes-Picot deal in 1917, his position remained difficult all the same. When it became certain, after Damascus fell to the Allies, that the pledges made to the Arabs were not going to be redeemed, Lawrence departed for London without waiting for the war to end.

His postwar life would be as improbable as his wartime career, though in a radically different way. He refused a knighthood and promotion to brigadier general, resigning his commission instead. He went to the Versailles Peace Conference, where he appeared in Arab headdress and robes and lobbied in vain on behalf of the Arabs. Thereafter, offered lofty academic positions and high office by Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill, he joined the Royal Air Force as a private under the name Ross. When this was discovered and became a sensation in the press, he was discharged. With the help of influential friends, he became a private in the Royal Tank Corps, this time using the name Shaw. In the years that followed he kept this identity but simultaneously produced books that are today minor classics, maintaining friendships with some of the important literary and political figures of the day. He retired from the RAF in 1935, moved to a cottage in the countryside, and died, forever mysterious, in a motorcycle accident.

Chapter 33

Michael

“There must be no rigid adherence to plans made beforehand.”

—G

ERMAN INFANTRY MANUAL

L

udendorff’s hammer came down on the British through an impenetrable fog early on the morning of Thursday, March 21, shattering everything it struck. For a long breathless moment, the fate of Europe hung in the balance.

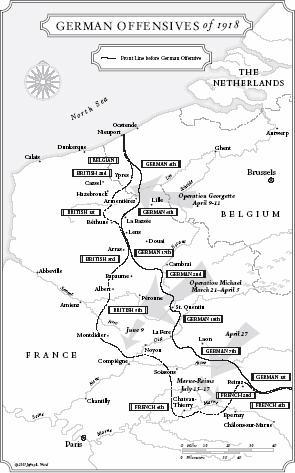

The force of the blow was magnified by surprise. In spite of the immensity of their preparations—building up huge ammunition dumps, concentrating sixty-nine divisions and more than sixty-four hundred guns between Arras to the north and St. Quentin to the south—the Germans had managed to keep their intentions secret. By early March Haig and Pétain knew that an offensive was coming: troop movements on such a scale could not be concealed and could not be without purpose. But the Germans had been in motion all along the front that winter as Ludendorff, unable to decide where to attack, ordered his generals to be ready everywhere. It was impossible to know which movements actually mattered. The final placement of the guns did not begin until March 11. The assault divisions did not start for the front until five days after that, and even then they marched only by night, staying under camouflage by day. Between February 15 and March 20 ten thousand trains hauled supplies forward, but they too moved by night. Early in March Ludendorff moved his headquarters to Spa, in southeastern Belgium. On March 19 he moved again, to Avesnes in France.

Ludendorff had had 150 divisions in the west in November. By mid-March the total was 190—three million men, with more on the way. And to the extent that after years of slaughter there was still cream at the top of the German army, Ludendorff had drawn it together for this operation. He had refined it with a winter of training. The results were at the front in the predawn fog of March 21: forty-four divisions of storm troops, young men at the peak of preparation, equipped with the best mobile weapons that German industry could produce. Many of these soldiers were veterans of the eastern war, experienced in movement and accustomed to winning. They brimmed with confidence. Told that they were opening the campaign that would end the war, they were eager to believe.