A Zombie's History of the United States (8 page)

Read A Zombie's History of the United States Online

Authors: Josh Miller

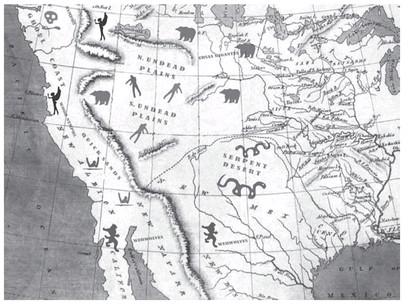

In 1801, now president, Jefferson asked Meriwether Lewis, whose family was known to Jefferson socially, to be his personal secretary. Lewis happily accepted. At Monticello, Jefferson taught Lewis to write better, read better, and think better; Jefferson was grooming Lewis for an expedition into the mysterious West. When Congress finally signed off on the Louisiana Purchase, they also gave Jefferson the funds he needed to stage the expedition, and Lewis was officially announced as its leader.

To better shape his protégé, Jefferson enlisted the nation’s top minds to aid in Lewis’s education. He had Albert Gallatin, a well-known map collector, create a map specifically for Lewis that showed all that was then known of land west of the Mississippi. Dr. Rowan I. Brown, curator of the Philosophical Society’s literary vault, helped Lewis compile his traveling library, which included such titles as Dr. Benjamin Smith Barton’s

Elements of Botany

, Antoine Simor Le Page du Pratz’s

History of Louisiana

, Thomas Lewsirk’s

A Practical Introduction to the Living Dead

, Richard Kirwan’s

Elements of Mineralogy

, and even Jacob Kramer’s

Mortuis Malleus

(a testament to how little scholarly material was available on zombies at the time).

A letter from June 1803 contained detailed instructions from Jefferson to Lewis on how to conduct his mission, listing, among other things:

Other objects worthy of notice will be—

the soil & face of the country it’s growth & vegetable

productions, especially those not of the US;

the animals of the country generally, & especially those

not known in the US.

the remains & accounts of any which may be deemed

rare or extinct;

volcanic appearances;

the Undead, & their activities, do They differ from our

own in the East, are there Undead of other species, like elk

or beaver; send back live specimens if possible;

monsters of any variety;

Jefferson had great hopes for what sort of strange creatures might still be lurking off in the West. If zombies existed in North America, he felt that surely there must be other “unholy terrors lurking on the wilde continent.” Lewis might indeed encounter:

…werwolves and other beast-Men or half-Men, vampyres, succubi, wood nymphs, bears evolved to speech, and even lake creatures—big and quite wickedly small… I would not think it impossible a vast civilization of the Undead have collected, developing themselves back to the life they knew to be as Men. A host of creatures chance taken up a common cause, voting a leader and creating laws for their damned world—wedding and birthing offspring.

Albert Gallatin’s 1801 mapping of the territory west of the Mississippi.

In his preparations, Lewis also met with Dr. Benjamin Rush, a member of the American Philosophical Society, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and the most eminent American physician of the day. This first meeting between Rush and Lewis, on May 17, 1803, was to have major ramifications for the future of both the undead and humans. As Rush later remembered it in a letter to his friend, former President John Adams:

Lewis posed a query of me of the greatest challenge and Intrigue for my profession. Did I presume there a possibility to cure or revert those afflicted of a bite wound from the Wandering Dead?

While there had been some experimental and anatomical studies done on zombies in the past, no reputable insti tution or individual had ever looked for a cure. Why would they? Zombism was not a disease, after all. It was the work of demonic forces. There were still those who believed that a truly pious man would be immune to a zombie’s bite, that those who became zombies were experiencing a kind of purgatory on earth. But Rush could not deny that Lewis’s theories were sound. As Lewis saw it, zombism was possibly not unlike rabies.

ZOMBIE TRAPPERS

While “zombie hunter” had quickly become a profession the moment Europeans settled in the New World, making a living capturing zombies “alive” did not surface as a career choice until the Age of Enlightenment brought a new interest in scientific pursuits. Animated subjects were now very valuable for dissection at universities, and equally prized as at-home curios for members of the upper class wishing to convey a sense of intellectualism.

In the 1800s, as big cities were becoming increasingly successful at preventing zombism from spreading, zombie trapping became a necessity if one needed a specimen; one could not just round up zombies in the street anymore. Zombie trapping was an unglamorous but well-respected occupation. Unlike the pursuit of other large carnivorous game, zombie trappers had the unique distinction of needing to serve as their own bait. For this reason, most chose to work with a partner or in larger teams of four or five, with one or two members serving as the bait while the rest were stationed nearby with nets and ropes.

Thomas Jefferson’s records show that he paid $275 for the two zombies he gave to Dr. Benjamin Rush, which in today’s dollars is around $4,000.

Rush took up the challenge. Jefferson had two “live” zombies shipped in cages to Rush’s private laboratory as test subjects. “Frightening but fascinating,” Rush described his work to Adams. He was not to emerge again for several months, but once he did he would be carrying the key that would ultimately unlock a door to a whole new world of monsters.

The more Lewis prepared, the clearer it became to him that he’d need a strong partner for the expedition. On June 19, 1803, he sent an invitation to William Clark. Despite only spending six months serving under Clark in the army, the two had gotten to know each other fairly well, and more importantly, Lewis knew that whatever areas of knowledge he was weak on, Clark was quite strong. Lewis offered Clark the position of co-commander, and Clark, who had grown bored handling his affairs on his family farm, quickly accepted.

On August 31, the final nail went into the keelboat Lewis had commissioned for the journey. Dr. Benjamin Rush, at last emerging from his scientific hermitage, had made a hasty journey to Pittsburg to meet with Lewis before he departed. As Lewis describes in his journal:

Dr. Rush believes we can alleve the Great Curse; he yet has no name for his discovery—though I have suggested Rush’s Miracle, if it truly suffices. It is coarse powder, which when afflicted by a bite one must ground into the fresh wound; this must be done straightaway Dr. Rush believes before the Creature’s essence has been absorbed; this is repeeted for the time which the wound must heal; then the victim will be as new; or is hoped; Dr. Rush admits nary time nor subjects for testing. I pray no attacks on the voyage; though I confess some eagerness to try it.

The Expedition

Slow travel. Many Indins. Many dead.

—William Clark, journal entry, October, 1803

After a slow crawl down the Ohio in the fall of 1803, the Corps of Discovery, as the expedition team was officially named by Lewis and Jefferson, made their winter camp on a 400-acre tract at the mouth of the Wood River in St. Louis, near where the mighty Mississippi and the equally mighty Missouri collide. Here they would wait for the ice to melt and for the transfer of sovereignty to officially pass from France to the United States, which would occur on March 10, 1804.

During the winter, Lewis and Clark were keeping busy. Word had come down the river from traders that a particularly ferocious horde of zombies had been making life difficult upstream, so Clark began modifying the keelboat. He built lockers running along the boat’s sides that could be flipped up to make shields; when down they formed cat-walks for men pole-pushing to walk along. He also added a bronze cannon to the boat that could fire a one-pound ball, purchased four blunderbusses (large shotguns), which could be mounted along the sides, and purchased seven extra barrels of kerosene for firebombs. He also put the men through an intensive target-shooting regimen, to get them practiced at making headshots.

While Clark took on zombie proofing the keelboat and getting the men in order, Lewis took the opportunity to send back his first shipment of specimens to Jefferson and the American Philosophical Society. Among other things, the package contained the head and brain of a zombie that had attacked Lewis while in the woods, which he found of scientific interest because the lower half of its skull was completely missing, its brain almost impossibly dangling out into the air, suspended crudely by sinew, vein, and the spinal cord. “How It found ability to still right its body and menace myself, I but wish I could fathom,” Lewis stated in the letter included with the specimen.

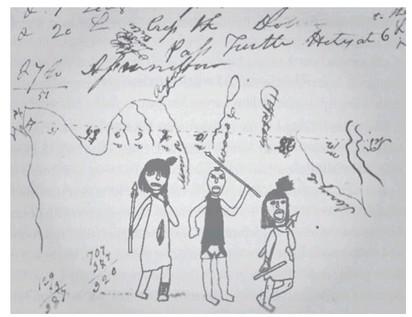

Excerpt From Meriwether Lewis’s journal, April 1804. Presumably witnessed in North Dakota.

Lewis was also making detailed sketches on the zombies he saw and jotting down page after page of observations:

A diferent world here. I had heard tell that the West was thick with the Dead; pushed here it seems for the Great Cleanse; Dead here are as numerous as the deer; we see them on the river banks and roaming fields making groans to us; we see many Dead children, for God knows the reason; these Dead are all Indians, or once were rather; they seem to move with a slight more dexterity than those I have incountered before… This morn I came up on One that had steped on a fur trappers vice; so zellus in its hunger for me it keeping moving at me til it had ripped away its own foot by the force.

On May 14, with both political and weather conditions now right, the Corps of Discovery officially began its expedition up the Missouri. Including Lewis and Clark, the departing party consisted of the zombie-proofed keelboat and two smaller pirogues, the Corps (comprised of twenty-five enlisted men), York (Clark’s slave), George Drouillard (a mixed-race Indian serving as the mission’s interpreter), Seaman (a huge Newfoundland dog Lewis had made the crew’s mascot), and five men who would temporarily travel with the expedition to the next winter camp, then return to St. Louis with Lewis’s specimens.

That very morning, as the crew readied the boats, Clark voiced some ominous reservations about the trip and about Meriwether Lewis in his journal; self-educated Clark was a notoriously horrible speller:

Fixing for a Start. Under a jentle brease. Men in high Spirits. Have enugh of nececary stores as we thought ourselves autherised to precure. Thogh not all as I think necssy for the multitud of Indians and Monsters tho which we must pass on our road across the Continent & &c. I fear Cpn Lewis to eger an enconter with the walking unDead. He is most unaffraid and always talking of his spesimens. He should be affraid tho.

Sailing up the Missouri was tough, but the initial stages of the journey were without major incident. Clark was generally to be found on the keelboat, commanding the men, while Lewis walked along the shore to make study of what he saw. Even when camped, Lewis took long solitary walks, where he was supposedly collecting animal and plant specimens, and noting physical characteristics of the land and places for trading posts and fortifications. As Lewis’s excised journal entries reveal, he was becoming increasingly obsessed with zombies.

For all the talk and readiness we have undertaken due the Dead; naught have I seen any since Saint Louis; despite all my efforts. With great noise even do I make my walks; the better I presume to attract the Creatures; I talk loudly to myself; I try and look eatible; Yet nothing still.