Abandoned in Hell : The Fight for Vietnam's Firebase Kate (9780698144262) (2 page)

Read Abandoned in Hell : The Fight for Vietnam's Firebase Kate (9780698144262) Online

Authors: Joseph L. (FRW) Marvin; Galloway William; Wolf Albracht

of Military Terms

12.7:

PAVN (see below) 12.7 mm (.51-caliber) machine gun often used in an anti-aircraft role.

105:

A howitzer firing 85-pound explosive shells that are 105 mm (4 inches) in diameter.

155:

A howitzer weighing six tons and firing 100-pound explosive shells that are 155 mm (6 inches) in diameter.

AK-47:

Chinese, Russian, Viet Cong, and PAVN infantry rifle. Fires semi or full auto.

Arc Light:

A B-52 strike.

ARVN:

Army of the Republic of [South] Vietnam.

B-40:

A rocket-propelled grenade, also called an RPG.

Chief of Smoke:

The senior noncom in charge of an artillery battery's guns.

CIDG:

The Civilian Irregular Defense Group, a sort of militia, used for

defense of Montagnard and other rural villages. They were led by US Special Forces troops.

Cobra:

Fast, extremely agile, and heavily armed helicopter used as a gunship.

commissioned officer:

Appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate to serve in pay grades from second lieutenant through general.

CONEX:

A large steel shipping container with doors.

deuce-and-a-half:

A 2.5-ton (cargo capacity) truck.

Also:

Six-by (6x6 for six wheels with driving power).

dink:

Pejorative term for a Vietnamese individual of any description, but especially the enemy.

FAC:

Forward air controllerâArmy or Air Force officer in a small plane who directs the activities of attack aircraft in support of ground troops.

fast mover:

A USAF or USN jet aircraft that carries bombs, rockets, and cannon.

Firebase Kate:

Small hilltop with three US howitzers and crews, a fire direction center, two Special Forces dudes, and 156 CIDG strikers (after reinforcement).

gook:

Derogatory slang for an Asian, especially one with a weapon.

Green Weenie:

The Army Commendation Medal.

hooch:

A dwelling. It might be a hole in the ground or a cinder-block building. On Kate it was usually a hole in the ground, covered with sandbags.

Huey:

One of several different models of the UH-1, a jet-turbine-powered helicopter used in a variety of configurations as cargo/troop carrier, gunship, command and control center, and platform for collecting intelligence or spraying various chemicals.

Lima Charlie:

Military phonetic alphabet for “loud and clear.” Also “Five by five.”

LOACH:

Small, agile, unarmed helicopter used for reconnaissance, observation, and carrying small loads.

M16:

Basic US Army rifle. Uses a 20-round magazine and fires semi or full automatic.

M79:

A shotgunlike weapon that fires a 40 mm grenade at ranges up to 450 meters.

MACV:

Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. The umbrella organization for all US military in Vietnam.

Mike Force:

An elite force of volunteer strikers (see below) held as a general reserve and used in the most serious situations. Led by US Special Forces and Australian Special Air Service noncoms and officers.

military time:

Midnight is 2400. Noon is 1200. A minute after midnight is 0001.

MOS:

Military occupational specialty.

noncom:

A noncommissioned officer, e.g., a corporal or a sergeant of any pay grade, appointed by authority of the Secretary of the Army.

Also:

NCO.

NVA:

North Vietnamese Army (see PAVN below).

OCS:

Officer Candidate School. A demanding, six-month path to becoming a commissioned officer.

Old Man:

A commanding officer, whatever the chronological age or gender.

PAVN:

People's Army of [North] Vietnam. The regular army of the Hanoi regime.

PIO:

Public information officer. Army public relations and media liaison.

Prick 25:

AN/PRC 25 backpack radio, 20 pounds with battery; operates on FM frequencies.

punji pit:

A hole filled with sharpened bamboo slivers, often coated with excrement.

push:

A radio frequency.

regenerate:

To refuel and rearm an aircraft to prepare it to resume a previous mission or begin a new one.

RPG:

Rocket-propelled grenadeâfires B-40 rocket with explosive warhead up to 200 meters effective range.

RTO:

Radio-telephone operator.

TAOR:

Tactical area of responsibilityâthe geographic area over which any particular unit was expected to operate in and exercise military control over.

TOC:

Tactical operations centerâa bunker or tent where combat operations were planned and monitored.

Shadow:

An AC-119G gunship similarly equipped as a Spooky (see below).

slick:

Huey (see above)

configured to carry troops and cargo.

SPAD:

USAF A-1, a single-engine attack plane that carried 4 tons of ordnance and enough fuel to loiter for hours over the battlefield.

Special Forces:

Elite US unit trained in unconventional warfare.

Spectre:

AC-130H, the USAF's newest and most fearsome gunship, armed with 20, 40, and 105 mm cannon and a host of defensive devices.

Spooky:

AC-47 (DC-3) aircraft converted to gunship with three electrically driven Gatling guns firing 6,000 bullets each per minute.

striker:

A Yard (see below) who serves in the CIDG.

VNAF:

The South Vietnamese Air Force.

warrant officer:

A rank above sergeant major and below second lieutenant. Rates a salute by lower ranks, receives pay similar to junior officers, but is limited to technical specialties. Most Army warrant officers are helicopter pilots, and most Army pilots are warrant officers.

Yard:

Slang for Montagnard, a member of one of thirty indigenous tribes that inhabit the Central Highlands. Small, dark-skinned, and no friend of the lowland Vietnamese, who regarded them as dangerous savages.

Not for fame or reward, not for place or for rank, not lured by ambition, or goaded by necessity, but in simple obedience to duty as they understood it, these men suffered all, sacrificed

all, dared all.

âRandolph Harrison McKim, inscription on the

Confederate War Memorial, Arlington National

Cemetery

T

his is the tale of an almost forgotten fight for a small, worthless hilltop in Vietnam's Central Highlands. It is about some of the finest soldiers who ever served their country. It is a chronicle of shared hardship and danger, of the very young men with whom I served and their constant, casual courage. It is an attempt to describe functioning as a soldier while gripped by deathly fear, the soul-shattering effects of betrayal, and the lifetime bonds that form between fighting men. It is also about the life-changing loss of innocence that follows the death of a close comrade. In a lesser way, it is about a tiny part of a large, strategically vital campaign.

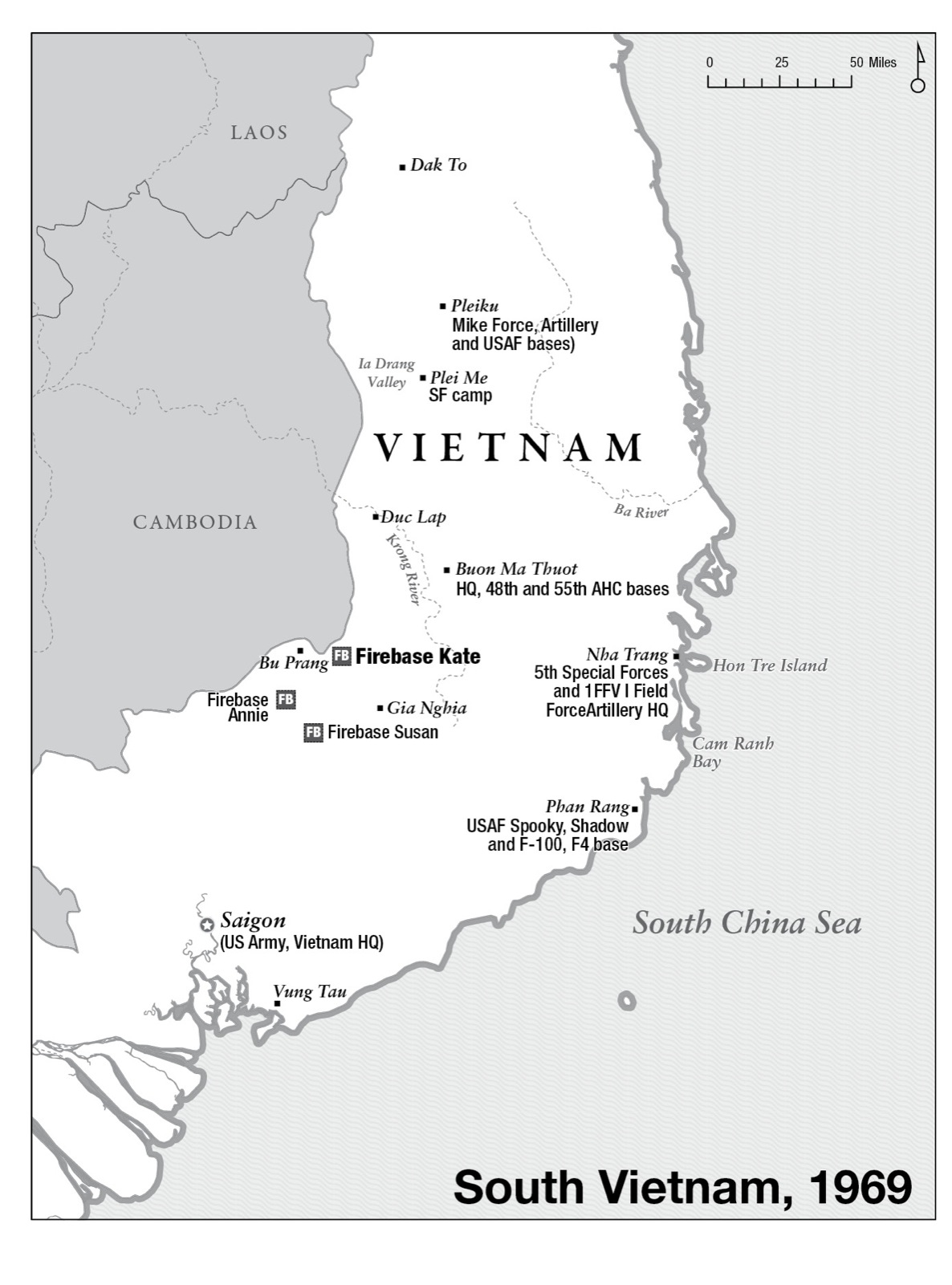

The five-day siege of Firebase Kate took place in 1969, at a turning point in what now seems like an ancient and misbegotten conflict. Four years earlier, American ground forces went to war against a well-armed and highly motivated North Vietnamese invasion force. America sent its best troops into battle, sent them to grapple with the enemy, to punish and to kill, certainly, but also to take our foe's measure and to learn if and how a road to victory was possible.

The year 1969 marked the abandonment of that road. Kate was an

ephemeral, cautionary signpost in history's rearview mirror on what would become a detour to a costly and ignominious failure.

As late as the previous year, the route to American victory had appeared to be well paved and wide-open. Defeated in the field at every turn, the Viet Cong were seemingly reduced to small, mostly homegrown guerrilla bands. They were a nuisance, but no longer much of a threat. The 1965 invasion by the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN), as the North Vietnamese Army called itself, had been turned around by a half million American and Allied troops. Pursued by our highly mobile infantry, attacked high and low by our deadly warplanes, pounded by our armed helicopters and long-range artillery, the PAVN fought hard and fought well but repeatedly was forced to retreat to its sanctuaries in supposedly neutral Cambodia and Laos. Hanoi's official records show that at least twenty-four PAVN or Viet Cong were killed for every American whose name would be engraved on our wall of tears on the Washington Mall.

Meanwhile, day after day, US bombers flattened Hanoi and its environs, to say nothing of large parts of South Vietnam, with thousands of tons of explosivesâmore bombs than were dropped by all sides during World War II. Through America's largely compliant media, top Pentagon and White House officials assured the nation that even with support from the Soviet Union and Red China, a country as small and resource-poor as North Vietnam could not prosecute war on this scale much longer.

Then came Tet, a national and regional celebration of the Chinese lunar new year. Until 1968, in the course of this war, Tet was a brief midwinter pause for an informal countrywide truce. Tet 1968 was instead a surprise surge of simultaneous, well-coordinated, and deadly Viet Cong attacks on every major city in South Vietnam. Tet was a shock to America's nervous system, a blow to the national solar plexus.

From a purely military perspective, however, the Tet Offensive was a Viet Cong disaster. The nationwide civilian uprising against American forces that the VC had expected to trigger died stillborn. Fighting in some cities persisted for months; when it was over, most of the best VC troops, and virtually all its experienced leaders, were dead.

In addition, and not least, the usually lethargic Army of the Republic

of [South] Vietnam, the ARVN, which bore the brunt of Tet's urban fighting, acquitted itself with surprising distinction: “Initially outnumbered and under fierce attack, the ARVN closed ranks and fought,” wrote General Nguyen Cao Ky, then vice president, and a former commander of the South Vietnam Air Force (VNAF). “From the top down, senior officers led by example, sharing the risks of battle . . . We kicked the VC out of our cities, we kicked their ass. The little Vietnamese soldier will fight hard under good leadership.”

1

Tet was nevertheless a huge propaganda victory for the Hanoi regime. It told the American public that the Pentagon's rosy predictions of imminent victory were at best wishful thinking but possibly a campaign of deliberate deception. Millions of Americans held a personal stake in the warâthose who had served in Vietnam and those at or near draft age who could expect to be called up, as well as their families and loved ones. After Tet, a large and noisy proportion of these citizens demanded an end to the war.

The public relations disaster of the Tet Offensive forced President Lyndon Johnson to abandon his quest for a second full term. It helped to enable former vice president Richard M. Nixon to win the White House on a fuzzy platform that included a “secret plan” to end the war.

Soon after his inauguration in January 1969, Nixon revealed this plan: Under “Vietnamization,” the ARVN, whose petite soldiers struggled with large, heavy, obsolete American weapons left over from World War II, was to be equipped with the same weaponry as US units. ARVN was then to gradually take over the ground war. America would fund a rapid expansion of the VNAF, and provide air, artillery, and logistical support to the ARVN. As they engaged the enemy, America would disengage.

By late 1969, most of the million-man ARVN was equipped with lightweight, modern infantry weapons, supported by American and VNAF airpower and an enormous collection of US artillery, and sustained by a generous and efficient US logistics system.

An impatient White House now demanded that ARVN demonstrate the commander in chief's wisdom: South Vietnamese units must start to take the lead in ground combat. They must fight and win battles. Americans were expected to do everything in their power to help make that happen.

If that was Washington's view of things, it was not necessarily what the Saigon leadership, singular and plural, might have wished for. And it was not necessarily realistic: For one thing, the easy familiarity that American officers and senior noncoms had with complex, combined-arms operations, with coordinating the movement of men and machinesâtanks, artillery, aircraftâthrough four dimensions of time and space while dealing with complex logistics, as well as making full use of the capabilities of helicopters, represented skills that few ARVN officers had acquired, particularly at the company and battalion levels, where they were most needed. Moreover, virtually every man in every US combat unit could read and write and was hands-on familiar with machinery; the typical ARVN soldier was a peasant with fewer than five years of schooling and little experience with machinery, much less the complex apparatus of modern warfare. After 1969, it was not unusual to hear of ARVN artillery shelling its own troops, or of a VNAF strike on friendlies or civilians. Exhibit One: Associated Press photographer Nick Ut's horrifying photograph of nine-year-old Phan Thi Kim Phuc running naked from a VNAF napalm strike on her village. And that was in 1972.

ARVN also lacked an effective logistical system, and much of the war material provided by the US was siphoned off through a web of graft. ARVN troops in the field were often expected to forage for their own food, a huge distraction and an unwanted burden that did not endear them to the local populace.

While these obstacles could be overcome with time and patience, both were in as short supply in the White House as in the Pentagon.

Not incidentally, ARVN's generals and colonels realized that the departure of US forces would dam the Niagara of American cashâbillions every monthâflowing into South Vietnam's war economy, much of which trickled into their own pockets. They therefore sought to find ways to postpone the day when that river ran dry.

Just as unwelcome in Saigon was the fact that taking over the ground war inevitably meant many more ARVN casualties, which from the beginning of the war had been anathema to its commanders. This was, and still is, hard for Americans to accept: By the end of 1969, upwards of 220 GIs were zipped into body bags every week. Americans served one-year tours, however, while ARVN's troops remained in uniform until they were killed, horribly maimed, or too old to fight. And America's population was a dozen times the size of South Vietnam's 16 million people.

Moreover, despite the influx of new weapons and hardware, despite advisers, training programs, and the demonstrated capacity of properly led Vietnamese soldiers to fight well, many ARVN units were even less than what they seemed.

According to General Nguyen Cao Ky, as many as 10 percent, and in infantry units, even more, of the ARVN's rank and file were “ghost soldiers,” young men whose well-to-do families bribed a senior commander to report them present for duty while they were in fact happily elsewhere. Legions of these young draft dodgers, dubbed Saigon Cowboys, roamed the capital mounted on new Japanese motorbikes, noisily peddling black-market goods, illicit drugs, and prostitutes, mostly to Americans. Other draft dodgers worked in family businesses. Thousands lived or studied abroad.

Ghost soldiers' salaries disappeared into their commander's pocket; he also sold their rations, uniforms, and sometimes even their weapons. Regimental and battalion commanders knew that any period of protracted combat would reveal the hollowness of their formations. They therefore avoided it.

Americans advising senior ARVN commanders were not blind to their shortcomings. They were well versed in the commanders' personal idiosyncrasies, of their eagerness for battle or their aversion to it, and of their units' combat capabilities. These advisers, however, were also keenly aware of their commander in chief's desire that Vietnamization show results: ARVN battlefield victories. Most of all, these regimental and division advisers, US Army officers in the crucial middle years of their careers, knew that if reports that they sent up their chain of command described the commander whom they advised, the officer they had been sent to educate while

enhancing his unit's combat effectiveness, as cowardly, or corrupt, or thickheaded, or as someone who displayed little regard for troop welfare, or was reckless and mistaken in his choice of tacticsâif they painted a picture of ARVN cowardice or ineptness, they were likely to be replaced by an adviser who wrote more optimistic reports, to the detriment of their own career.

So the White House demanded ARVN victories, ARVN generals promised that battlefield success was around the corner, and US advisers pretended to believe them.

As for me, until the previous year, when I was stationed in nearby Thailand, I would have been pressed to find Vietnam on a world map. All that I knew of this war was that America was fighting Communists, and it was my duty to help my country. At age 21, I believed that I was seven feet tall, bulletproof, invisible when needed, and that Vietnam was to be the greatest adventure I could ever hope for.

I had had three years' service but not a minute in combat. My troops were very youngâmany still in their teens. Like me, most had enlisted or been drafted straight out of high school. A few had several months of combat under their belts, but even they could not have been prepared for what awaited us in late October 1969.

And so we went more or less happily onto the isolated hilltop called Kate, ignorant of the misaligned forces that controlled our fate, never expecting a bloody five-day monsoon of steel and fire, and entirely unaware that the ARVN generals responsible for our lives loathed and feared the mountain tribesmen on whom we relied to defend us and our isolated hilltop from the fierce and relentless PAVN infantry.

This is how it went, to the best of our recollections.