Ace of Spies (16 page)

Richard Spence has speculated that Reilly’s hidden hand was behind the explosion, as DuPont had opted to do business with Pierpont Morgan rather than Reilly.

16

Spence believes that German saboteur Kurt Jahnke executed the deed on Reilly’s instructions, drawing attention to Jahnke’s supposed later admission to his German superiors that he was responsible. The more likely scenario was that Jahnke was seeking to take credit for something that was none of his doing, and was, in all likelihood, a complete accident. Indeed, the official verdict remains, in the absence of any compelling evidence to the contrary, that it was an accident. According to former DuPont employees, explosions at the DuPont Works were not unusual. They did not happen often, but when they did they were usually due to accidental causes.

Furthermore, Reilly had been in America for less than three weeks when the explosion occurred. It would have been somewhat difficult for him to have sought a powder contract with DuPont, to have been rebuffed by the company, and then to have planned and executed such a response, all within the space of some nineteen days. In short, there is no tangible evidence to connect Reilly with either Jahnke or this tragic accident.

Since his departure from St Raphael back in July 1914, Reilly and Nadezhda had been exchanging letters. Her divorce, which had recently been granted, meant that they could now marry. Although there is no doubt that she was in love with him and that he was very fond of her, doubt remains as to whether he actually wished

to marry her. Although in his letters to her he promised to send for her as soon as he arrived in New York, she could well have had reason to doubt him. The fact that throughout their three-year relationship she had been married and latterly awaiting a divorce meant that the issue of marriage had not been a consideration. Once the divorce came through in 1914, he may well have had second thoughts, being perfectly content for her to remain as his mistress. If this was not the case and he really did have every intention of marrying her, there would have been absolutely no need for the Machiavellian scheme Nadezhda now embarked upon.

At her own expense she purchased a ticket in the name of Nadine Zalessky at Le Havre and took the SS

Rochambeau

to New York. As the liner neared New York she cabled Reilly to notify him of her arrival in order that he might meet her at the pier. She also cabled the New York police, informing them that Reilly was importing a woman into the state for immoral purposes – a criminal offence under the Mann Act.

17

When her ship docked on 15 February,

18

Reilly was there to meet her and so too were the police. The police arrested Reilly and, despite his insistence that she was his fiancée, informed him that he could only avoid prosecution and possible imprisonment if he married her immediately. As he had already promised to marry her and she had stated that this was the purpose of her journey, he did not have a leg to stand on. It was the first day of Lent under the Orthodox calendar, however, and Orthodox weddings do not, by custom, take place during the first week of Lent. Reilly, therefore, had to appeal to the head of the Russian Orthodox Church in America, Metropolitan Platon, to give special dispensation for the wedding to take place.

19

As luck would have it, for Nadine at any rate, Platon gave his permission, and the wedding took place the next day at St Nicholas’s Cathedral in Manhattan.

20

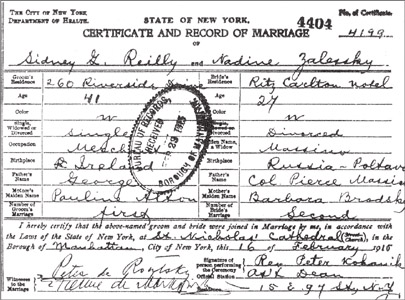

Nadine claimed in the marriage register that she was the twenty-seven-year-old daughter of Pierre and Barbara Massino, residing at the Ritz Carlton Hotel, at 313 East 63rd Street. She was, in fact, twenty-nine years

old. Reilly stated that he was a forty-one-year-old bachelor, the son of George and Pauline Reilly of Clonmel, Ireland, residing at 260 Riverside Drive, an address that did not exist until 1925. Petr Rutskii from the Russian Consulate was one of the witnesses.

Reilly’s marriage on 16 February 1915 almost certainly saved him from arrest by the New York Police Department.

G.L. Owen

21

believes that the Reillys left New York shortly after their wedding and undertook a visit to Petrograd. The timing of this visit may seem incidental, but it is of crucial importance in terms of authenticating a claim by Owen that the Reillys sailed back to New York on the same ship as a prominent German spy. Franz Von Rintelen was sent to America by German intelligence to co-ordinate a campaign of sabotage and disruption that would hopefully stem the flow of munitions to the Allies. Von Rintelen arrived in New York on 3 April aboard the SS

Kristianiafjord,

travelling on a Swiss passport under the name of Emil V. Gasche.

22

A search of the passenger list, however, reveals no Sidney or Nadine Reilly on board, nor indeed any male passenger fitting

Reilly’s general physical description (around 5ft 9 or 10ins tall, brown eyes, dark hair, in the region of forty years of age). This is purely and simply because the Reillys had been in New York all the time. They did not, in fact, leave the city until 27 April, when they boarded the SS

Kursk

bound for Archangel.

23

Arriving in the north Russian port on 11 May, they proceeded immediately to Petrograd. While Nadine spent some time with her family, Reilly entered into negotiations with the Russian Red Cross, with a view to securing, on their behalf, ambulances and auto-mobiles from Newman Erb and the Haskell and Barker Car companies.

24

He also met with the Tsar’s cousin, Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich. The grand duke had been head of the Directorate of Commercial Navigation and Ports during the war, and worked closely with Ginsburg in organising coal supplies to Vladivostok. A keen photography enthusiast, Alexander Mikhailovich was no doubt much impressed by the American automatic camera Reilly brought with him.

25

According to G.L. Owen, the Reillys were in Petrograd between June/July and September of 1915, a view shared by Richard Spence.

26

Although originally intending to leave Archangel on 13 June,

27

their departure was postponed until 26 June, when they headed back on board the SS

Czar.

The delayed departure was more than likely caused by the attentions of the Ochrana, who were taking a close interest in Reilly and the war materials he was trading in. Before going aboard the SS

Czar,

he was searched on the orders of Col. Globachev, head of the St Petersburg Ochrana. Nothing incriminating was found on him or in his trunks and he was allowed to proceed on his way.

28

One such deal that attracted Globachev’s interest concerned a consignment of nickel ore ordered through Reilly by the Russian government. The consignment was duly shipped to Russia via Sweden in a deal Reilly brokered through the Swedish Russo-Asiatic Company. All had proceeded smoothly until a routine check indicated that the weight of the ore unloaded in Petrograd was somewhat less than the amount loaded in New York.

29

This immediately lead to rumours that the missing

ore had been appropriated in Sweden and sold on to Germany. A more likely scenario, however, was that the Russian government had been short-changed in New York by a sleight of hand on the paperwork. It would not have been the first time that a Reilly consignment was loaded underweight but the customer invoiced for the full cargo.

Reilly’s postponed departure lead to a rumour reaching the Russian General Staff that the Ochrana had detained him. Maj.-Gen. Leontyev of the Quartermaster-General’s Office immediately sent a cable on 24 June

30

to the staff of the commander-in-chief of the 6th Army, instructing that urgent enquiries be made to establish what had happened to Reilly. In a reply from Maj.-Gen. Bazhenov, Leontyev was assured that Reilly had not been detained and that he had been allowed to depart unhindered.

31

Arriving in New York on 10 July,

32

Reilly returned to his desk at 120 Broadway. It did not take him long to work out that the main problem being encountered by American companies was not in securing munitions contracts

per se,

but in ensuring that the order, once manufactured, was actually accepted on delivery. Russian inspectors, whose job it was to ensure that shells, for example, were up to standard, were exceptionally careful about passing them. In the first six months of the war it was found, to the great cost of those at the battlefront, that some shell deliveries were not compatible with Russian guns and could not be fired. The result of this was a more vigorous system of quality control. This inspection system applied to all munitions including rifles, which had to be specially converted to take Russian cartridges. This presented an opportunity for Reilly, who had a close relationship with those issuing the surety bonds necessary before the Russian government would accept the consignment. On 19 April 1915, for example, Reilly signed a deal whereby he would, ‘assist in the performance of the said contract and in particular in reaching an understanding with the Russian Government as to the assurances required… that the contract will be performed’.

33

In other words, Remington

Union would pay Reilly a large sum of money to ensure that their rifles successfully passed through the quality control process and were accepted by the Russian government. Over three years later, Samuel Prior, who had signed the agreement with Reilly on behalf of the Remington Union Company, quite accurately described the deal as a ‘hold-up’

34

on Reilly’s part, for unless he was given a commission on the deal, the implication was that he would use his influence to frustrate their ability to get the rifles accepted.

In late 1915 the Russian government sent an official purchasing supply committee to New York headed by Gen. A.V. Sapozhnikov, another old Reilly acquaintance from St Petersburg. Whilst the committee was an understandable attempt to rationalise Russia’s munitions purchases in America, it was dogged with scandal almost from the day its members arrived. Although, as usual, Reilly had a personal motive for writing to Lt-Gen. Eduard Germonius on 21 December 1915, he was essentially correct in drawing attention to the disorganised and over-optimistic state of affairs concerning Russian munitions purchases in America. In his report he stated that:

In the last eight months the chief Artillery Administration in Petrograd and the Russian Artillery Commission in America have been holding talks with dozens of factories and endless different suppliers, banks, ‘groups’ or just ‘representatives’ about ordering from them 1,000,000 to 2,000,000 rifles and corresponding quantity of cartridges. The offers exceeded the demand many times over and if they were all added up it would appear that in these eight months Russia has been offered rifles and cartridges in quantities that may be expressed only in ‘astronomical’ figures. Understandably, there is nothing surprising about the fact that so many offers have been forthcoming: the example of Allison, who secured a contract for shells worth $86,000,000 is still fresh in everybody’s memory. What one cannot understand is that all these offers have been examined in detail, thorough talks have taken place, a huge amount of time and money has been spent on

correspondence and telegrams, inspectors have been ordered to look round factories, legal consultants have been given the job of drawing up contracts, in many cases draft, preliminary or even final agreements have been signed (and then torn up) – but these orders for rifles and cartridges have still not been placed.

The reason for this is that the Chief Artillery Administration does not know enough about the real state of the rifle and cartridge trade in America. Petrograd, as optimistic as the entrepreneurs themselves, is not giving up and continues to hunt for the grain of corn in all the paper-litter put out by Jones, Hough, Zeretelli, Morny, Wilsey, Bradley, Garland, Empire Rifle Company, American Arms Company, Atlantic Rifle Company et al., and is evidently ignoring the actual state of affairs.

35

Reilly went on to draw attention to the fact that the allied countries had placed orders in America for approximately 7.5 million rifles, 3,500 million cartridges and about 1.5 million gun barrels. His conclusion was that in their haste to take advantage of these large Russian contracts, many American firms had seriously overreached themselves and were highly unlikely to be able to deliver on schedule.

This eventually turned out to be the case, although the situation was not helped by the over-enthusiastic quality-control system. Before too long the system began to have serious repercussions on Russia’s ability to fight the war. The problem now was not the quality of the munitions they were receiving, but the fact that the inspection system was slowing the delivery process down to such an extent that the Russian Army at the battlefront was virtually out of shells to fire at the enemy. When Gen. Germonius became head of the Russian Purchasing Commission in America, this issue was one that was very much to the fore.

Again, Reilly saw a golden opportunity to exploit this opportunity. According to Vladimir Krymov he visited the plants that were contracted to manufacture shells and were experiencing difficulties in getting them passed, and proposed that in exchange

for a commission he could ensure that the inspectors would pass the finished munitions.

36

It is not surprising that the companies were initially sceptical to say the least, as he was not the first person who had approached them with this proposal. He told the companies, however, that he and Gen. Germonius were related and that through the general he could not only ensure the successful acceptance of their current orders but could also secure new orders for them. As proof he persuaded the managing directors of two companies to have lunch at the Coq d’Or, a country restaurant outside New York, and told them they would see him, his wife and Gen. Germonius having lunch together. The directors knew that Germonius never went anywhere, let alone had lunch with middlemen or suppliers. Nadine persuaded Germonius to have lunch with them at the Coq d’Or, and Reilly was thus able to show off the unsuspecting general to the directors. On 7 January 1916, an agreement was signed between Reilly and Samuel M. Vauclain, John T. Sykes and Andrew Fletcher on behalf of the Eddystone Ammunition Corporation. The agreement gave Reilly 25 cents commission on every round of three-inch shrapnel shell that was accepted.

37