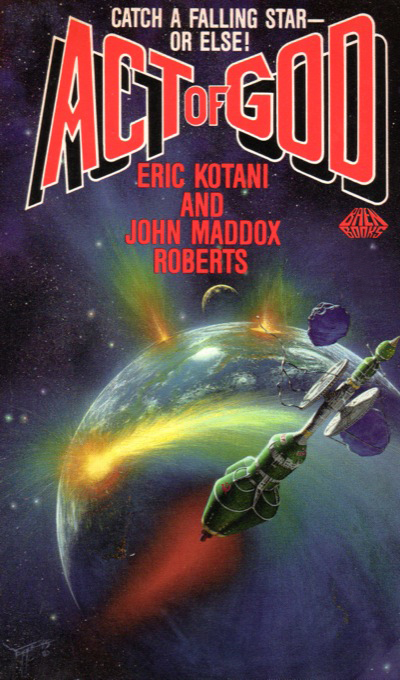

Act of God

Authors: Eric Kotani,John Maddox Roberts

Tags: #Fiction, #Science Fiction, #General

- PROLOGUE

- CHAPTER ONE

- CHAPTER TWO

- CHAPTER THREE

- CHAPTER FOUR

- CHAPTER FIVE

- CHAPTER SIX

- CHAPTER SEVEN

- CHAPTER EIGHT

- CHAPTER NINE

- CHAPTER TEN

- CHAPTER ELEVEN

- CHAPTER TWELVE

- CHAPTER THIRTEEN

- CHAPTER FOURTEEN

- CHAPTER FIFTEEN

- CHAPTER SIXTEEN

- CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

- CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

- CHAPTER NINETEEN

- CHAPTER TWENTY

- CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

- CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

- CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

- CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

- CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

- CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

ACT OF GOD

by

Eric Kotani and John Maddox Roberts

Island Worlds, #1

Soviet scientists discover the secret of a mysterious explosion that leveled a remote section of Siberia in 1889 and now intend to use their discovery to destroy the United States by identical, seemingly natural causes.

ACT OF GOD

This is a work of fiction. Ail the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 1985 by Eric Kotani and John Maddox Roberts

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form.

A Baen Book

Baen Enterprises

8-10 W. 36th Street

New York, N.Y. 10018

First printing, September 1985

ISBN: 0-671-55978-6

eISBN: 978-1-62579-227-3

Cover art by David Egge

Printed in the United States of America

Distributed by

SIMON & SCHUSTER

MASS MERCHANDISE SALES COMPANY

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, N.Y. 10020

To Robert A. Heinlein

PROLOGUE

TUNGUSKA REGION, SIBERIA

June 30, 1908

The Podkamennaya Tunguska River lies in the Central Siberian Upland, a vast region of low mountains covered by pine forest, inhabited largely by reindeer and a few nomadic tribes of hunters and herdsmen. It is one of the remotest, least-inhabited places on Earth. On this June morning of 1908, it is a part of the vast domain of Tsar Nicholas II, although he has little use for it, nor has anybody else, save those who hunt and trap and follow the reindeer. To the south lies the Verkhnaya Tunguska River, which flows from Lake Baikal. To the north is the Nizhnyaya Tunguska River, which throws a loop to the south completely around the valley of the Podkamennaya Tunguska. All three rivers flow into the Yenisey River, which flows north into the Kara Sea, far north of the Arctic Circle. The land is vast and unchanging. But on this June morning, something extraordinary happens, and it happens with extraordinary suddenness.

Reindeer start in panic and primitive men gaze up in fear and wonder as the clear vault of the sky is bisected by the searing path of an immense fireball. Moments later the sky is lit up by an enormous flash. The fireball is visible hundreds of kilometers away, though it endures only a few seconds, to be followed by a titanic shock wave.

Hundreds of kilometers to the south, a driver on the Trans-Siberian Railway thinks his boilers have exploded. When he stops the train passengers tell him of the flash they saw many seconds before from the windows. For hundreds of kilometers around the blast site, houses are shaken, windows are broken and people are knocked off their feet. The blast is registered in London, thousands of kilometers away.

Within hours, news of the mysterious event is telegraphed around the world. A meteorite fall is assumed and expeditions to the site are proposed. But mounting an expedition is no small endeavor; the Tsar is preoccupied with more important matters, and to the rest of the world central Siberia is less accessible than the remotest parts of Africa. Most of the year it is locked in winter of Arctic severity and accessible only briefly in spring and summer. Besides, there are many other matters of great scientific interest afoot in 1908, and while a large meteorite strike is interesting, it is hardly unique.

Gradually, Siberian nomads emerge from the area, with strange tales of forests laid flat and herds of reindeer slain. Miraculously, it seems that not a single human being has been killed or even injured by the blast. Much is made of this in later years. There are very few places on land where a blast of such magnitude could have taken place without the loss of a single human life.

Over the years, proposals for expeditions to find the Tunguska meteorite are proposed, but Russia is involved first in revolution, then in civil war. Not until 1927, nineteen years after the event, does an expedition penetrate into the remote region. What they find is unbelievable. Even after nearly two decades the forests remain flattened, the trunks of the trees radiating from the center of the blast like spokes of a wheel. The magnitude of the blast that caused such destruction staggers the imagination. At the center of this devastation must lie a giant crater.

There is no crater. Instead, at the very center, trees still stand. They are stripped of branches and foliage and much of their bark, but they still stand. Perhaps the giant meteor broke up just before striking; a search is made for smaller craters. Many small depressions are found but they turn out to be a natural phenomenon of the region, unrelated to the blast. Later expeditions find tiny meteoric particles, nothing more. All of them together could not mass enough to account for more than the tiniest fraction of the colossal blast of 1908. The mystery seems unsolvable.

Over the years the Tunguska event becomes a favorite with the wilder fringes of science. With each discovery of physics, with each new fad of pseudo-science the event is reexamined, often with more enthusiasm than precision, and applied to the new sensation. At last A-bomb and H-bomb testing reveals the torus or "donut" effect of aerial nuclear blasts and it is recalled that the trees were still standing at the center of the Tunguska blast. The torus effect would cause just such a phenomenon. A natural H-bomb from space is speculated, although how such a natural bomb could be constituted is never satisfactorily explained.

The great UFO fad brings the suggestion that the engines of a damaged spaceship had exploded. Perhaps the controllers of the craft, knowing that it was doomed, steered it to a spot where it was unlikely humans would be harmed. The Arctic or an ocean seems an even better choice for a harmless blast, but the idea remains attractive to enthusiasts.

Next, it is pointed out that the collision of a small particle of antimatter with the Earth's atmosphere might cause something resembling the Tunguska event. Where it came from, or how it survived the trip (the vacuum of space isn't quite a vacuum) is not explained.

Then the media are full of the black hole concept. The Tunguska event is unearthed again. Maybe the Earth collided with a black hole, a very small one. The super dense object went right through the planet, in at Siberia, making a hole too small to detect, out through the ocean on the other side. Why this would generate an aerial blast effect is not explained.

Except when under the influence of alcohol or whatever, responsible scientists refrain from such speculations. That the event occurred is beyond dispute, but scientists require reliable data in order to draw conclusions. The event is too long past, the recording instruments of the period too few, too primitive and too far away from the event. The eyewitness accounts differ radically, and every policeman knows how unreliable eyewitness accounts are even minutes after an event occurs. When the event witnessed is something outside human experience, eyewitness accounts are little better than useless. Until a similar event can be observed and properly quantified the Tunguska event will remain a mystery.

And so, until the final decade of the Twentieth Century, the Tunguska event remained.

CHAPTER ONE

TSIOLKOVSKY SPACE CENTER

KAZAKH REPUBLIC, U.S.S.R.

The automobile stopped before the administration building, its tires raising a small cloud of dust from the dirt road. A young man emerged from the vehicle and climbed the steps which still smelled of new-cut pine. At the top of the steps he turned and admired the view. The administration building stood on high ground, and below him stretched the still-growing expanse of roads and buildings that was the world's newest space center. Beyond the center was the Aral Sea, but the facility did not end at the shore. Gigantic piers crowned with gantries and spidery structures of steel and glass linked water and land. The sight filled him with awe. Something unprecedented was being done here. That was why the project was being carried out here, instead of at the old space center. He was proud to be a part of all this.

The young man turned and went inside. He had to walk carefully over the wrinkled cloths that covered the floor, littered with brushes and empty paint cans. The workmen who desultorily stroked the walls were short slit-eyed Uzbeks, brought across the Aral by boat. Like most of the laborers here, they had been chosen because they spoke no Russian and were illiterate in their own tongue. He walked to the desk that guarded the Director's door, where a strikingly handsome young woman sat. She looked up at his approach.

"Is the Director in?" he asked.

"Yes. What is your name and your business with the Director, please?" She had a lovely smile and a voice that took the edge off the dry, bureaucratic demands. He could not quite place her accent. Finnish? Lithuanian? From that area, he was sure. That fitted with her blonde good looks.

"Alexei Ilyich Kamarovsky. I'm here to take him to the air strip. There's a visitor arriving, you know."

"Ah," she said, "

that

visitor." She pushed a button on an intercom.

"Comrade Tarkovsky, a Comrade Kamarovsky to see you."

"Just a moment." The rumbling voice had a trace of the power that had made hundreds of students and subordinates quake.

"I haven't seen you here before," Alexei Ilyich said. "Are you the Director's new secretary?"

"No," she said, again with the dazzling smile. He noted that her teeth were rather large, but at least none of them were steel. None of the visible ones, in any case. He wasn't so sure about the molars. "I'm an astronomer. His usual secretary lives in my dorm. She's been sick all week and the rest of us have been standing in for her. Mostly, it's been me. I got here last month and found that the bureau where I'm supposed to work won't be ready to operate until October. Until then, I'm everybody's stand-in."

"Typical," Alexei said. Then he caught himself and looked about guiltily. Had anyone noticed his disloyal acknowledgement of official inefficiency? Probably not. It was the kind of thing everyone joked about, but not in front of strangers. He glanced at the Uzbeks. You never know.

"Where did you come in from?" he asked, to change the subject. "Lithuania?"

"Close," she said. "I'm from Mustvee, on Lake Peipus in Estonia." He tried to bring up a mental picture of the place, but all he could remember was something about Alexander Nevsky fighting the Teutonic Knights on the frozen lake. There had been a movie about it, once. He'd seen it on television. The music had been by Prokofiev.

"Send him in," said the rumbling voice.

"I'll see you later," Alexei said. He hoped that he would. She was the first remotely attractive woman he had seen since moving to this wilderness of Asiatics. He went through the still-unpainted door.

Even in this short time, the old man had managed to turn his office into a total wreck. The floor was littered with paper; books were stacked everywhere. Food scraps littered the desk and dishes and teacups overflowed with cigarette butts. In a corner stood an old-fashioned samovar. The massive man behind the desk wore an ill-fitting suit that was years out of date. His shaggy hair was still mostly black, white about the ears. The face was that of a bulldog who has been bashed across the nose with a hockey stick. He looked up from his slide rule. Despite the availability of Japanese calculators, Tarkovsky still preferred the slide rule. He had been known to win hundreds of rubles in bets with mathematicians who thought they could work out problems faster with one of the little Japanese miracles.

"Come in, Alyosha," Tarkovsky said. He had known Alexei's father for many years and could use the familiar form. "What do you want?"

"I think you know, Comrade Tarkovsky," Ivan said. Had the matter not been so serious, he would have addressed the director as "Pyotr Maximovich."

"Oh, sit down, Alyosha," Tarkovsky said. He opened a drawer and rummaged around until he found a bottle of vodka. "Here, have a drink." He poured a generous dollop into a none-too-clean teacup.

"Pyotr Maximovich," Alexei fumed impatiently, "I'm to take you to the air strip. We can't let our visitor land and wait for you."

"That's better," Tarkovsky said. The younger man refused to touch the cup so Tarkovsky drank it himself. "Visitor," he said, turning the innocent word into an obscenity appreciable only to another Russian. "Another damned politician down from Moscow. Do they think I have nothing better to do? Do they think my space city is—" he waved his hands expressively, searching for the word, "—what's that place in California, where Khrushchev wanted to go? Disneyland? Yes, do they think this is Disneyland and I am some kind of tour guide?"

Alexei winced slightly. He hoped there were no listening devices in the room. "This is a fairly high-powered politician we're to meet, Comrade Tarkovsky," Alexei reminded him.

Tarkovsky snorted. "Deputy Premier. How many of those have come and gone in my time? I can't keep count. How many men in the Soviet Union could hold that job? You could, Alyosha. One of those Tartars out there painting could. How many men could direct this project?"

Alexei sighed. "Only you, Pyotr Maximovich."

"Remember it. He'd better remember it, too." He tossed off the last of the vodka in the glass, dropped the bottle back in the drawer, shut the drawer. "Let's go meet this big shot," he said.

The automobile drove out the bumpy road past the docks, past the workers' housing, to the airship. There was a small airport building standing beneath the control tower. Most of what came here arrived by rail.

Tarkovsky got out of the car and stood with head hunched between his shoulders, hands in pockets. Both airstrip and sky were innocent of airmail. "Damned Moscow pimp," he muttered, "I knew he'd be late."

"Here it comes," Alexei said, hearing the engines of the Ilyushin. Tarkovsky's look brightened as the aircraft came into view, but not for the passenger, he admired the sleek lines of the new aircraft, an outrageously expensive supersonic transport designed to fly better, higher, faster than anything the Americans had.

"That's beautiful," he said. "That's worth the trip out here." The aircraft landed, tiny puffs of smoke rising from its tires. It braked, turned, and taxied to the building where Tarkovsky and Alexei wailed. By now, a number of other scientists and administrators had arrived to greet the great man. First to emerge from the Ilyushin was a tall, thin, bespectacled man with a shiny scalp.

"Look at him," Tarkovsky muttered so only Alexei could hear. "Head shaved slick as an Army recruit's. Maybe I'll address him as 'Comrade Private.' "

"Pyotr Maximovitch," Alexei said urgently, "if you have no respect for what he is, at least remember what he used to be."

Tarkovsky was silent. That was one thing he didn't want to think about. The new Deputy Premier of the Politburo who was walking toward him was Sergei Nekrasov, and Sergei Nekrasov was, until his promotion, head of the KGB.

"Comrade Director Tarkovsky?" Nekrasov asked, holding forth a hand.

"The same," Tarkovsky said. The hand he shook was firm and dry. Everything about Nekrasov seemed dry. His skin, his shiny scalp, his voice, even the eyeballs behind the thick spectacles looked dry. Behind Nekrasov were several faceless men, so featureless that Tarkovsky had trouble counting them. KGB, he thought.

"You honor us with your visit," Tarkovsky said. In spite of his contemptuous words to Alexei, he felt distinctly nervous in the Deputy Premier's presence. Even the greatest scientist had to acknowledge the supremacy of the KGB, which the Deputy Premier probably still ran, despite his change of title. "Will you allow me to show you our new facility?" Nekrasov and Tarkovsky got into the rear of the staff car. One of the faceless men got in beside the driver. The faceless man carried a briefcase, presumably Nekrasov's. Alexei was left behind to return with the others.

Tarkovsky pointed out all the features of the modern spaceport, beginning in a bored, tour-guide fashion, but growing more animated as the tour progressed, unable to repress his enthusiasm for the project. As much as any single man can accomplish anything in the Soviet Union, the Tsiolkovsky Space Center was

his

creation. Nekrasov nodded politely and asked pertinent questions, but it was clear that space science was not of great interest to him, beyond its military applications. Tarkovsky wondered why the man had come.

At Nekrasov's direction, they drove out onto one of the piers and emerged from the car. Workmen nudged one another. Everyone recognized Tarkovsky, but who was the bald man? Somebody important, that was clear from the transportation and his fine, foreign-tailored suit. They tried to recall his face. Was it one they saw on the balcony over looking the May Day parades in Red Square? If so, it was too far down the left end of the lineup of notables to be remembered. They shrugged and went back to work.

Nekrasov kicked at the steel decking and sniffed the fresh breeze off the Aral. The big piers enclosed wide basins. "It looks more like a naval base than a space facility." He looked up. The sky was clear, with some cumulus clouds massing on the southern horizon. "I wonder what the Americans are making of all this? They must have plenty of satellite pictures by now."

"If one just passed overhead," Tarkovsky said, "some American will be studying your expression this evening. Their high-resolution cameras are that sensitive. We got orders just last week not to let any sensitive documents be exposed to aerial surveillance. Personally, I don't believe their cameras are that good, but one never knows."

"The order came from my office," Nekrasov said.

Tarkovsky's shaggy eyebrows went up a trifle. Security orders for his project emanating from the Deputy Premier's office? That sounded ominous. This was no routine visit. He knew he was about to hear some bad news.

"Let's take a walk," Nekrasov said. He set out toward the end of the pier, nearly a third of a kilometer out over the sea. Behind them, the brief-cased KGB man trailed at a discreet distance. As he walked, Nekrasov made polite conversation and Tarkovsky was aware that every word was loaded.

"I've been keeping current with your end of Project Peter the Great, Comrade Tarkovsky. I'm very keen on the space sciences, you see." Tarkovsky knew this to be a falsehood but he let it pass. Like most such men, Nekrasov was an ignoramus in everything except power.

"Project Peter the Great is just one of many we shall be carrying out at this facility, Comrade Nekrasov, although I admit it's my pet. Since you have been studying it, you realize there are many experiments I wished to have included in it, but the budget—"

"I wish to speak to you about that." Nekrasov stared out at the piling clouds to the south as if trying to forecast the weather. He nodded to the KGB man and was handed the briefcase. The faceless man backed away out of hearing range. Nekrasov reached into the briefcase and withdrew a sheaf of papers. Tarkovsky recognized the title. It was one of his own scientific papers, but it now bore a security stamp above the title that had never been there before.

"Two years ago," Nekrasov continued, "this paper was brought to my attention. Do you recognize it?"

"My paper concerning the Tunguska event," Tarkovsky said. He wondered which of his colleagues had shown Nekrasov the paper. Probably no friend of his. His sense of foreboding increased.

"A most fascinating document, Comrade. Its implications struck me immediately. I have also read your complete, original proposal for Project Peter the Great. Far too grandiose, I was told, far too expensive."

Tarkovsky shrugged, hands in pockets. "It's how these projects work the world over. One proposes the optimum in hopes of receiving the minimum."

"Short-sighted fools," Nekrasov said. "They couldn't see what this means. Comrade Tarkovsky, from now on, my office is in full charge of Project Peter the Great. All results will be reported directly to me." Tarkovsky was stunned, but he was well-schooled in hiding such things. Nekrasov continued: "You will receive the fullest possible funding to carry out your project as first proposed."

"Comrade Nekrasov," Tarkovsky pointed out, "this will mean stripping half the projects in our entire space program."

"Just send your requests through my office," Nekrasov said. "If your colleagues have any complaints, they may address them to me." An oblique way of saying that there would be no complaints. "As of now, this project has Class One priority, right along with our missile defenses. It is also under maximum security." He took several more papers from the briefcase and handed them to Tarkovsky. "Here are the names of persons you have here who are no longer to work on the project. All of them are security risks."

Tarkovsky scanned the list. "But these are eminently qualified personnel, Comrade," he protested. "Some of them I have worked with for years. I am not sure I can carry out the project without them."

"Nonsense," Nekrasov said, coldly. "Your field is space science, Comrade Tarkovsky. Leave state security to me." A not-so-oblique reminder of his former position. "Dismiss these people. Other positions, less sensitive, will be found for them. Then send me a list of persons to replace them. Make it a long list, with at least three hundred percent redundancy factor. Many of those you propose will also have to be vetoed for security reasons."