Afterlands (47 page)

LAST VERSIONS

I

N OCTOBER

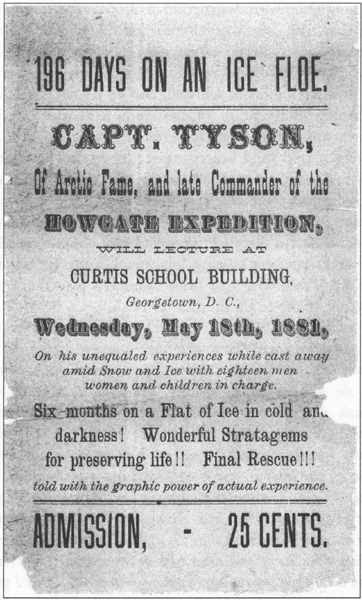

1906, after a summer of ill-health, George E. Tyson died in his home on H Street in Washington. For some time he had suffered from heart problems. Obituaries, such as the large, respectful one that appeared the next day in the

Washington Post

, attributed his problems to the wound he had received aboard the

Florence

twenty-eight years before. He was survived by his wife Laura and their three grown children, as well as by his first wife Emmaline and their son, George E. Tyson Jr., then thirty-five years old and living in Porthill, Idaho, a small town on the British Columbia border. Soon after the funeral, George Jr. wrote to his mother in Brooklyn. By then he had been estranged from his father for almost twenty-five years.

Dear Mother:

The article that you sent giving the account of father’s death I did not open until I reached home. In the solitude of my cabin, I read the news of father’s death. And when I saw his picture, I noted his face wrinkled with age through the lapse of all these weary years. Then I thought of all the suffering he must have endured during the long Arctic night, starving and freezing. He caused us many a pang, Mother, he caused us many a pang, but he was my father

,

and the news of his death saddened my heart. I often think that the awful hardships he endured affected his mind and caused his heart to wither. The love I bore him when a baby boy, awoke again to life. And I wonder if he ever thought of his boy through the last

20

years or did he go down to his grave and never a word of me? Poor father, for you I shed tears both of pity and of love. Seek his grave, Mother dear, and place some flowers there for me. And let your loving radiance glow around the place. It was noble of you to forgive him. You are a good mother and I love you, and am proud of you. He is gone now, gone forever. He is forgiven. Let us remember him as he was when his smile was long and his voice was soft and tender. Let us ever cherish in our hearts his loving memory. Peace to his ashes. He bore an honoured name. May it never perish

.

Your loving son, George

Tyson was buried in the Glenwood Cemetery in Washington, D.C. But this was not the end of his reputation. As late as 1976—although no later—his name and a biographical synopsis appeared in the massive

Webster’s Biographical Dictionary:

Tyson, George Emory, 1829–1906. Am. arc. Whaler, b. Red Bank, N.J.; member of Polaris arctic ex. under C.F. Hall; assumed command of a group, 19 in all, accidentally left adrift on an ice floe (Oct. 15, 1872–Apr. 30, 1873) and by resourcefulness and seamanship kept up morale of members of the party until they were rescued, after drifting about 1800 miles, by a sealer off Labrador.

Some years after Punnie’s and Tukulito’s deaths, a Groton woman named Mary Walker Raymond, one of Punnie’s former classmates, wrote briefly of her friend in an unpublished memoir:

She was a good little playmate, and with her broad, brown face, black, shining eyes, and very straight, black hair, with her little fur suit and cap with hanging tails, she makes a pleasant picture in my chamber of memories. Julia, my sister, and I, New Englanders for many generations, taught to conceal our feelings, could never quite understand the long, clinging kiss with which Hannah let her go from the gate in the morning, or the rapturous way in which she was caught up in her mother’s arms again at night, to receive many more kisses…

.

On Punnie’s small headstone, under the particulars of her name (which was in fact Silvia Grinnell Ebierbing, although the name was used only at school and on legal documents) and her place and time of birth and death, there is a partially legible inscription. In March of 2002, I knelt in front of the stone, and with a charcoal stick and a sheet of paper torn from a notebook I did some very amateur rubbings. A number of the words eluded me. The American writer Sheila Nickerson, who must have been there only a year or two before I was, researching a non-fiction book about Tukulito, did better with her own rubbings and has made an effort to recreate the full inscription, including the badly faded last line—a process not unlike translating almost inaudible words from an old recording, in a difficult tongue.

She was a survivor of the Polaris Expedition under Commander Charles Francis Hall, and was picked up with 19 others

[sic]

from an ice floe April 30, 1873, after a drift on the ice for a period of one hundred and ninety days and a distance of over twelve hundred miles. Of such is the kingdom of

The last word remains unclear. I think this is right; I think I prefer it blank, uninterpreted, the beloved child and her mother still alive in the silences. Nickerson remarks that she wanted the word to be love, thought it might be, but couldn’t be certain. Heaven, she thought, was another possibility. But she wanted it to be love.

Of Roland Kruger and the Sina people, nothing more is known.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Concerning the passages from Tyson’s

Arctic Experiences

(Harper & Brothers, 1874; republished in 2002 by Cooper Square Press, with a new introduction by Edward E. Leslie)—while I often quote Tyson’s published words verbatim, I have also excised, rearranged, conflated, compressed, and occasionally invented, always following the demands of my story as it grew and pursued its own inherent drift. Likewise, the italicized journal entries, or “field-notes,” are inspired by what survives of Tyson’s field-notes, although here too—here especially—I have improvised according to my needs, while at the same time maintaining the consistent differences, in both tone and content, between Tyson’s actual notes and the corresponding passages in

Arctic Experiences

.

Of the real Kruger, little is known. In

Arctic Experiences

Tyson portrays him as a prime troublemaker and mutineer, but elsewhere cites him as one of the few men volunteering to help at moments of extreme danger. From this intriguing contradiction his character emerged—independent, defiant, courageous. His and Tukulito’s stories on the ice are largely improvised in the rifts and openings in Tyson’s own, sometimes unreliable, account, while Kruger’s afterstory—unlike Tyson’s and Tukulito’s—springs purely from my own imaginary pursuit.

In the concluding “Last Versions,” all material is quoted verbatim.

A note about some of the names. A modern, more accurate spelling of Tukulito’s name would be Taqulittuq, or else Tuqulirtuq, while Ebierbing is now usually spelled Ipirvik. For the purposes of this book I’ve retained the nineteenth-century spellings—spellings that Tukulito herself used when writing the names. As for Punnie, the name is a corruption of

panik

, the Inuktitut word for “daughter.” English speakers, hearing Tukulito and Ebierbing address their daughter in conventional Inuit fashion as

panik

, assumed at first that it was a name, and spelled it “Punnie.” For convenience, the child’s parents came to use the word as though it was a name when referring to her in the presence of whites.

The German name Kruger would normally take an umlaut over the “u,” but Roland Kruger, like other immigrants to the New World, jettisoned that stigma upon arrival.

Of the many to whom I owe thanks, I want to single out those who read all or parts of this book in draft form—Kendall Anderson, Tim Conley, Heather Frise, John Heighton, Stephen Henighan, Michael Holmes, John Metcalf, Anne McDermid, Michael Redhill, Ingrid Ruthig, Alexander Scala, and Rhoda Ungalaq and John Maurice—as well as those who generously gave advice or information on various matters: Erica Avery, Judith Cowan, Marty Crapper, Jennifer Duncan, Rupert Hanson, Deirdre Molina, Adrienne Phillips, Scott Richardson, Leah Springate, John Sweet, Bill Staples, Roland and Bettina Speicher, Anje and Nico Troje, and Michael Winter. I was also lucky to have Doris Cowan as copy-editor again.

I must thank my terrific editors—Michael Schellenberg and Louise Dennys at Knopf Canada—for their various astute interventions. I’m also very grateful to Anton Mueller at Houghton Mifflin and Simon Prosser at Hamish Hamilton. Likewise my agent, Anne McDermid, as well as her associates, Jane Warren and Rebecca Weinfeld—thank you so much for your help.

I’m grateful to Douglas Glover for choosing an excerpt from this book (pages 31–38) for

Best Canadian Stories 2004

. Also to Sheila Nickerson, whose carefully researched and moving biography

Midnight to the North

will interest any readers who wish to know more about Tukulito/Hannah. Bruce Henderson’s

Fatal North

was also helpful, in part by directing me to material contained among the Captain George E. Tyson Papers, at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

I’d also like to acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts; the Ontario Arts Council; the Concordia University English department, which gave me a writer-in-residence position during the 2002–03 school year; Master John Fraser and Massey College, for doing the same for me in the winter of 2004; the Hawthornden Foundation, for a three-week stay at Hawthornden in 2003; and the Pierre Berton House Foundation, whom I thank for a brief but inspiring residency in Dawson City in 2001.

And of course, my first reader, Mary Huggard.

This book is for the Scalas.

S

TEVEN

H

EIGHTON’S

first novel was the critically acclaimed bestseller

The Shadow Boxer

, which went on to be published in five countries. He has written two short story collections,

Flight Paths of the Emperor

and

On earth as it is

, along with four poetry collections, including

The Address Book, The Ecstasy of Skeptics

, and

Stalin’s Carnival

. His work has been translated into a number of languages, has been nominated for the Governor General’s Literary Award, the Trillium Award, the Journey Prize, the Pushcart Prize, and Britain’s WH Smith Award, and has received the Air Canada Prize, Gold Medals for fiction and for poetry in the National Magazine Awards, the Gerald Lampert Award, and the Petra Kenney Prize.

Afterlands

has been published in the United States, Britain, Australia, Germany, and the Netherlands. Steven Heighton lives in Kingston, Ontario.