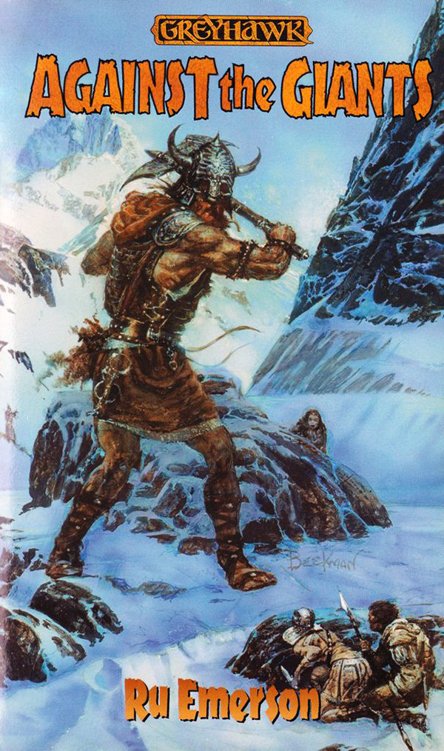

Against the Giants

GREYHAWK

AGAINST

THE GIANTS

Greyhawk - 01

Ru Emerson

(A Flandrel & Undead Scan v1.0)

The morning of 14 Harvester dawned muggy and too warm in the

remote Keoland hill village of Upper Haven. The newly risen sun cast a ruddy

pall over a crossroad just beyond the last huts as Yerik, the sturdily built,

gray-bearded village headman, emerged from the hut that he shared with his

mother. They had shared the small dwelling ever since his father and young wife

had died of fever twelve years earlier. His beloved Aleas had been heavy with

their first child, and the grief over their loss had hit him so that he hadn’t

wed again, taking the village as his family instead.

So far, Upper Haven’s year had not been a good one. The young

baron had died of fever the preceding winter, leaving no heir. Since his death,

there had been none of the usual hunting parties through the area. Baron

Hilgenbran, who had paid in silver for all supplies needed at his lodge—from

fowl and eggs for his table to wood for the enormous firepits—had been a stern

but fair ruler. Without him, there had not been the usual drain on Upper Haven’s

limited resources, but there had been no coin either.

The village’s chickens hadn’t increased properly, thanks to

the icy winter that had hung on well through Readying, and spring had been

unusually cold and wet, lasting well into planting season—in mourning for the

baron, some said. Whatever the cause, the grain hadn’t sprouted until nearly

mid-Wealsun, and some of it was still underground at summer’s longest day. By

this late date, the wheat and oats should have been threshed and stored in

watertight clay jugs down in the communal root cellars where they would keep the

winter.

Now, with the grain barely ripe, even the youngest farmer of

Upper Haven could look at that ruddy eastern sky and predict heavy rain by

nightfall.

“There’ll be lightning,” Yerik predicted gloomily, his eyes

fixed on the ruddy sky where the sun would soon rise, “and fires down where we

pasture the goats and horses. It was too wet all spring, and it’s been too dry

since.”

His mother stepped on to the small porch just behind him,

deftly working her long white hair into a thick plait. Gran seemingly had no

other name—at least none that the villagers could remember. Old as she was, her

memory was astonishingly sharp. She nodded. “Like the year—was it almost forty

years ago?—year 546, yes. A bad one, everything on-end. It was too wet all

summer, too dry in fall, and a poor harvest because of it. What grain there was

rotted when rain fell before we could reap.” She fastened the plait with a bit

of faded blue ribbon. “At least the rain put out the fires that year. And it’s

our good fortune that you were clever enough to call on High Haven to come in

and stay last night, should the grain be ready today.”

She glanced toward the low stable, usually empty this time of

year since the herds grazed out all year except snow season. At the moment, the

stable threshing floor was packed with High Haveners—twenty men from the upper

village, who would exchange labor now for flour and fodder come winter. Fifteen

young women who had come down from the mountain with them had taken over the

common house for the night.

Yerik sighed heavily. “The grain will

have

to be

ready. We’ve no choice.”

“Yes. The crop is your business today, son. Remember that if

we go hungry this winter, those who like placing blame will blame you. Worse

still, we’ll lose Bregya, and she is a fine tanner.”

The headman nodded. “We’d also lose her father. Digos has not

been well the entire year. A better b’lyka player we’ve never had.”

“True.” Gran flipped the braid over her shoulder and came

down the step to stand beside him. “Organize everyone able to help in some way.

The herders are a sturdy lot. They’ll give you good time, and old Haesk and his

brother can help keep watch over the babes. Get little Adisa to help Bregya tend

her small ones. Take blankets so they can sit under the trees and weave us

wreaths from the stems for good fortune. Make a game of it for the youngest. The

children are useful at finding all the loose wheat-heads, if you plan it right.”

Yerik nodded and smiled.

Gran patted his arm. “Yes. I see you remember the game I made

of it, when you were a small boy. Leave me Mibya and her sister. I’ll need them

to start pots of soup for everyone. We’ll eat together once the crop is safely

inside.”

“Good.” He rubbed his hoary beard and nodded. “That will free

up more of the women to help. The rain may hold off until middle night. It has

that look. Still, we’ll get the crop in as quickly as we can. Remember Lharis

and his son are out hunting. They should return with meat.”

“Should,” she agreed with a smile. “We won’t count on it,

though.”

“No, but old Mikati swears he saw an entire herd of deer on

the northeast plain two days ago. You know Lharis. If there’s a herd anywhere

near, he’ll bring in at least one.”

“I will count deer only when I can touch them,” Gran replied.

“I’d welcome meat, but if not, we’ll manage. We always do.” She gazed at the

eastern sky with visible misgivings. “I wish I liked the look of this morning

better.”

“You”—he eyed her sidelong—“

recall

a day like this?”

he asked tentatively, emphasizing the word that also meant accessing the oral

village history passed down to her, mother to daughter, wisewoman to apprentice,

for all the years Upper Haven had been a village.

She shrugged. “No. I’m merely worried. We know the weather

has been erratic all year, and it will play us foul if it can. Go, shoo.”

Yerik nodded absently. His eyes were fixed on the horizon,

and she doubted he’d heard her. “Do you see an omen?” he whispered.

“None of that!” she hissed. “They’ll not take it well—our

people

or

the highlanders—to hear you say ‘omen’! Keep everyone busy as

you can. The other women and I will bring midday food to you. Why”—she laughed

softly—“we’ll make a picnic of it, and then a holiday tonight, especially if

young Lhors and his father bring us game. Offer your reapers a proper

harvestfest, dancing and music and a feast, good barley and beet soup with

honeyed flat bread Filling stuff, even if there isn’t venison. A chance for the

young men of the highlands to properly meet our girls.”

“And the other way about.” Yerik smiled. His young wife had

come from High Haven at just such a small harvestfest. He patted his mother’s

cheek. “What will we do,” he murmured, “when you finally leave this world for a

better?”

She clasped his hand. “I do nothing special. I’m simply a

woman with long years and a good memory. The village does as much for me as I do

for the village—just as we keep an old warrior like Lharis happy by making him

huntsman for all of us and letting him teach his skills to our boys. I can still

cook, and I can see patterns that repeat over time.”

“You make it sound so… so ordinary,” he protested.

“It is ordinary, thank all the gods at once,” she assured

him. “Certain things occur, now and again—like a too-wet planting season.” She

released his hand. “Get everyone out there. We’ll bring black bread, apples, and

ale at midday.” Her gaze moved beyond him toward the sunrise, and she looked

briefly troubled. Before her son could question her though, she shook off the

mood and shooed him away.

Yerik straightened his tunic, settled the thick belt around

his middle, then strode off into the midst of the village, rapping on one door

and then another before he vanished into the stable to waken their visitors.

Gran watched him go, nodding approvingly. The harvest would

be in and safely dry before the storm hit. Nothing else mattered, except keeping

the morale of both villages high.

She drew a thread from the ragged hem of a sleeve and wound

it around her finger so that she would remember to have the common room readied

after the soup was simmering. There’d be no dancing in the open square

this

night—not for long, at least. The ache in her bones told her that this would be

the kind of storm her long-dead husband had called a giant killer.

An interesting name, she thought. Why it was called that,

however… She didn’t know for sure. Probably because it described a true

fury of a storm, a storm that hit just short of midnight and pulverized the

senses with forks of lightning and sent thunder to set the dogs howling and make

the elders glad their ears no longer worked so well.

After a full day under that hot, muggy sky, most of the

harvesters would be exhausted, only the young still willing to dance. With luck,

the worst of the storm wouldn’t hit until the children were sound asleep.

She’d best remember to tell Yerik to make sure a few of the

villagers had enough energy to patrol the fields. Lightning-fires could

devastate what few grazing lands they had.

She shoved the braid over her shoulders. Storm weather was

making her feel broody and old, but there was work to do. She glanced toward the

sunrise one last time before setting to her tasks. The sun had cleared the

distant peaks and now seemed merely a little too bright. West, the mountains

were still a dark mass, smothered in black towering cloud.

* * *

Out in the fields, the harvest went on as the sun rose to

midday and fell toward the ever-thickening cloud in the west. Women and men,

bent nearly in half, worked their way efficiently backward down the ranks of dry

plants, grabbing a fat handful of stems and scything them right at the dirt

before dropping them in place and moving on to the next handful. Behind them,

others came to free a single stalk and use it as a binding cord around the rest.

Boys and young women followed, gathering up the bundles and carrying them to the

two handcarts, while children picked up whatever had fallen and tossed it into

baskets.

Yerik allowed a decent break for midday meal, knowing people

would be able to work harder and longer for food and a short nap. The weather

still held off, but the late afternoon air was pale gold and utterly still, as

if some god had distilled it.

The sun was still a full hand above the clouds when the last

basket was picked up and the carts were hauled back under the stable’s low roof

for the night. Abandoning the carts and baskets, villagers and their guests went

to remove the layers of dust and chaff-coated sweat before gathering in the

village square where two black pots bubbled, spreading the soothing odor of a

familiar soup.

Night came early, with a rising wind and heavy black clouds

that blotted out the western mountains and even the near foothills. Thunder

grumbled in the distance, and occasionally the western sky was briefly pale with

lightning. But the air was cool and fresh for the first time in long hours, and

the rain held off.

After everyone had eaten well, Dikos broke out his

three-stringed b’lyka, while Mikati unpacked the four flat drums from their hide

case, settling them on his broad lap. People cheered and clapped as the two

consulted before finally breaking into the familiar jigging tune they always

played first. For some moments they played to an empty square while some of the

older women clapped time. Then Emyas tugged her newly pledged Arkos to his feet,

and got him dancing. Others joined them. A half dozen of the girls got up and

formed a circle, dancing, giggling at the boys and at each other. Gran and the

other cooks settled back, pleasantly tired, to watch and occasionally gossip

about the dancers or those who sat close together, chuckling as they wagered on

which would be the next pair to pledge.

Song followed song as evening deepened into night.

All at once, the air turned much cooler. Lightning forked

across the southwestern hill country and thunder rumbled, louder and closer to

the flash of light. The two players set aside their instruments as a gust of

wind blew across the ground, sending a swirl of dust and cook-fire smoke high.

At that moment, a dark, bulky man in leathers came into the open light, followed

closely by a youth of perhaps seventeen years. The older man carried a strung

bow in one hand and a drawn sword in the other—unusual in a peaceful village.

His face, normally expressionless, was set and grim. Yerik wove between the

suddenly stilled dancers, the old woman right on his heels.